Last Friday, I posted a not-so-serious note on how people think any new technology developed after their birth is worse than technology that was already around when they were born. But this touches on a serious subject that I want to address today and the next couple of Wednesdays: the lack of productivity growth in developed countries.

Here in the UK, we hear time and again about the ‘productivity puzzle’, i.e. why is the productivity of our workers lower than the productivity in comparable countries in Europe? And why is productivity growing at a slower pace than in other European countries? We don’t really know what the UK-specific reasons for that are, but I am not going to discuss this issue here.

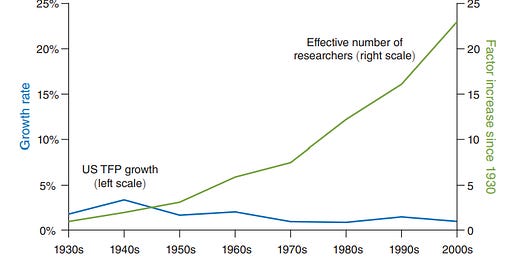

Instead, I want to discuss the ‘productivity puzzle’ in the sense of macroeconomists’ concept of productivity growth. What economists call ‘total factor productivity growth’ has not changed for decades despite us investing more and more into research, automatization and other forms of technological development. The problem is shown nicely in the chart below. Total factor productivity growth in the United States is compared there to the increase in the number of researchers since the 1930s. While the number of researchers has grown more than 20-fold, total factor productivity growth has remained remarkably stable.

US total factor productivity growth vs. growth in research

Source: Bloom et al. (2019)

For the uninitiated, total factor productivity (TFP) is a term that was coined in connection with Solow growth models. These models say there are two key ingredients to generate output: labour and capital. Any part of the growth in output that cannot be explained by changes in the labour inputs or changes in the invested capital is summarized as TFP growth. It is essentially a catch-all term for technological progress and innovation, but also rationalisation and automatization as well as plenty of other stuff we can’t really explain. For our purposes, I will just use the term TFP growth as shorthand for technological progress and innovation.

And the chart above puts the finger on an important issue that Nicholas Bloom and his collaborators pointed out some time ago. It seems that ideas are getting harder and harder to find. The result is that in all kinds of fields, progress is slowing down even though we put more resources at work. Just look at the years of life saved with new medication and treatments for cancer or heart disease shown below. The years of life saved by clinical trials for new treatments of heart disease has declined from 100 years per 100,000 people treated in 1970 to just 4 years per 100,000 people treated.

Research productivity in health care

Source: Bloom et al. (2019)

This trend is not just confined to health care. Similar trends can be seen in agriculture and technology where the famous Moore’s law is increasingly breaking down. Today it takes eighteen times more researchers to double the density of computer chips (and their computing power) than in the 1970s. Everywhere we look we have to invest more and more time and capital to get the same rate of progress as in the past. And since money doesn’t grow on trees and the ability of companies and governments to invest is getting more and more restrained, that does not bode well for future productivity growth.

Hence, over the coming couple of Wednesdays, I want to dive a little deeper into why research productivity is declining. Are scientists and engineers today just dumber than their predecessors? Surely that can’t be it.

Isn't it natural that it is getting more and more difficult to improve the better you get?

I’ve spent time both in academia and in industry and I believe I have some ideas on why. Through industrialization of research, pretty much any low hanging fruit in parts of science and engineering has already been picked. What is left is either intractable or too difficult (and sometimes there are physical limitations, such as in semiconductors). And those that can be solved, need significant time. These days, neither in industry nor in academia, there’s practically anyone willing to support that kind of research and in order to get a paycheck/tenure/promotion/funding you need to show steady and continuous progress. That leaves very little incentive for anyone to even try. Even worse, funding agencies like US National Science Foundation expect you to provide a path to the solution in your grant application. So you have to have already made some progress before you can even apply. Incentives and rewards matter