AI and automation provide few productivity gains: discuss

I know from experience how hard it is to write and publish an academic study, so forgive me for being mad at Daren Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo when I saw that these guys have finished three incredibly good papers on the economic impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI) at the same time. But then again, there is a reason why Acemoglu is considered one of the leading minds in economics today.

All three papers are in my view very important and should be read by everyone concerned with AI, robotics and related fields such as FinTech. In the first paper, the authors develop a model of how automation and new technologies change the demand for labour. The second paper focuses on the connections between an ageing society and automation. The authors show that as population ages, more and more automation will be used to replace middle-aged workers, aged between 21 and 55, increasing job insecurity and reducing wages for these people.

Finally, the third paper is more qualitative in nature and focuses on what kind of AI is the right kind of AI. Acemoglu and Restrepo argue that the optimistic view, that automation does not lead to a decline in labour since the jobs lost in one industry will be replaced by jobs in other, new industries, may be wrong. The classic example I use for this optimistic view of automation is that the number of bank tellers did not decline after the introduction of ATMs. Quite the opposite, the number of bank tellers grew, but their job description changed. Instead of taking in deposits and paying out withdrawals, bank tellers increasingly became “advisers” who helped their clients with a broad range of financial needs from savings to mortgages and investments.

The labour share in banking and other service industries could be held constant in the face of increasing automation because the services offered were expanded to new areas that required labour and were more productive than the automated areas. Arguably, the value add of a bank teller advising a client on a mortgage is significantly higher than the value add of a bank teller counting bills for an hour and handing them to customers.

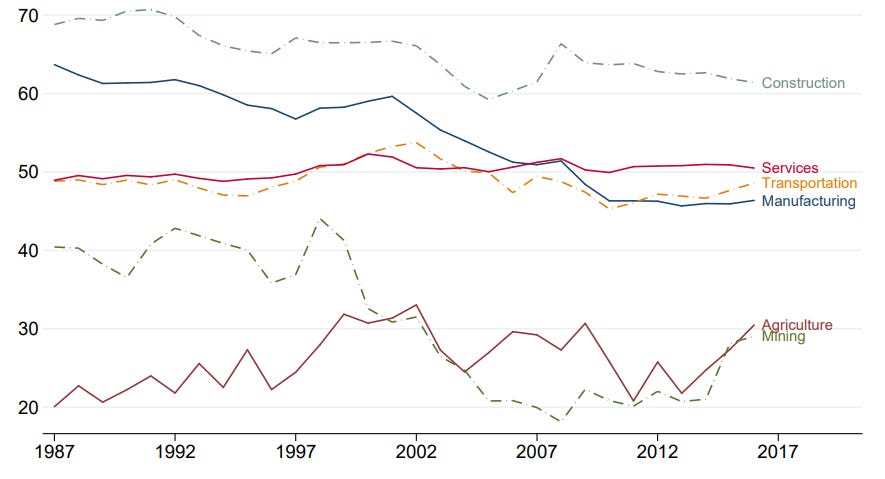

Compare this to the kind of automation we have seen in recent decades in the manufacturing industry, for example. A robot in a car factory is only minimally more productive than a human worker. The limited productivity gains are focused on less sick hours and a more consistent build quality, but the robot is neither faster than a human, nor does it produce better welding than a skilled worker. The reason why the professional welder has been replaced by the robot is simply that the robot is cheaper than the welder. Automation in manufacturing has reduced the demand for labour but it has not created sufficient productivity gains to create new jobs for the displaced workers in other areas (see chart at the bottom).

And this is the major problem with the current rise of AI and automation. It provides very few productivity gains. I have written in the past about how technological progress is slowing down exponentially in fields like semiconductor development and pharmaceutical drugs, and how businesses invest too little in research and development to even keep productivity growth at constant levels. For decades now, we have seen lower and lower productivity growth in the Western world while technology has increasingly replaced manual labour. Economists joke about how you can see the digital revolution everywhere but not in the productivity numbers, but if we all just sit back and think about how we go about our jobs today compared to twenty or thirty years ago (my apologies to the younger readers of this commentary) we will notice that we may have email, smartphones and a metric ton of data at our fingertips, but we are not getting much more done on any given day than in the past.

Acemoglu and Restrepo argue that this focus on AI to automatize existing tasks (e.g. industrial robots, self-driving cars, face and speech recognition) is dominant today because of market failures. Markets reward those activities that are immediately profitable or profitable within a reasonable time frame. Automation through AI fits the bill perfectly in this regard. But automation does not have to pay for the externalities that are created through it. Nobody asks Silicon Valley firms to help pay for unemployment benefits of displaced workers and nobody taxes robots and capital while labour is taxed more heavily and comes with all kinds of extra costs. Thus, they argue, application of AI that would enhance productivity dramatically is currently rarely funded by the private sector, which means that the current form of AI under development only intensifies the social frictions we have seen in recent decades. In order to overcome these failures, one might need to have more public investments in alternative forms of AI. In the past, governments have sponsored applied research programs that led to the invention of the internet and other forms of technology, but with the advent of austerity and higher scrutiny on government spending these sources of funding have diminished dramatically. And as always, if you invest less in your future, you should not be surprised if the future turns out worse than the past.

Labour share in the US 1987 - 2017

Source: Acemoglu and Restrepo (2019).