The financial literature is full of experiments on how people react to risky choices. But in the real world, we more commonly face ambiguity, rather than risk, and ambiguity is a little bit like risk on steroids.

A team from the University of Sydney gave 471 volunteers a series of decision tasks that are commonly used in both academia and as part of risk questionnaires by financial advisers to elicit risk aversion.

Here is the task they gave their volunteers:

No background uncertainty: You have $100 of income, which is guaranteed. It will neither increase nor decrease. You also have $100 in savings which you can invest…

Known risk on income: You have $100 of income, which can increase to $200 or decrease to $0. The probability of an increase and the probability of a decrease are known and both events are equally likely (50% chance). You also have $100 in savings which you can invest…

Unknown risk income: You have $100 of income, which can increase to $200 or decrease to $0. The chance of an increase or decrease is unknown. You also have $100 in savings which you can invest…

The instructions then proceed to ask each participant how much to invest in a risky investment. Note that the investment options always stayed the same. What changed was the degree of financial security of the participants. Either their income was stable and secure, or there was a background risk where the participants knew the probability of losing their job or getting a promotion. Or there was background ambiguity, where the participants knew they could lose their jobs but didn’t know how likely that was.

The background ambiguity version is much closer to what most of us experience in real life than the background risk version or the no income uncertainty condition.

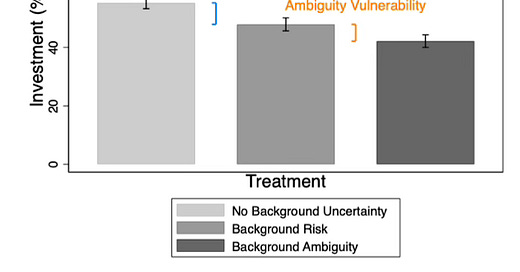

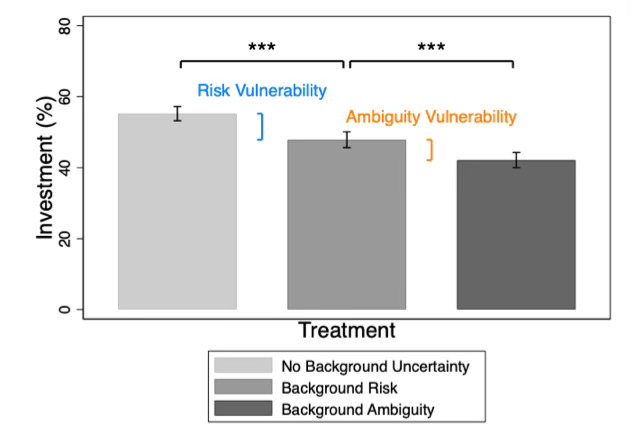

This is why it is worthwhile to look at the average amount invested shown in the chart below.

Investments by background risk condition

Source: Akbari et al. (2024)

When facing background risk on their future income, investors, on average, invested 6.3% less in risky assets than when their income was secure. But when facing unknown risks to their future income (background ambiguity) they invested 5.7% less than in the background risk condition and 10.7% less than when their income was secure.

In a second step, the researchers also asked about the stress their participants had in their lives and the source of this stress. They found that financial insecurity and job insecurity created the largest amount of stress, together with a close family member being unhealthy but ahead of the volunteer themself being unhealthy. And while ill health and other stressors did not translate into lower risk taking on the financial front, financial stress like a lack of job security and/or struggling to make ends meet had a significant impact on financial risk taking.

Translated into the real world, this study shows that if more people are in a financially precarious position (either because they are too insecure in their jobs or don’t have enough income for a decent living) the more they will stay away from investing in risky assets like stocks and instead remain invested in bonds and savings accounts. But as we know, this means that over time, these people can save less for their retirement and will struggle to make ends meet as pensioners. And so, the circle becomes a devilish feedback loop.

On a macro level, one can also speculate that in a country where people are facing systematically higher financial and job insecurity, the people are, on average, less likely to save. This widens the current account deficit of that country (the current account essentially indicates the savings preferences vs. investments of a country). I know, I am going out on a limb here and I am not going to point my fingers at specific countries with low job and financial security, but if you are running a country with a massive current account deficit, maybe one way to improve the current account deficit would be to increase financial security and reduce financial stress in your society, rather than engage in mercantilist economics.

I struggle to find a better argument for Universal Basic Income (goes into hiding). In Europe, that is.

Not only would it be a path to rolling a gazillion of benefit payments (unemployment, housing benefits, and the like) and even pensions into one simple system that would unlock a lot of untapped potential in civil service.

Even more importantly, the resulting removal of ambiguity might just be what’s needed to get more people to say ‘hell yes, now I’ll take the risk’ and go freelance, become an entrepreneur, create new businesses from the ideas they have but don’t dare implement – and create much needed dynamics and economic growth in the process.

I would be interested in your views with how this correlates with lottery spending - which is very high risk (expected returns below 0%) , but also far more common among poorer individuals (Below link suggesting poorest 1% of zip codes spend $600 (5% of paycheck) annually and the richest 1% spend $150 (0.15% of their paycheck))

Clearly it is a very different approach to "investing" - a 10% return on $600 is only $60 - perhaps the hope of life changing money is worth far more?

https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2024/04/02/the-economics-of-american-lotteries