I must sing the praises of David Blitz and the quant team at Robeco once again. I know it is getting boring but is it my fault that these guys keep on writing interesting and relevant research? This time, David asks if the equity risk premium is the same, and whether risk-free returns are high or low.

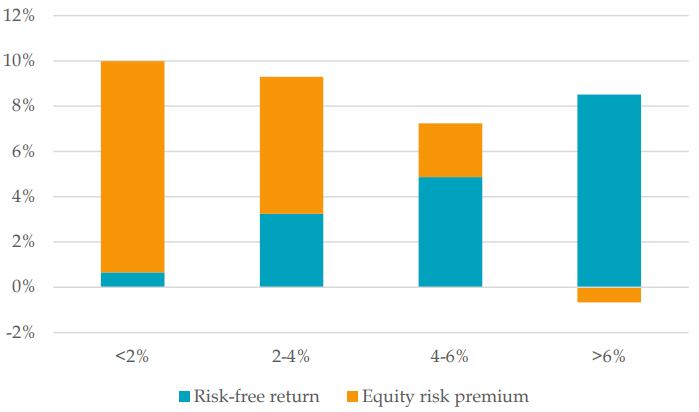

Conventional wisdom has it that the equity risk premium varies over time as sentiment and economic fundamentals change. But whether the risk-free rate is 1% or 5% shouldn’t make a difference, in theory. Emphasis on the words “in theory”. Looking at the historical return of equities in different markets from 1866 to 2021, Blitz finds that the equity risk premium gets bigger as the risk-free rate declines. The chart below shows the results for the US market.

Equity risk premium as a function of risk-free rates

Source: Blitz (2022)

The result of a high equity risk premium in a low interest rate world is not driven by the last decade alone. The equity risk premium was also high in previous periods of low risk-free rates. If the equity risk premium is higher in a low-interest-rate world it would be highly important since it means that equity market returns are not necessarily higher when interest rates are higher and not necessarily lower in a low-rates world. This in turn would mean that equities become relatively more attractive vs. other asset classes the lower the risk-free rates become.

We don’t know, yet, if this is a real effect, and I wouldn’t assume that it is, so proceed with caution here. David Blitz examines three different explanations for this effect qualitatively and finds no support for the equity risk premium as a true risk premium in the sense that it compensates for a higher risk of loss. The equity risk premium was negative during the 1930s and 1940s and very low to negative during the 1970s, arguably the periods when the risk of permanent loss of purchasing power was greatest for equities.

Similarly, there isn’t consistent evidence of the TINA (There Is No Alternative) explanation that says that lower interest rates make fixed income investments less attractive and push investors into higher return assets like equities. This may have happened last decade, but over the last century or so, there is no evidence that this effect really exists.

Which leaves us with the possible explanation that lower interest rates make it easier for companies to be profitable and to create systematically higher earnings growth. This explanation has some appeal since companies can lever up their balance sheets at low cost to increase earnings growth, but so far, we lack any systematic investigation into this and similar effects that could explain why equity returns above the risk-free rate may not be constant.

Hi mr.klement

Another simplifying way of looking at this is a higher risk free rate induces uncertainty very certainly like an Earnings drop. So if the P/E for the entire market or an individual stock is 50 when the risk free rate is low, the E will decline when the 10 yr bond yield moves up , P/E now becomes 75 or 100x assuming E declines by 25%, 50% brought on by the deflationary effect of the higher risk free rate

Very interesting Joachim. For teh benefit of us, do you have a position for Emerging Markets? We could use this analysis as a benchmark? Any insight?