If you read the job descriptions of equity analysts, you’d think the job consists of a lot of number crunching and analysis to come up with the best possible forecasts for a company’s future earnings and share price. But who are we kidding? In what is approximately the 1,000th installment of the long-running series “analysts are humans, too”, I want to show you how analysts really come up with their target prices for shares. Obviously, I cannot speak for any specific analyst, but thanks to Peter Clarkson and his colleagues, I can speak for the average analyst.

Clarkson analysed c. 1.3 million target price forecasts for US Stocks made between 1999 and 2018. The trick? He looked not only at fundamental factors like earnings growth forecasts but also at sentiment and psychological markets like the 52-week high of the share price.

The good news is that analyst forecasts of earnings growth in the next few years, as well as the long run, are linked to the target price forecast of the analyst. Short-term and long-term earnings forecasts by analysts can explain c. 25% of the differences in target price forecasts between analysts. However, the problem with target price forecasts is that they need to be anchored somehow.

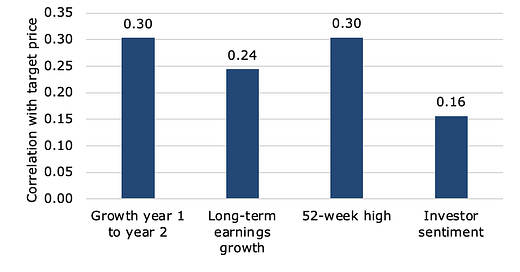

As everyone who has ever used a discounted cash flow model knows, you can make reasonable assumptions and come up with a large range of “sensible” target prices for a stock. It isn’t an exact science. So analysts need to anchor their forecasts and it seems they do it just like most retail investors do it as well. They look at recent share prices. The chart below shows that the correlation between the target price forecast and the 52-week high of a stock is about as high as the correlation between target price forecast and earnings growth forecasts from one year in the future to two years in the future. In fact, non-fundamental indicators like 52-week highs and investor sentiment explain almost as much in the variation of share price forecasts as fundamental indicators.

Correlation with target price forecasts

Source: Clarkson et al. (2020)

This anchoring based on recent share prices has implications for the usefulness of analyst forecasts. The study found that using the earnings forecasts alone creates target price forecasts that are predictive of future share price performance. However, the non-fundamental influences like 52-week highs distort the target price forecast. The higher the 52-week high of a stock relative to its own history or the more optimistic investor sentiment is, the more the target price will be subject to optimism bias. Higher past share prices anchor analysts to higher target prices and thus to less accurate forecasts since high share prices tend to be followed by lower performance and possibly falling share prices in the future.

Thus, the authors of the study found that analyst target price forecasts are pretty useful when share prices are low and investor sentiment is subdued, as is the case at the moment in the UK and Europe (but not in the United States). But as markets climb to increasing heights, analyst target prices become less and less useful as a predictor of future share price developments. You might want to keep that in mind the next time you hear an analyst talk about Tesla shares…

Sorry for the noob question ( I don't work in finance), when is a price forecast useful? When it is correct on the direction or when it is accurate? Or both? And by how much are the American price forecasts typically off? I imagine this is outside the scope of the paper but what about the Indian or Australian stock market, same things there?

Was there any breakdown between buy side and sell side analysts?