By now, I have been writing about the economic impact of the mafia in Italy so often, one could almost think I am obsessed with them. But it is the gift that keeps on giving.

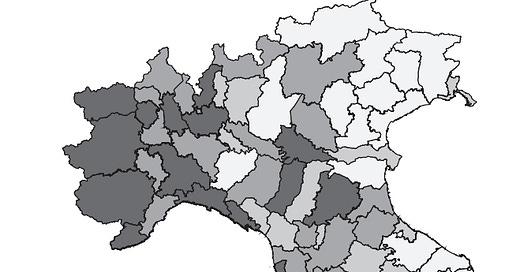

Consider a new paper by Litterio Mirenda and colleagues (hands down the best name I came across all year). There, the authors try to identify companies in north and central Italy that were possibly infiltrated by the ‘Ndrangheta, the Calabrian mafia. How do they do that? Well, the ‘Ndrangheta like all mafia organisations place a lot of emphasis on family memberships as a bond of trust. So, what the economists did was look at people with surnames that match prominent mafia families and that were born in Calabria but ended up as directors of companies in north and central Italy. And it turns out that in some areas, particularly in the big cities in the Northwest of the country, the share of mafia infiltrated companies can reach 2% as the map below indicates.

Potential share (in %) of companies infiltrated by the ‘Ndrangheta

Source: Mirenda et al. (2022)

Cross-referencing their estimates with data of company assets confiscated by the police for mafia involvement provides additional confidence that the methodology is likely to identify the correct companies. It turns out that the ‘Ndrangheta prefers to infiltrate mostly construction companies, followed by real estate and retail. However, as a share of all companies, mafia infiltration is highest in the utility sector and in financial services (e.g. money transfers). I guess my readers can figure out for themselves why one would focus on these sectors.

Once these companies have been identified, one can check how these companies differ relative to other companies in the region. And because the entry of directors that may be connected to the mafia is a matter of public record, one can also examine how the business activities of a potentially infiltrated company change over time.

The results are striking, but unfortunately not surprising. First, companies that are potentially infiltrated by the mafia are more likely to receive government contracts for construction, etc., and on average increase their revenues by 30% in the year after a mafia-linked director is appointed. However, the increased revenues of these companies do not translate into higher profitability or increased financial stability. Quite the opposite. Companies that are potentially infiltrated by the ‘Ndrangheta see their financial fortunes decline in the years after the infiltration.

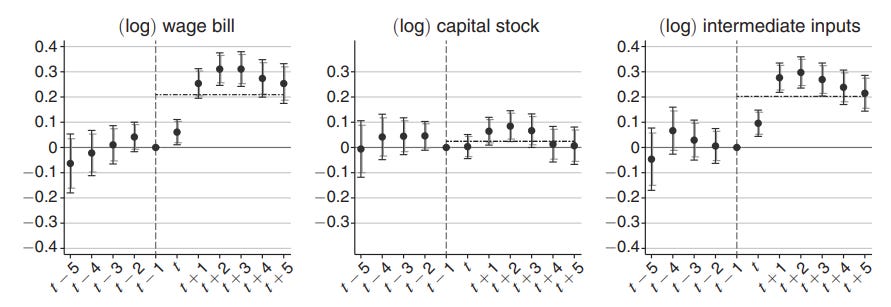

The reason is shown in the chart below. The cost of production for companies infiltrated by the mafia increases significantly. The wage bill increases by some 20% in the five years after the appointment of a potentially mafia-linked director (note, how careful I am in the choice of my words. You never know who reads these things…). Similarly, expenses for intermediate materials rise by 20% as well while the capital stock remains largely unchanged.

Costs for production inputs of mafia-infiltrated businesses

Source: Mirenda et al. (2022)

Effectively, companies that get infiltrated by the ‘Ndrangheta are being squeezed. They may get higher revenues by gaining market share and government contracts, but they have to buy materials from ‘authorised vendors’ and hire ‘selected personnel’ at above-market wages. The end result is that the companies that are potentially infiltrated by the ‘Ndrangheta are more likely to fail and go under. Not that anyone in the ‘Ndrangheta would care since they have made their money a long time before that happens…

Postscript: Don’t take this thought too seriously, but it occurred to me after finishing this article that leveraged buyouts (LBO) work pretty much the same way. A group of ‘investors’ buys a stake in a company, takes one or more seats on the board and starts levering up the company’s balance sheet to pay themselves large dividends. If the company succeeds, fine, but if it goes under, the general partners have long been paid back through dividends and interest payments. Seems like Bryan Burrough should have given his book “Barbarians at the Gate” a slightly different title.

and nationalizations of companies work pretty much the same way