One of the interesting changes in European stock markets since the pandemic is that European and UK companies are significantly increasing their share buybacks. This has all kinds of benefits since it reduces the tax burden for investors (compared to being paid a dividend) and increases EPS growth by reducing the number of shares among which net income is divided.

But I find it surprising how many investors take share buyback announcements as gospel. If a company announces a buyback programme of $1 billion, it will buy $1 billion of their shares, right?

Well, you see, there is a bit of a problem there. If a company announces a $1 billion dividend, shareholders will notice when the dividend doesn’t show up in their account. But when a company announces the same amount in buybacks and then doesn’t buy back shares, will anyone notice? After all, a buyback announcement is not legally binding.

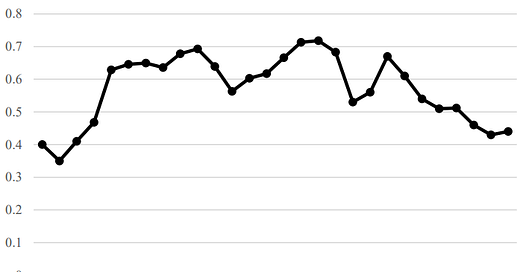

I recently came across the chart of the buyback completion rate in US companies below. On average, only 58% of the buyback amount announced by companies is really bought back afterward. I am pretty sure if I publish posts that are only 58% complete on average, people would complain. But in the case of share buybacks there is no public outrage, no media reports naming and shaming executives who overpromise and underdeliver. It’s almost as if investors don’t pay attention to what companies do after they announce a buyback programme.

Buyback completion rate among US firms

Source: Gupta et al. (2023)

Alas, it isn’t quite as bad. Konan Chan and his collaborators showed that on the day of the buyback announcement, share prices jumped by about the same amount regardless of the eventual outcome of the buyback. On average, share prices rise by 2% in reaction to an announced buyback programme.

But over time, there is an increasing difference in the performance of the share price of companies that buy back sha…

I would like to interrupt the current post to inform you that we now have reached 58% completion. Any information you gain from the rest of this article is thanks to me being more reliable than the average American corporate executive. Please send thank you notes to koi@jklement.com. Back to the post.

…res and companies that don’t follow through. Companies that do not complete their buyback programmes will face lower share price increases than companies that do and analysts will become increasingly negative in their assessment of a company’s shares. It’s almost as if analysts are at least to some degree paying attention.

But that attention has its limits. Even if a company doesn’t follow through on its buyback announcement at all, there is no negative consequence for the share price. Hence, from the perspective of a corporate executive announcing a buyback programme can be a simple way to talk up the share price for a while (preferably shortly before one’s options vest) without having to pay a price in the long run. No wonder then that narcissistic CEOs are more likely to announce share buybacks that never materialise. They are convinced that they can manipulate the market with their genius.

For investors, the lesson is clear, though. Don’t trust buyback announcements. What really matters is how much of its stock a company buys back in the open market. And should you be lucky enough to be a major institutional investor in a company, go check a company’s buyback completion rate before the next earnings call and ask the CEO and CFO in front of all the other investors and analysts why they didn’t follow through on their promises. I bet this will change their behaviour very quickly.

Brilliant observation. Buybacks might not be legally binding but perhaps if a company announces one it should be legally bound to announce that it has failed to action it.

Hahaha- love it. I did too- but never on these products I hasten to add.

We need to be careful of what we wish for. 100% completion rate does not necessarily equal the best outcome.

I think Lord Wolfson at Next knows what he is doing. Buybacks work when they generate a higher equivalent return on the capital than the company can generate by deploying it themselves. That rate is share price dependent.

Stay well