Could interest rate cuts lead to lower growth?

Tomorrow, the Fed is about to embark on its next rate cut cycle. And unlike in previous cycles, the Fed starts fighting economic weakness with much less ammunition than ever before. Typically, as the US economy has headed into recession, the Fed had to cut interest rates by 500bps to 600bps. Given the current starting point of the Fed Funds Rate that would take us down to -300bps, something that seems impossible to achieve without a run on cash.

Thus, if my expectation of a US economic slowdown, heading into recession in 2020 is correct, we are at the beginning of another interesting experiment in monetary policy: is it possible to stimulate real economic growth sufficiently when you start close to the zero lower bound? Or to put it in the terms used by Keynes: Can you push on a string and move the other end by doing so? Central banks might have a chance if they manage to implement a mechanism that effectively removes the zero lower bound on interest rates, but even then the effect on growth may be dampened significantly to the point where additional monetary stimulus might lead to lower long-term growth.

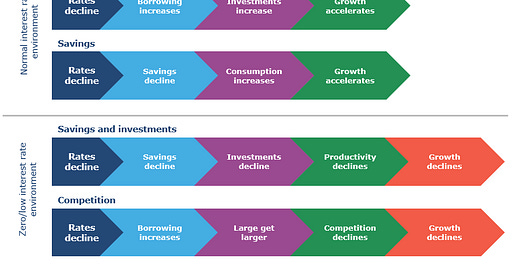

One of the risks of a zero or negative interest rate is a potential decline in private savings since savers are no longer rewarded with interest income. And because investments have to equal savings in an economy, the risk is that lower or even negative savings growth may lead to lower investment growth. As long as savings decline less than central bank balance sheets expand, there will be an increasing amount of “money” in the financial system available to be lent out to businesses and households for investment. In this situation, lending activity is essentially limited by the demand for loans, and not by its supply.

The situation changes, however, when savings growth becomes negative and savings decline faster than the central bank balance sheet expands. If households reduce their savings after a cut in interest rates or as long-term interest rates decline as a reaction to QE and other unconventional monetary policy measures, the supply of savings to finance loans to businesses and households can only grow if central bank assets increase and banks are willing to lend. If, however, an increase in central bank assets is insufficient to increase the supply of loans, for example if banks don’t want to lend because it is too expensive for them to do so, then the decrease in savings can overpower the growth in assets available for loans. In this case, an expansion of the monetary base could lead to a contraction in household savings and a decline in investments.

In the long run this should lead to declining productivity growth since technological progress is most often the result of investments in new technologies, as well as research and development. Declining investments and declining productivity growth then conspire to produce lower GDP growth in the long run as a consequence of lower interest rates and quantitative easing. In effect, more expansive monetary policy stimulates growth in the short run at the expense of lower growth in the long run. And that means that when the next recession is over, the recovery will be even more anaemic than the last one, limiting the Fed’s efforts to hike rates even more than during the last ten years.

Ernest Liu and his colleagues from Princeton University and the University of Chicago demonstrate another pathway for low interest rates to cause lower productivity growth. They show that in a low interest rate environment, a central bank that cuts interest rates triggers additional demand for loans by businesses. However, this additional demand is not evenly distributed across the economy. Large companies react quicker and expand their balance sheet at a faster rate than smaller companies. This is possible because larger companies have a bigger balance sheet to begin with and can thus provide more assets to banks as collateral.

This in turn means that the large companies in an industry can grow at a faster pace than the smaller companies. Because interest rates are at or close to zero, the cost of borrowing is minimal, and even in an economic slowdown, interest coverage remains high enough so that large companies do not face bankruptcy. Thus, large companies in an industry not only can grow faster than their smaller competitors, they can also survive longer even if they are less profitable than their smaller peers. This gives these market leaders the possibility to acquire the smaller competitors in the market (and since interest rates are close to zero the acquisition can easily be financed with new debt). Over time, market competition declines and the large businesses in a given industry become monopolies or oligopolies.

As market competition declines, productivity growth declines as well and the profit margins of the surviving large businesses increase, enabling them to service the existing debt more easily while reducing the need for future investments or productivity growth. In effect, in a zero interest rate world, Liu and his colleagues show how cutting interest rates may not only be ineffective to spur growth, but counterproductive. As interest rates decline, economic growth declines as well. Using data going back to 1980 in the US, they show that industry leaders indeed grew bigger as interest rates declined and the effect of outpacing their smaller competitors was statistically significant.

In summary, the expected rate cuts by the Fed may not be a blessing but a curse as they might prove ineffective to stimulate the real economy and avoid a recession in the US and at the same time might lower productivity growth and economic growth to levels below the ones we have seen in the last ten years.

Monetary policy effectiveness at normal and zero interest rates