Most market indices try to be as neutral as possible and follow strict rules wherever they can. But for every rule you define there are sometimes grey areas where one can interpret things one way or another or where two or more companies seem similarly suitable for index inclusion. That is why many indices have a discretionary component, i.e. a group of people that decides which companies will enter an index and which ones will drop out. Probably the most widely used market index with such a discretionary element is the S&P 500.

The most recent example of such a discretionary overlay on the S&P 500 was discussed widely in the market when Tesla wasn’t included in the S&P 500 in September 2020. The company had finally fulfilled the index requirement of having four profitable quarters in a row and investors expected the company to be included quickly. Yet, it was only in December 2020 that the stock finally became a part of the index.

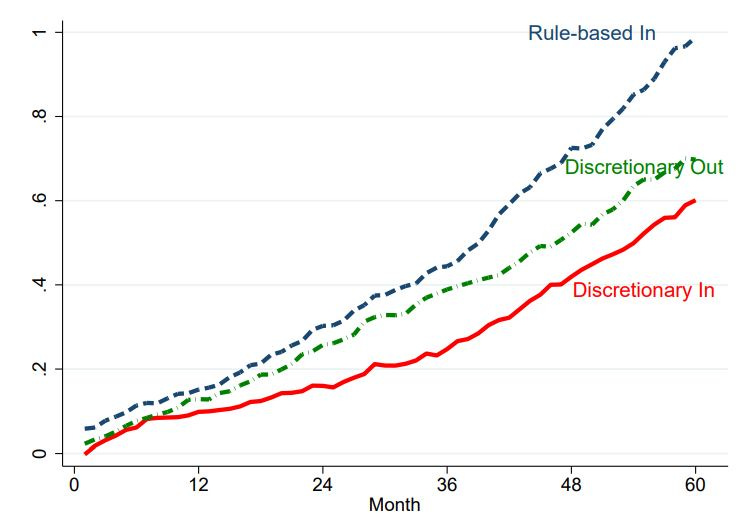

But why bother about three months here and there. It turns out that these kinds of small discretionary decisions add up over time. The chart below shows the cumulative performance of the stocks that would have entered the S&P 500 based on a purely rule-based approach to the S&P 500 vs. the stocks that actually made it in the index based on the existing discretionary approach. The chart also shows the stocks that dropped out of the index based on the discretionary approach. Because the discretionary decisions are substantially worse than a purely rule-based approach, investors who invest in funds tracking the S&P 500 have lost out on substantial amounts of money over time.

Impact of discretionary vs. rule-based inclusions into S&P 500

Source: Li et al. (2021)

But that’s not all. The authors of the study that produced the chart above also tried to figure out what determines if a stock is included in the S&P 500 in the discretionary approach. I will simply leave you with a quote from the conclusions of that note:

“Three data patterns suggest that the discretion is often exercised in a way that encourages firms to buy fee-based services from the S&P. First, a firm’s rating purchases from S&P tend to increase its likelihood of entering the index outside of the published selection rules (but purchases of ratings from Moody’s do not help). Second, firms tend to purchase more ratings from S&P when there is an opening in the index membership. This is especially true for firms ranked between 300 and 700 and at times when the payoff from being in the index are the highest. Third, a case study of a sudden rule change in 2002 that made foreign firms no longer eligible for S&P 500 index membership also confirms that firms’ purchase of S&P ratings is motivated, in part, by a belief that rating purchases affect S&P’s decisions on adding firms to the index.”

So interesting, however those that they keep in I wonder how many of those are just "value companies". Would need to look at the study to understand the data treatment but interesting stuff.

Would be interesting to read about the discretionary component of other indices,e.g: MSCI. And also: are there any ETFs in the market following purely "rule based indices" without this discretionary component? Any info on that?