Tomorrow, we get the inflation data for the month of May in the United States and I, for one, really hope we will see another decline in inflation. It seems likely that headline inflation will decline as the year drags on simply due to all the base effects I have discussed before. But core inflation may not drop by as much as higher energy prices filter through the system in the form of higher prices for all kinds of goods and wage inflation increases the costs of services.

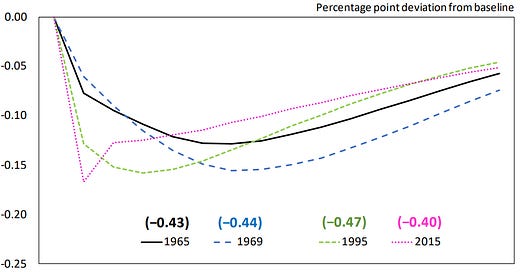

We are already having more and more discussions about a possible wage-price spiral, so it is timely that Jeremy Rudd from the Federal Reserve has compared the onset of high inflation in the late 1960s with the onset of high inflation today. Among other things, he focused on the impact of changes in unemployment on inflation. In his paper, he shows the difference in the reaction of core inflation to changes in employment in the 1960s vs today. The chart below shows the impact of a one percentage point increase in unemployment on unit labour costs. One can see that in 1965, before the onset of high inflation in the late 1960s and 1970s, a 1% increase in unemployment rates lead to a 0.43% decline in unit labour costs over the subsequent 8 quarters (i.e. 2 years for you and me). Similarly, a 1% decline in unemployment would have led to a 0.43% increase in unit labour costs over the following 8 quarters.

The overall impact of changes in unemployment on unit labour costs hasn’t changed much over the decades with 2015 pretty much the same as 1965. The only thing that has changed between 1965 and 2015 is that unit labour costs adjust back to normal much quicker as businesses can replace labour with technology or foreign labour more easily. In other words, wage inflation can be absorbed more quickly today compared to 50 years ago, but overall, the link between unemployment and wage inflation today is pretty much the same as it was in the 1960s.

Impact of 1 percentage point increase in unemployment on unit labour costs

Source: Rudd (2022)

But if we look at the link between wage inflation and core inflation, we see in the chart below that things have changed quite substantially. In 1965, five years before the onset of high inflation a 1% increase in unemployment rates triggered a 0.31% decline in core inflation over the following 2 years. In 1969 when the wage-price inflation took off, it was 0.35%. So, every percentage drop in unemployment rates created a 0.35% increase in core inflation. But today, as we head into the current period of high inflation, this wage-price spiral is much less effective. In 2015 a 1% drop in unemployment created just a 0.16% increase in core inflation.

Impact of 1 percentage point increase in unemployment on core inflation

Source: Rudd (2022)

This is a key difference between today and the onset of the high inflation period of the 1970s. Back in the 1960s before the inflation shock of the late 1960s and 1970s, there was a strong link between wage inflation and consumer price inflation. The wage-price spiral of the 1970s was not a regime change. The dynamics and links were already in place well before. Today, we go into the current inflation shock with a much weaker link between wages and prices. And so far, we have no evidence that this link has changed. Yes, there is a possibility that the link between wages and prices will re-emerge after being dormant for 30 years or so, but this seems unlikely at present. The people who argue for such a wage-price spiral have to provide evidence that there was such a regime change and I for one, cannot see any.

"The people who argue for such a wage-price spiral have to provide evidence that there was such a regime change and I for one, cannot see any." What evidence do "they" have to provide? Where can I find a list of people making this specific point? Charles Goodhart maybe but he would say it's more nuanced x10.