At the beginning of my career, I learned that when managing money, buying and selling in a portfolio is a tricky thing. On the one hand, it allows you to get rid of underperforming assets and buy into potentially better performing ones. On the other hand, it incurs costs that definitely reduce your performance.

For retail investors, we know that trading more frequently reduces their performance after fees. That has not changed in the age of Robinhood and other apps with zero or extremely low trading costs.

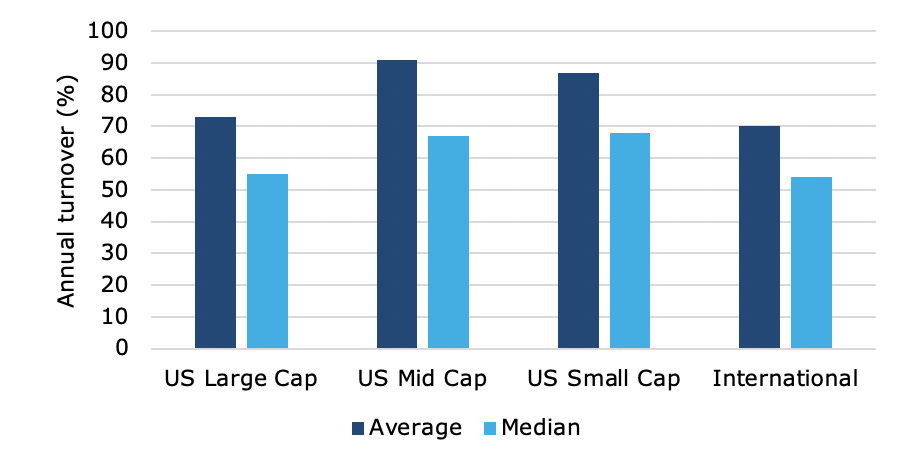

But for professional fund managers that may be different. Traditionally, fund managers had to contend with relatively high transaction costs which meant that if your portfolio turnover approached 100% or so, it became a serious drag on your performance. Today, mutual funds in the United States still have a median turnover somewhere between 50% and 70%. But the average turnover is higher, in the range of 70% to 90% which reflects that there is a long tail of high turnover funds.

Median and average turnover of mutual funds in the United States

Source: Hochachka (2021)

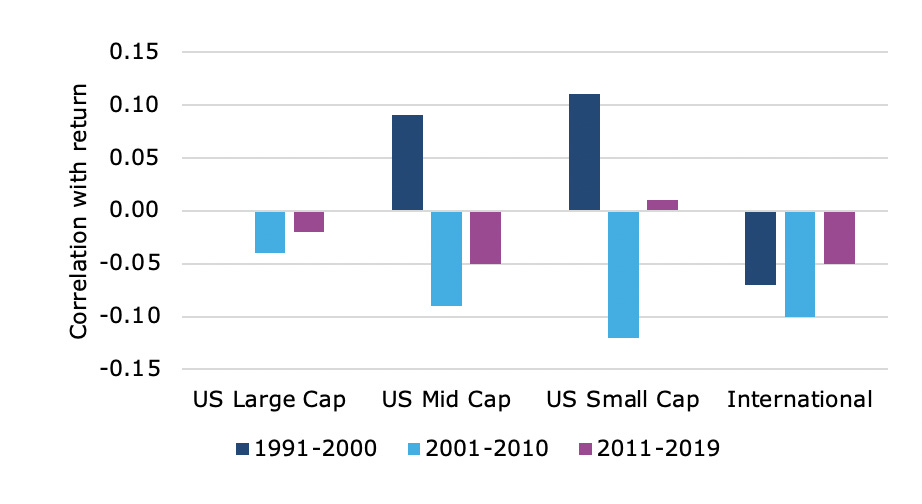

For professional fund managers, transaction costs have come down significantly as well and risk management tools have become more sophisticated and which may have reduced the relationship between portfolio turnover and fund returns. A study by Gene Hochachka from Frontier Financial looked into this and found that indeed, the relationship between fund turnover and fund returns is weak at best. Yes, there are individual funds with a strong link between portfolio turnover and fund returns and these outliers tend to influence the results of regression analysis. But if you look at it by classifying funds into groups from low to high turnover and then check whether they have low or high returns (thus giving individual outliers a lower weight) then the correlation between fund turnover and portfolio returns has virtually disappeared. Over the last three decades, it has fluctuated somewhere between -0.1 and +0.1.

Correlation between fund turnover and portfolio return in US mutual funds

Source: Hochachka (2021)

Does that mean that portfolio turnover doesn’t matter? Yes and no. Personally, I would still be hesitant to invest in a fund with 200% or even 300% annual turnover, not so much because I think the transaction costs would overwhelm the performance, but more because I think if your average holding period for a stock is some 4 to 6 months (which is what these turnover numbers imply) the manager is essentially chasing random noise in the market.

But as long as turnover is within reasonable limits, I think worrying about excessive portfolio turnover is not necessary. On the other end of the spectrum, I might again worry about fund managers with a portfolio turnover of 10% or less because that means they never change anything and really aren’t active in the sense of figuring out that sometimes a stock has run its course and needs to be replaced. Heck, even Warren Buffet’s portfolio turnover has from time to time reached 100%. While touting the benefits of buying good companies and holding on to them forever, he understands that a good company can sometimes turn into a bad company that doesn’t warrant an infinite time horizon anymore.

PS for my international readers: Here in the UK we have the next two days off to celebrate the platinum jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II. We will be back on Monday, 6 June 2022. In the meantime:

I'm not sure what has surprised me most in this post: that correlation between fund turnover and portfolio returns has virtually disappeared (I had heard of this but not looked at any data) or that Klement has a corgi (I had him down as an over-active collie dog person).

I am, as the kids say, shook.