Overconfidence is probably the most pervasive behavioural bias anywhere, though anchoring may give it a run for its money. And if you think you are not overconfident, then I encourage you to take the following quiz. Please answer these questions without googling the correct number. No cheating!

Below are ten general knowledge questions. Try to give a range so that you are 80% sure that the correct answer lies within the range.

What is the weight of a blue whale? Min: Max:

What year was the Mona Lisa painted? Min: Max:

How many independent states were there in 2000? Min: Max:

What is the distance from Paris to Sydney? Min: Max:

How many bones are there in the human body? Min: Max:

How many combatants were killed in World War I? Min: Max:

How many books were in the Library of Congress in 2000? Min: Max:

How long is the Amazon river? Min: Max:

How fast does the earth spin at the equator? Min: Max:

How many transistors were in a Pentium III chip? Min: Max:

If you are not overconfident, then 8 out of 10 of your answers should lie within the range you gave. Now go to the bottom of this post and look up the correct answers. Did you get 8 or more correct?

During my days in wealth management, I have travelled the world with this questionnaire and asked literally thousands of investors (both retail and professionals) to do this quiz. In all my years I only remember two people who got nine or ten answers right. And by the way, I got about five or six right when I did the quiz for the first time.

Obviously, knowing what the weight of a blue whale’s tongue is isn’t relevant for our investments but the point here is that these are all questions about topics where you feel you should be able to get a decent estimate if you think about the answer. Yet, in practice, what we think is a pretty good estimate, is in fact a narrow range that does not account for the full range of possible outcomes.

This, in turn, is highly relevant for investors and business executives alike. Fund managers and research analysts are constantly asked to estimate future earnings and while nobody knows the answer, we think by analysing trading activity, cost pressures, etc. of a company, we should be able to get a good idea in what range earnings should be. It is easy to show that earnings forecasts of analysts and fund managers are far too narrow to cover a realistic range of outcomes. I am not talking about extreme events like a global pandemic or a Russian invasion in Ukraine, but about relatively common occurrences like the possibility of a recession or the likelihood of having to discount a large part of one’s products to defend market share.

Similarly, corporate executives are also overconfident in their ability to forecast their own business or the success of a new investment project. If you want to dive into the inability of corporate executives to forecast what many investors think they know best, all you have to do is look at the annual CFO survey of Duke University and its results. I suggest you read this speech given by John Graham.

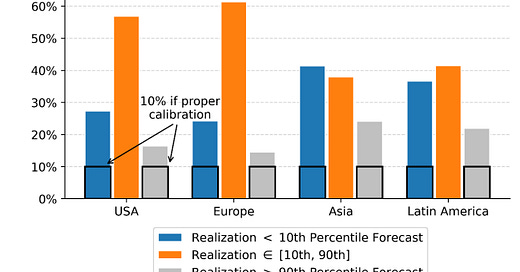

Here is a key result from the CFO surveys. If asked to give an 80% range for their revenue forecasts, far more than 20% of the time the realized revenues lie outside that range. And more often, revenues fall below the forecast range than exceed it.

Overconfidence in CFO forecasts

Source: Graham (2022)

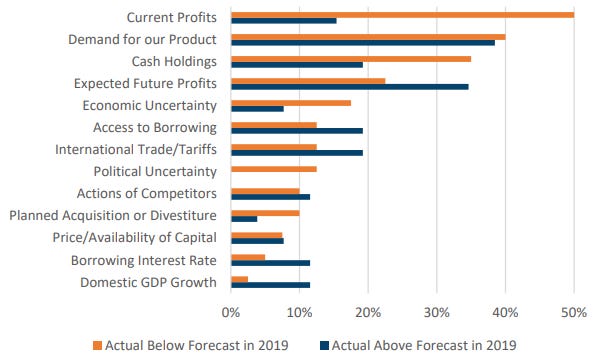

When asked why their forecasts were wrong, they cite overly optimistic forecasts of profits and demand for a company’s products as reasons. But not just that. Like most humans, CFOs and corporate executives have a tendency to blame markets or external circumstances for a failure to achieve targets and take credit for themselves when they meet or exceed their targets. That is a recipe for never learning to correctly calibrate your forecasts.

Reasons why forecasts were wrong

Source: Graham (2022)

My advice for corporate executives is to actively try to debias and fight your overconfidence and overoptimism. It is nothing to be ashamed of. I suffer from it just like everybody else does. But good executives have learned to implement internal checks on forecasts, like asking a colleague to be a devil’s advocate whose job it is to find all the flaws of a given project plan or forecast.

And similarly, since most of us reading this aren’t corporate executives, we investors need to be careful with our own forecasts and learn to be humbler in our forecasting exercises. Plus, and again no offense to corporate executives, as investors we should not take management forecasts and guidance as a starting point for our own estimates. If you do that, you are simply starting with a miscalibrated and overly optimistic anchor and it is really hard to get from that anchor to a more realistic unbiased forecast.

Answers to the overconfidence quiz:

About 125,000kg or 125 tonnes

1513

191

16,950km or 10,530 miles

206

About 8.3 million

About 18 million

About 6,250km or 3,884 miles

1,700km/h or 1,056mph

9.5 million

Great blog! Are the CFO's forecasts generally in line with corporate guidances? After all, corporate guidance is less often over-optimistic.