If you work in the financial industry, you are used to working long hours. Particularly in investment banking, working long hours seems a badge of honour, though I always wonder if working long hours creates that much more output.

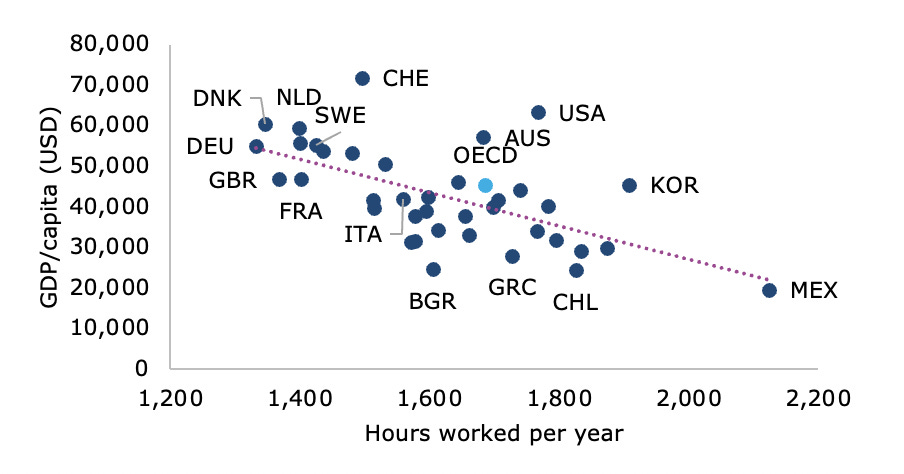

Hard for me to say since I don’t work in investment banking, but there is at least a possibility to check the relationship between hours worked and output generated across countries using macroeconomics. The chart below shows the GDP per capita in 2020 for a set of high- and middle-income countries. GDP per capita is used here as the national income per person in different countries. I put this in contrast with the average number of hours worked per person in a year. I removed commodity-rich countries like Saudi Arabia or Norway because their GDP per capita is heavily distorted by the revenues from commodity exports (though I did leave Australia in the chart).

GDP/capita vs hours worked

Source: OECD

Middle income countries like Mexico or Chile have lower GDP per capita but work more hours per year. That is a reflection of lower wages in these countries and these countries specialising in lower value-add manufacturing rather than high-tech manufacturing and services.

But if we look at high-income countries, there are interesting differences and notably, there is no correlation between hours worked and output generated. In the United States, people work many more hours per year than in Switzerland (country code CHE), the Netherlands (NLD) or Denmark (DNK), yet GDP per capita is roughly the same. If we look at the large European economies, we notice that Germans work the fewest hours in our sample, yet their GDP per capita is about 20% higher than that of France or the UK, where people work 50 to 80 hours more each year. And then there are the cases of Italy and Greece (GRC) where people work many hours per year but their GDP per capita is low and sometimes much lower than that of the UK or France.

Economists usually express labour productivity as GDP per hour worked which is calculated as the total GDP divided by the number of hours worked per full-time worker multiplied by the number of people employed in a country. But labour market participation is different from country to country and depends on the available social safety net and the ability of people to earn enough money so one parent can stay at home and take care of children or other relatives. Put simply, productive people can afford to work less or have family members stay at home. They don’t need a second income.

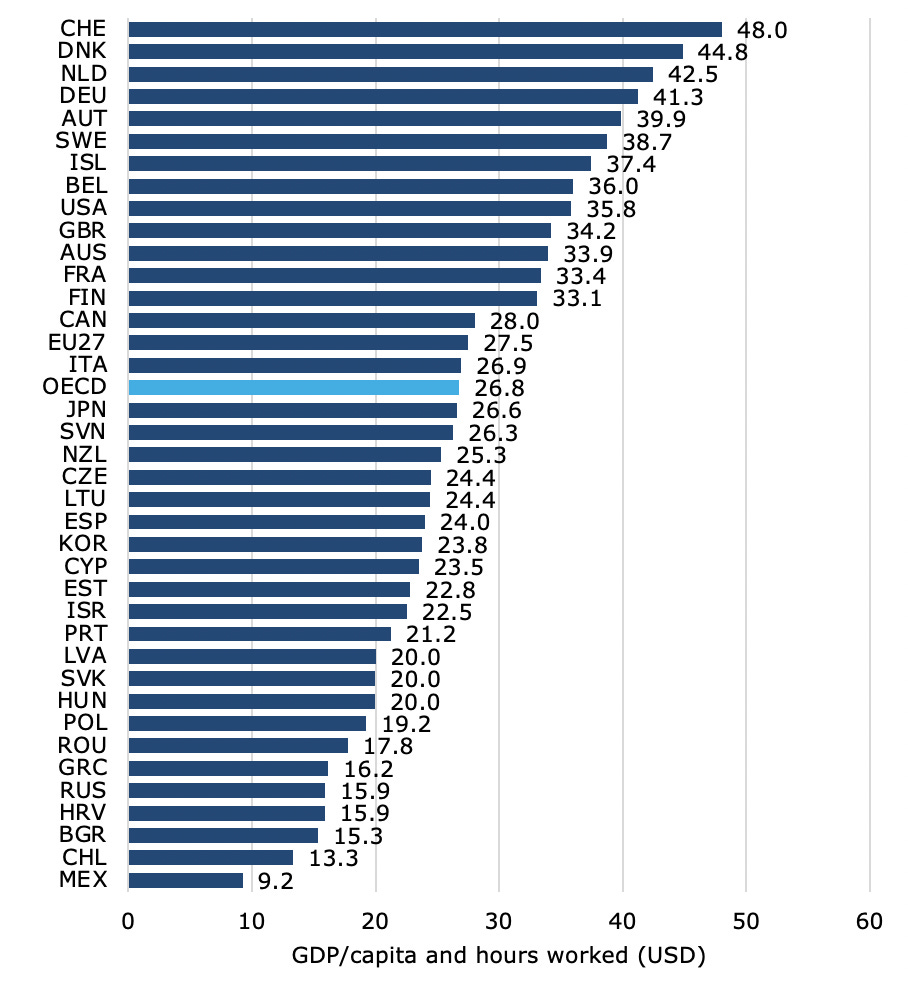

Thus, my favourite productivity measure is not GDP per hour worked but GDP per capita per hour worked. That is, I leave labour market participation rates out of the equation and calculate the income generated by every person, employed or not per hour worked. The chart below shows the comparison of this national average productivity for the whole set of countries.

GDP per capita and hours worked

Source: OECD

Notice how the United States, Australia, the UK, and France have almost identical productivity rates but work very different hours per year. Effectively, what this shows is that in France and the UK, people have traded some of their national income for more leisure time. If they would work as many hours per year as Americans did, they could achieve a similar GDP per capita.

But neither Americans nor Brits are particularly productive. The champions when it comes to productivity are the Swiss, together with the Dutch, the Danish and the Germans. I don’t mean this to be racist, but there is something about Germanic cultures that makes them incredibly productive. And the main benefit of this higher productivity is that these people can work really short hours each year and still create more income than Brits of French people or about the same income as the Americans.

So as you embark on a new year, maybe think about your work a bit more. They say people should work smarter not harder. If you become more productive at work (read: if you become a bit more German), you can go home earlier each day and spend more time with your family. And we know that spending time with family and friends makes people happier. Spending longer hours in the office doesn’t. Increasing your productivity at work has enormous benefits for your work-life balance and your personal happiness.

But make sure you don’t overdo it. I recently came across an article in Germany about a Professor who was so obsessed with making her life and work more efficient and productive that it made her sick. The quest for efficiency became a form of OCD. I guess that is a particularly German problem, though.

There is on final step missing: factoring in the cost of living. Switzerland is (from my German point of view) much more expensive than Germany and that may even out the higher GDP/capita and hours.

You have great courage to draw attention to the virtue of die protestantische Arbeitsmoral. It is considered a vice, unfortunately, in much of American academia. I do admit, however, that my best days as a manager involved toning down my Prussian instincts!