Forward guidance does not influence inflation expectations: discuss

Forward guidance by central banks has become the main policy tool to influence inflation expectations of investors, businesses and households. Many economists think that central bankers are doing an excellent job with their forward guidance since inflation expectations as measured by the inflation expectation of households in the University of Michigan Consumer Survey of breakeven inflation rates of government bonds are incredibly stable. The levels may be different as the chart below shows, but since the adoption of forward guidance by the Federal Reserve in the early 2000s, inflation expectations have become increasingly stable – especially after the financial crisis of 2008 when forward guidance and quantitative easing became the two dominant tools for monetary policy.

Inflation expectations by consumers and bond markets

Source: FRED St. Louis Fed.

But has anyone cared to ask if forward guidance has the power to influence inflation expectations of consumers in the first place? The problem is that in order to understand how forward guidance influences inflation, you need to have a more than basic understanding of what a central bank does and how its actions influence inflation. You need to understand that by lowering interest rates, a central bank wants to make loans cheaper and incentivise people to borrow money. This borrowed money should then be used for investments and consumption which in turn should make things more expensive because demand increases while supply remains largely unchanged.

In essence, people need to understand that central banks determine the basic level of interest of which all loans are priced. They then need to understand that lower interest rates make loans cheaper. They then need to understand that cheaper loans mean that people save less and spend more. And finally, they have to understand how demand and supply works and figure out that if there is more money chasing the same amount of goods, they will get more expensive.

Do you think your mother understands all of this? I know my mother doesn’t. All she understands is what things cost if she goes shopping in her local supermarket.

And this is what Francesco D’Acunto, Daniel Hoang and Michael Weber have shown in a series of papers. First, they demonstrated that people with a below average IQ are less able to forecast inflation and do not really understand how inflation works. Then, they showed that the price anchor for inflation expectations for most households, and in particular those with lower cognitive abilities (and presumable lower levels of financial literacy) are predominantly driven by the prices for goods in grocery stores rather than a representative basket of goods and services they consume.

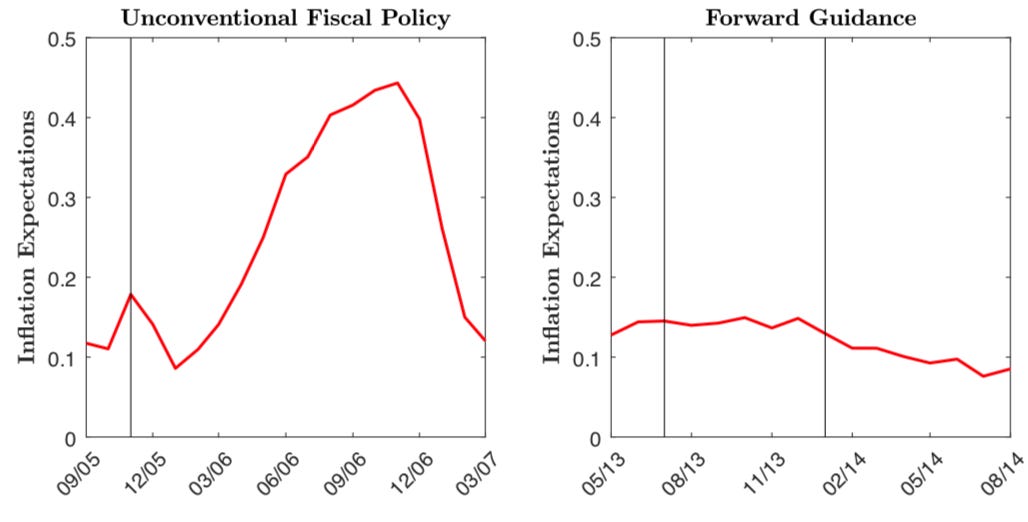

And finally, they showed in the case of Germany that forward guidance is largely ineffective. Take a look at the inflation expectations of German households around the time of an unexpected tax hike. In November 2005 the German government was forced to hike VAT in order to reduce its deficit and stay within the limits of the Maastricht Treaty – limits that the country had violated in 2003 and 2004. The VAT hike was scheduled to take effect in 2007 and the left-hand chart below shows how this surprise tax hike significantly influenced inflation expectations of German households well before the tax hike came into effect. The share of households that expected higher inflation due to the tax hike rose from 10% to 45%.

Inflation expectations of German households

Source: D’Acunto et al. (2019).

Compare this to the expectations of households after the European Central Bank (ECB) adopted forward guidance in 2013 and 2014 (right-hand chart above). There was virtually no change in the percentage of households who expected inflation to rise after the adoption of forward guidance. In fact, the percentage of households that expected inflation to increase continued to decline throughout these two years.

As I say in my Ten Rules of Forecasting: for behavioural change to happen, the event must be salient, the outcome must be certain and the solution must be simple. Similarly, for people to understand policies and their impact on households, the policies must be salient, the outcome must be certain, and the mechanism must be simple.

Forward guidance fails on at least two counts. It is not salient because who outside the world of professional investors reads policy statements of the ECB? Second, it is not simple because the actions of the ECB are many steps removed from the shopping experience of everyday people. And because of these two deficits in the effectiveness of forward guidance, the outcome is anything but certain. Tax hikes, on the other hand, especially when they are focused on consumption and income taxes, are highly salient. The outcome is certain (you have to pay more for things, or you get less money at the end of the month) and their impact on your life is really simple: you’re screwed.

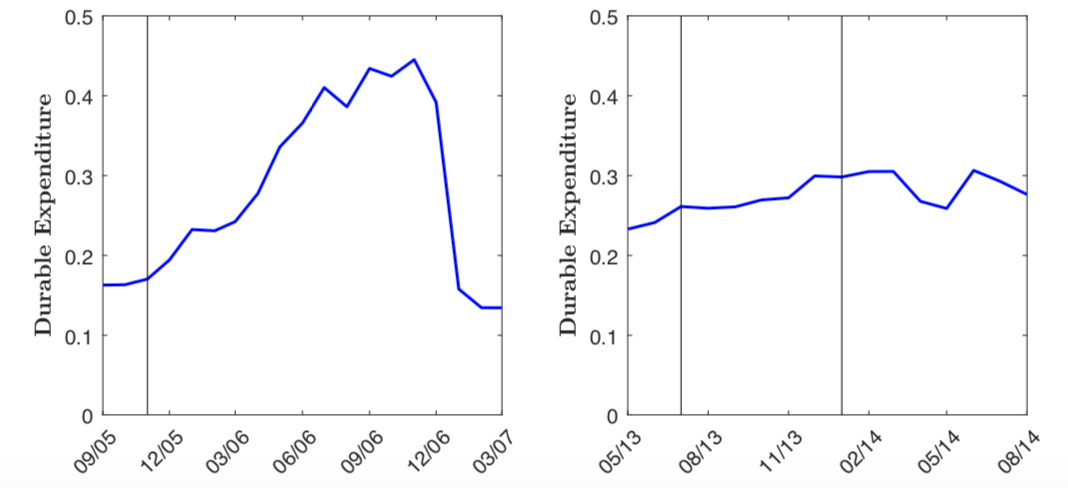

And because people tend to understand the impact of fiscal policy measures much better than the impact of monetary policy measures, they change their behaviour accordingly. In reaction to the VAT hike in Germany in 2007, many households started to buy more durable consumer goods, while the reaction to the introduction of forward guidance was a shrug of the shoulders. The ECB did not manage to induce anyone to consume more – and I am pretty convinced that the Fed does not induce anyone in the US to consume more by lowering its policy rates.

As I have argued before, I think we have reached a point where monetary policy has become completely ineffective and it is just a matter of time until markets will find out that the emperor has no clothes.

Consumption of durable goods of German households

Source: D’Acunto et al. (2019).