It’s funny how perceptions change. Throughout most of my career, which admittedly only spans about 25 years, one persistent narrative about stocks was that they are a good inflation hedge. The assumption was that because stocks represent real assets, share prices rise if inflation increases. I have been talking a lot about the possible comeback of inflation in 2025 over the last twelve months and the reaction by equity investors today is the complete opposite. They are very much afraid of rising inflation.

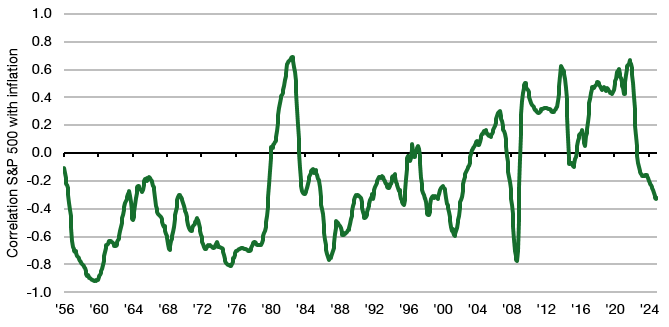

I always emphasise that there is no hard and fast rule for the correlation between stocks and inflation. It very much depends on what kind of inflation you get. The chart below shows the rolling 5-year correlation between the S&P 500 and US headline inflation. If stocks are an inflation hedge, you would expect the correlation to be positive and hopefully as close to 1.0 as possible.

Rolling 5-year correlation between the S&P 500 and inflation

Source: Panmure Liberum, Bloomberg

Note how for most of the last 70 years, the correlation has been negative and not just a little. Stocks are decidedly NOT an inflation hedge. But throughout my career since the turn of the century, the correlation has been mostly positive. For about two decades, stocks acted as if they were a mild inflation hedge.

What’s the difference between these two regimes? Diego Bonelli, Berardino Palazzo, and Ram Yamarthy show nicely that it depends on whether incoming inflation is perceived as good or bad by the market. If the market perceives inflation as good, share prices rise in response to higher inflation. If the market perceives inflation as bad, share prices drop.

This begs the question when do markets perceive inflation as good or bad?

In short, it boils down to the source of inflation. If inflation is demand-driven, it reflects stronger growth and hence stronger earnings growth for businesses. Yes, it might trigger rate hikes by the Fed to fight inflation, but that prospect is offset by the improved outlook for company profits.

If, on the other hand, inflation is supply driven, because there is a shortage of commodities like oil or a shortage of labour, then it is perceived as bad inflation because any rate hikes by the Fed are not going to be offset by stronger earnings growth. Indeed, supply-driven inflation may do the opposite and reduce earnings growth because companies face higher costs from higher oil prices, for example.

If you look at the chart above, you will notice that in the 1970s we had major supply disruptions for oil, which triggered supply-driven inflation and tanked stock markets. The same happened in 2022. But between 2008 and 2022, we didn’t have any such supply shock. Instead, the only source of inflation we had was demand-driven inflation from a fast-growing and possibly overheating economy. No wonder then that many investors believed until 2022 that stocks are a good inflation hedge. They had no first-hand experience of supply-driven inflation shocks.

Today, we face a rather weird situation in the US where inflation is driven by supply-side effects and demand-side effects to a similar degree, as the excellent data by the San Francisco Fed below shows. In the chart, I have left out a third component of inflation which can neither be attributed to supply or demand but is ambiguous. But the fact is that we have to monitor the situation to see if inflation is rising and due to which factors.

Contribution of demand and supply effects to inflation

Source: San Francisco Fed

Suppose I buy an apartment building in 2009 for $1 million. In 2022, after many years of QE and ZIRP, and no real economic growth, the building is worth $2 million. This is asset inflation. At some point, the rents have to increase (which is counted as price inflation). This is probably caused by price inflation, which causes wage inflation, which allows me to raise the rent (my tenants have more money!).

Of course, this is an oversimplified example, but it illustrates the point: asset inflation causes price inflation with a long and variable lag. We have had major asset inflation since the 1980s, which has caused price inflation along the way.

I claim that price inflation is weakly coupled with stock prices, but asset inflation is strongly coupled.

Cheers!

If I understood your post correctly, tariff-driven inflation is bad because it increases costs for consumers and businesses without boosting economic growth or corporate earnings.

The next question is whether the Federal Reserve would reduce interest rates to offset this inflation. If they don’t, inflation could rise significantly higher. However, we might still be in a recession even with an interest rate reduction.

What tools would the Federal Reserve have to pull the economy out of such a recession? If the tariff situation lasts only a few months, it may or may not result in a mild recession. However, if tariffs continue for the rest of the year or beyond, then we may see a recession, which could deepen depending on who continues to be a target of tariffs and how those countries retaliate.

The administration might push for interest rate cuts even before a mild recession occurs, especially if inflation rises above 3%, to argue that tariffs benefit the country. Falling gas prices could provide some relief and are already used by certain parts of the media as a benefit of tariffs, as they indirectly help both consumers and businesses, but it may not be enough to offset the broader inflationary pressures caused by tariffs.