Today’s post was hard for me to write because I have to indirectly admit that I am probably not as smart and knowledgeable as I think I am. But dealing with cognitive dissonance is part of becoming a better investor, so here we go.

Last Friday, I talked about how I was trained at university not to memorise facts but memorise how to find the facts and information I need to solve a given problem. The problem is that if you are focusing your efforts more on how to find the right information you spend less energy on remembering the information. People who knew that certain information was easily available via a Google search would remember less of the content but better remember how to Google it.

And this person would be me. I love Google or rather Google Scholar. In my work, I use Google Scholar far more often than regular Google (I estimate about 80% of my searches at work are done via Google Scholar). By using Google Scholar, I know I automatically get rid of “analyses” by the marketing departments of investment firms which are often distorted by economic incentives and can focus on the highest quality research usually produced by academics.

But while I was reading the research on accessibility of information, I came across a paper by Matthew Fisher and Daniel Oppenheimer referenced there. They asked volunteers to participate in general knowledge quizzes about the capitals of countries (e.g. what is the capital of the United States, Kenya, or Burundi?) or identify the companies behind certain logos like the Nike swoosh or the Guinness harp.

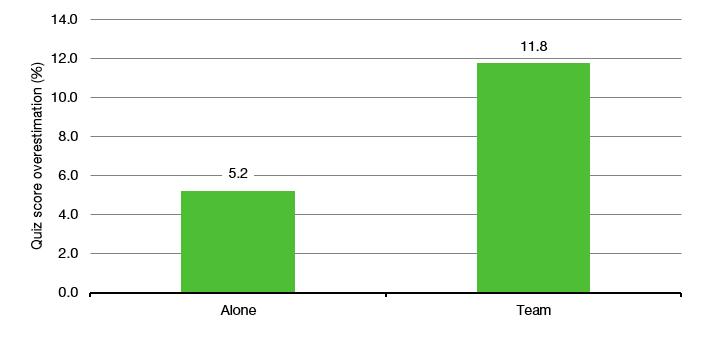

In a series of experiments, they let participants answer these questions on their own, without any help or with the help of other humans or robot assistants. The trick of the experiments was to ask the participants how well they would do before the test and then compare their actual test results with their estimates. As I have explained here, we all are overconfident about our abilities and our knowledge. But what is fascinating about the studies of Fisher and Oppenheimer is that our overconfidence increases, if we have access to outside help. Yes, working in a team enabled volunteers to get more answers correct, but while the expected improvement was large, the actual improvement was very small. Looking at different versions of the outside help, it became clear that this increase in overconfidence did not depend on whether the volunteer had outside help from other volunteers or machines, or whether the outside help was correct or not. The mere fact that the volunteer had access to more resources made her more overconfident.

Overconfidence increases if we have access to outside help

Source: Fisher and Oppenheimer (2021)

As I said, I love to use Google in order to find information and I tend to think of myself as very knowledgeable. In fact, I tend to think of myself as more knowledgeable than most people. But this research indicates that I am suffering from the illusion of knowledge created by my ready access to the vast knowledge of Google. In truth, I might know quite a bit less than I think I know. And this realisation creates cognitive dissonance. It’s not a nice feeling but overcoming it and reconciling your self-image with reality is a key success factor in becoming a better investor. I know this because I just googled it…

"I know that I know nothing"- Socrates