Has 2022 made investors shy away from stocks?

Yesterday, I ended my thoughts on the question if households have increased their equity investments as a hedge against inflation. Some households may even have made their first equity investments in the search of higher returns that can compensate for inflation. But if some investors have come into the market recently, their experience with stock markets would have been anything but good. Does that mean they will sell equities and shy away from the asset class in the future?

This is where a series of lab experiments performed by researchers from UC Santa Barbara can help us understand how investors react to their first steps in equity markets. The experiments were deceptively simple. The researchers asked a bunch of students to decide which one of six ‘lotteries’ they wanted to play. The first lottery was a safe investment that paid out 28 points, each point worth $0.15 for a total profit of $4.20. The next five lotteries were increasingly risky but also came with increasing expected payouts ranging from $4.50 to $10.80.

The participants were asked which one of the lotteries they wanted to play. Then they would roll two dice and if they rolled an even number, they would earn the higher of two outcomes, if they rolled an uneven number, they would earn the lower of two outcomes (i.e. a 50/50 chance for higher or lower returns).

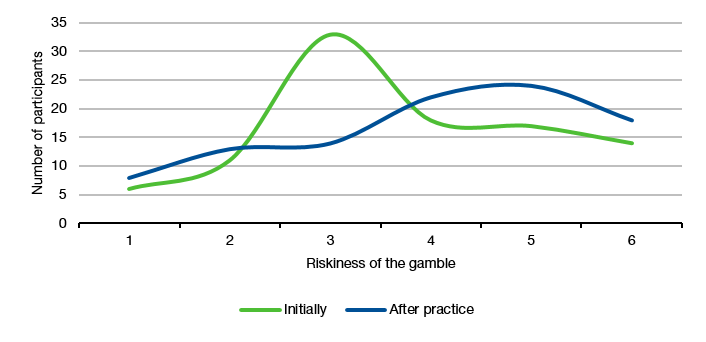

After the participants made their original choice, they got to practice the game for 24 rounds and then were asked to make the same choice of lottery again. The chart below shows how many participants chose each lottery at the beginning and after 24 rounds of practice with the game.

Risk aversion before and after practice with a lottery game

Source: Charness et al. (2022)

Interestingly, as participants became more familiar with the risk-return trade-off, they became more willing to accept additional risks if it was compensated with higher returns. In essence, most people became more comfortable with financial risk as their experience grew. The effect was stronger for women than men indicating that women build more confidence in their investment decisions as they gain more experience.

But here is the interesting thing. The lottery game never created any losses. All options in the game provided positive returns, just some returns were higher than others. To assess whether participants who incurred losses would stay away from risky lotteries one has to look a little bit deeper. And whether the participants had a lucky hand in selecting lotteries or not didn’t make much of a difference. Even the participants who experienced more negative outcomes in their practice rounds were on average switching to a riskier lottery after practicing.

This result flies somewhat in the face of loss aversion or risk aversion theory and certainly is the opposite of the snake bite effect documented in behavioural finance. The researchers examine why there may be no snake bite effect in their experiment and the answer seems to be that investors in their experiments were quite hands on and involved with their investments. This immersion in their investments created a stronger learning curve that eliminated the snake bite effect. In other words, the more front and centre the outcomes of your investment decisions are, the faster you learn. And that makes me confident that the poor returns of 2022 so far have not created a group of new equity investors that shy away from the asset class forever because of their short-term losses.