The Phillips Curve, the famous observation in the 1960s and 1970s that there is a trade-off between inflation and unemployment, has been declared dead after the financial crisis. Traditionally, one would expect an economy with lower unemployment rates (i.e. higher employment) to face higher inflation due to increased demand, while bringing down inflation creates an increase in unemployment.

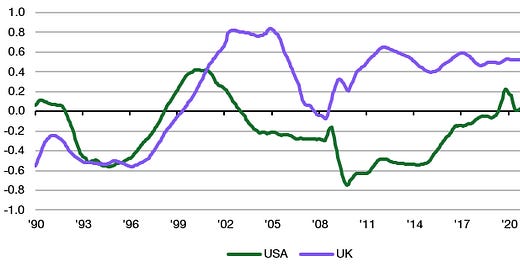

The simplest way (and arguably overly simplified way) to look at the Phillips Curve is to plot the 10-year correlation between unemployment rates and inflation as I have done below. If the Phillips Curve holds, one would expect to see a significant negative correlation (somewhere below -0.4). Yet, for the last two decades, this correlation has been close to zero or even positive.

10-year correlation between unemployment and inflation

Source: Liberum, Bloomberg

However, note how in recent years the correlation has again become significantly negative. Does that mean the Phillips Curve has risen from the dead and is now steep enough again to be useful for policymakers?

If you ask Anil Ari and his colleagues at the IMF, the Phillips Curve has indeed become steeper, due to two effects.

First, there is the effect of lower trade intensity, otherwise known as deglobalisation. In essence, if the economy of a country becomes more globalised, it opens itself up to foreign labour and the link between inflation and unemployment becomes weaker. Meanwhile, if a country removes its trade links, it has to rely more on domestic labour and the link between inflation and local employment rates becomes stronger.

Second, there is the effect of digitalisation. If an economy becomes more digitalised, businesses can react more flexibly and replace workers with machines. Hence prices become more flexible, and you have bigger changes in inflation in response to a small change in employment (i.e. consumer demand). As a result, increased digitalisation should lead to a steeper Phillips Curve.

The chart below from their publication shows the estimates of how the Phillips Curves in different countries have shifted relative to the 2012-2019 average. We can see that rising digitalisation in the aftermath of the pandemic has made prices more flexible and hence created a steeper Phillips Curve. Meanwhile, trade intensity has continued to increase a little bit creating a somewhat flatter Phillips Curve. The net effect is a slightly steeper Phillips Curve in the post-pandemic world where a one percentage point increase in the output gap creates about 0.5% higher inflation rates in the eurozone and 1% higher inflation rates in the UK.

Change in Phillips Curve steepness

Source: Ari et al. (2023)

That is substantial but not excessive. And the steepness of the Phillips Curve is still not high enough, in my opinion, to make this theory useful for policymakers. In fact, given the decline in inflation at the moment with a very robust job market, I wonder if the Phillips Curve isn’t flattening again as I write this, and we are on our way back to the typical picture of the last twenty years of a flat Phillips Curve.

Scott Sumner makes a very compelling case that the correct Phillips curve is the relationship between wage inflation and unemployment

https://www.econlib.org/the-actual-phillips-curve/