Healthy, wealthy, and wise

If you are working as a financial planner or advising private clients, you know that that there are two interrelated systematic problems in their behaviours. First, most people tend to save too little for their retirement and old age and consume too much. Second, most people tend to live longer than they think they will. The combination of these two biases means that far more investors run out of money at old age than need be and many face old age poverty.

Unfortunately, we no longer live in the age of almshouses, and even if we did, hardly anyone would want to live in an underfunded asylum for poor people. It is simply degrading.

A new study by researchers from the University of Glasgow sheds light on how these two biases reinforce each other and which investors are particularly prone to fall into this trap. Based on the US Household Survey, an annual large survey of US households eliciting their beliefs about all kinds of economic and social conditions and outcomes, they compared how long someone who is 50 years old thinks he (or she) is going to live and compared the results with the actual survival rates from statistical tables. Below, you can see the results for people aged 50 who were asked what the probability of living to age 75, 80, or 85 is (left hand side of each chart) and for people aged 75, 80, and 85 who were asked what the probability is that they live another 15 years. The black lines show the true probability of living to that age as time passes and people turn from 55, 60, 65, etc. The blue lines show the subjective estimates of what the likelihood of survival to this age is. The charts may look complicated, but the difference between the black lines and the blue areas show that younger people (aged 50 to 70), drastically underestimate how likely it is for them to live to old age. Meanwhile, older people (age 75 and over) overestimate the likelihood that they will live another 15 years.

Subjective vs. objective probability of survival

Source: Foltyn and Olsson (2021).

The problem is that this kind of misperception about life expectancy influences the decision to save for later quite significantly. If you are in your fifties and think you are going to die sooner than you can expect, you are not going to save as much as you need for retirement. And if you are 85 and think you are going to live to 100, you are going to spend less than you realistically could. The result is that people tend to save too little during their working life and too much during retirement.

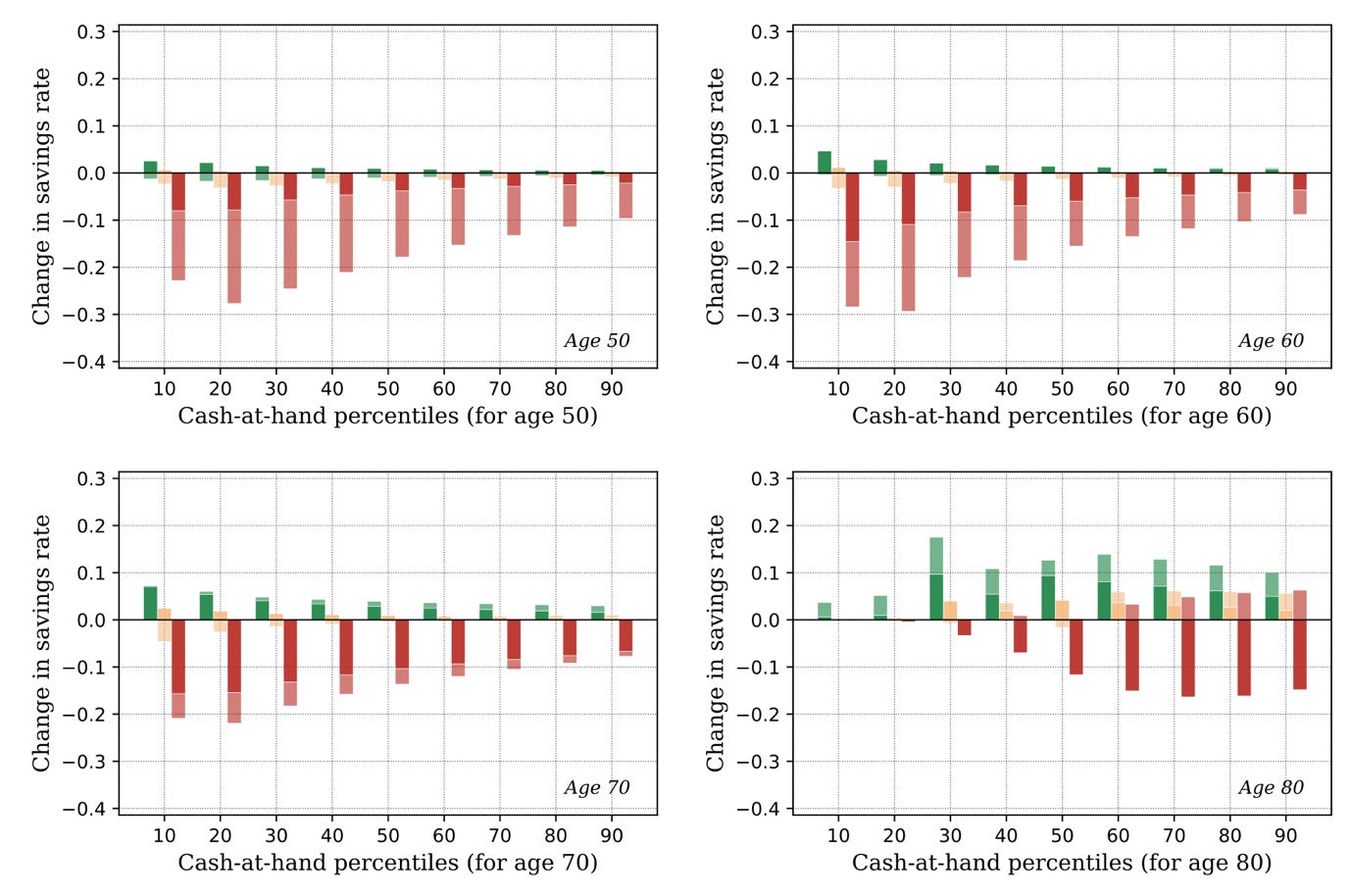

But what drives this misperception of life expectancy. In short, it is your health, or rather your perception of your health. The chart below shows the deviation in savings rate from the optimal savings rate of people in good health (green bars), moderate health (yellow), and poor health (red). A positive bar means that the savings rate of these people is higher than it needs to be given their life expectancy and living standards, a negative bar means that their savings rate is lower than it needs to be. The horizontal axis shows the amount of cash people had in their savings relative to all other Americans.

People in poor health save too little

Source: Foltyn and Olsson (2021).

At all ages, the people in poor health save too little and sometimes far too little. At ages 50 and 60, most people who perceive themselves to be in poor health save 10% to 20% less than they need to, while people in good health tend to save too much, though typically only a little too much. This difference in savings behaviour translates into vastly different wealth outcomes as can be seen below. People with poor health accumulate less wealth and run out of money sooner than people in good health.

Wealth over the lifecycle depending on health status

Source: Foltyn and Olsson (2021).

How can you avoid falling into that trap yourself or help your clients fall into that trap? In my view, the study shows that there are more benefits to regular health checks than one might expect. A regular health check helps a person get an accurate assessment of their health and thus reduces the bias in subjective life expectancy. Second, it helps detect severe illnesses like cancer earlier and thus reduces the probability to face a situation where such illnesses can end life prematurely. And third, it makes people save more for the future and improve their financial quality of life simply because people who get health checks more often feel healthier and are more inclined to make wise money decisions. ‘Healthy, wealthy, and wise’ may be true, though as a night owl, I doubt that ‘early to bed and early to rise’ has anything to do with it.