How a wage-price spiral looks like

Inflation in the US (and in my view also in the UK and the Eurozone) has peaked. This is at least in some part due to nominal wages not keeping up with inflation and thus not fuelling a wage-price spiral as we have seen in the 1970s. But the emergence of a wage-price spiral where higher inflation begets higher wages and higher wages, in turn, beget higher inflation is not off the card, yet. It is one of the possible risk scenarios for 2023 that we must understand.

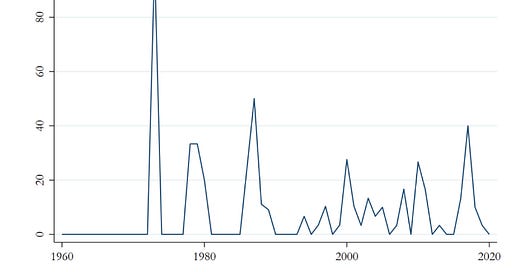

Thankfully, Jorge Alvarez and his colleagues have done a very timely and informative study on past wage-price spirals, how they evolved and what impact they had on real wages, unemployment and the like. To do that, they needed to define what constitutes a wage-price spiral and since there is no universally accepted definition, they had to come up with what I think I will adopt in the future as my definition as well. A period of at least three quarters in a row of rising consumer price inflation and rising nominal wage inflation. Applying this definition to 31 developed countries since 1960 gives you the chart below that shows what percentage of these 31 countries experienced a wage-price spiral. The 1973 episode stands out as the prime example of a global wage-price spiral. But in 1979 and again in 1985, we saw at least one-third of the developed world experience another such wage-price spiral. Since then, these events have become increasingly rare and localised.

Share of developed countries experiencing a wage-price spiral

Source: Alvarez et al. (2022)

But how do wage-price spirals evolve? The chart below shows the average path of inflation and unemployment (top row) and nominal and real wages (bottom row) once a wage-price spiral starts (time = 0 indicates three quarters of rising inflation and nominal wages in a row). Most investors will be familiar with the red lines in the chart denoting the episode triggered by the OPEC oil crisis in October 1973 that marked the start of the 1970s stagflation. Back then inflation got out of control and continued to rise for another six causing a large spike in unemployment. This is the risk that may materialise again this year. But note how unusual the 1973 episode was. The ‘typical’ evolution of a wage-price spiral is to see inflation top out slowly in the year after the spiral started and unemployment rates falling(!) not rising. Also, and this is I think something really important to remember, real wages first declined when the wage-price spiral took hold but then – about a year later – started to rise again, but only so much as to catch up with new price levels. In the three years after a wage-price spiral took hold, real wages did not show positive growth, which means the spiral eventually fizzles out and the economy normalises but at a higher price level.

Average impact of wage-price spirals on the economy

Source: Alvarez et al. (2022). Note: Time = 0 indicates three quarters of rising inflation and nominal wages in a row.

1973 then is a risk scenario that we should monitor, but not the main case of how wage-price spirals typically evolve. Furthermore, going into the current episode of rising inflation we had one important difference to 1973. Real wages were falling before the pandemic and the supply chain disruptions hit, not rising as in 1973. The authors of the study thankfully also show the typical evolution of such a spiral in the case when real wage growth was negative before the spiral took hold. The closest example of that is the late 1970s in the US when rising house prices and higher energy prices combined led to a wage-price spiral. In that case, real wages did indeed become positive but once again only to a degree as to catch up with inflation and to make up for real wage decline before and after the wage-price spiral took hold. In fact, real wage growth was only positive because nominal wage growth remained at roughly the same level for three years and that nominal wage growth was anchored by the peak of the wage-price spiral. As inflation came down nominal wage growth started to outpace inflation creating real wage growth to compensate for past negative real wage growth.

Average impact of wage-price spirals on the economy when real wage growth is negative

Source: Alvarez et al. (2022). Note: Time = 0 indicates three quarters of rising inflation and nominal wages in a row.

Where does that leave us in 2023? I think we will see rising unemployment as the developed world goes through recession. But the increase in unemployment rates may be smaller than what I and many others expect. This bears with it the risk that the Fed and other central banks use this stubbornly low unemployment rate as an excuse to continue hiking interest rates. That, in my view, would be a major mistake and would condemn us to a longer and deeper recession than most investors currently expect (or that is priced into markets). Don’t get fooled by low unemployment.

Second, I think we will see several years of continued high nominal wage growth that will eventually also translate into positive real wage growth. But this is not a reason to call for 1970s-style stagflation (though many doomsayers will). This is a normal process. The way to trigger a proper wage-price spiral is to cut interest rates and boost demand, thus creating a new wave of inflation with a premature dose of loose monetary policy like the Fed did in 1974. Don’t cut interest rates too soon.

So, the Fed and other central banks seem doomed if they hike interest rates too much and doomed if they cut too soon. What can they do? Personally, I think sometimes doing nothing can be the best policy, and I think that is what the Fed should do in 2023.