How do companies deal with inflation and supply chain disruptions?

Supply chain disruptions due to Covid have been the dominant theme in corporate earnings call for the last two years. Now, rampant energy prices, rising wage inflation and other cost pressures are added to the mix and corporate executives are wondering, how to deal with these issues in the medium- to long-term.

In May 2020, I wrote a three-part series on the World after covid as I saw it back then (available to subscribers of Liberum research). In part 2 of that series, I hypothesised that companies might react to supply chain disruptions with two measures:

They will diversify their supply chains globally, in order to reduce the dependence on a small number of countries in East or South Asia. In particular, it seemed likely to me that companies will try to find outsourcing partners in countries that are closer to home like Turkey and southeast Europe for the UK and European companies and Mexico and the Caribbean for North American companies.

They will onshore production processes only if they can automatise and digitalise these processes in order to keep labour costs under control. This should accelerate the fourth industrial revolution and the further rise of robotics, etc.

A new study of earnings calls by 5,723 US companies shows that both of these trends seem to materialise. Suppliers hit harder by the supply chain disruptions of the last two years trying to establish new supplier relationships, in particular with suppliers on their own continent and with industry-leading suppliers. What they also seem to do is try to remove supply chain dependencies. That can be done by increasing automatization as I have suggested, but also – and I did not expect that – by increased M&A activity to become a vertically integrated business. By acquiring suppliers, a company guarantees access to its core supplies.

This makes particular sense in a high inflation world. One key corporate trend of the inflationary period in the 1970s was for companies to become vertically integrated. By doing that, you could control the prices of input factors and avoid markups by the producers of raw materials and intermediate products. The problem with the vertical integration strategy is that it risks losing focus and creating internal overhead that is hard to get rid of. When the inflation of the 1970s subsided in the 1980s, corporate raiders were busy slicing and dicing bloated conglomerates and integrated companies with disjunct operations. Lean and mean became the mantra of the last four decades of falling inflation. Whether we are going back to the vertical integration trend of the 1970s will be decided by inflation more than supply chain disruptions, in my view.

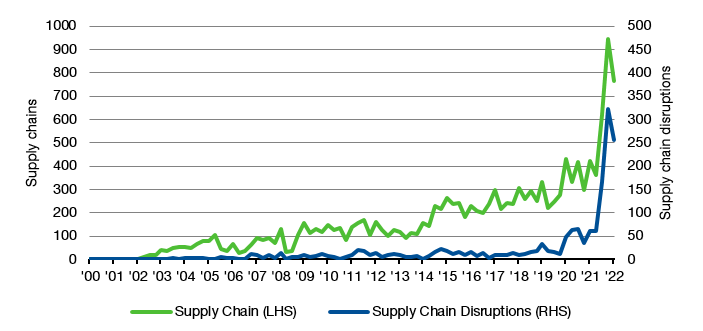

Mentions of “supply chain” and “supply chain disruption” in earnings calls of UK companies

Source: Bloomberg