How far can inequality rise?

One of the defining features of the post-GFC political debate is the increase in inequality observed in both developed and developing countries. Oftentimes, the discussion focuses on the Top 1%, though, which Top 1% one means is not always clear. The Top 1% income earners are not the same people as the Top 1% wealth owners. Of course, both income inequality and wealth inequality lead to social tensions but in my view wealth inequality is more corrosive because it can become self-perpetuating.

I have no problem with people who are successful entrepreneurs and generate massive wealth through hard labour and their ability to build a business. I also have no problem with people who happened to inherit a lot of money but use that money to grow a successful business. I have far less sympathy for trust fund kids who benefit from that wealth and earn high incomes because they happen to be the children of these successful entrepreneurs and don’t do anything themselves to further that wealth or use it to the benefit of society. Successful families ensure that wealth is stewarded across many generations and children and grandchildren don’t become spoilt trust fund kids. Instead, every generation has to contribute to society and the family business. But not all families are that enlightened. And when the public witnesses privileged behaviour by people who did nothing to earn that privilege then I am not surprised if it causes outrage and a public backlash. As John D. Rockefeller has said (and engraved in Rockefeller Center in New York City):

“I believe that every right implies a responsibility, every opportunity, an obligation, every possession, a duty.”

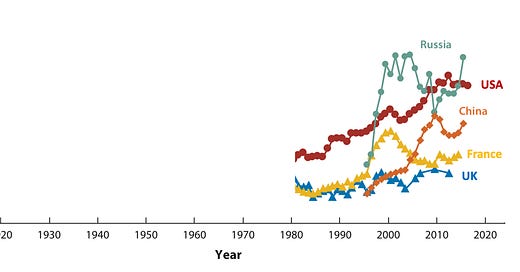

If we look at the state of wealth inequality today, we see that since 1980, it has dramatically increased. In the US, the Top 1% wealth owners used to own around 25% of total wealth around 1980 but this share has since increased to about 40%. In China, wealth inequality has doubled from 15% to 30% and in Russia it has almost doubled from 22% to 43%. Only in the UK did the share of wealth of the Top 1% remain stable at about 15% to 20%.

Share of total assets owned by Top 1% wealth owners

Source: Zucman (2019).

The question, of course, is how much can inequality rise before we face civil uprising or severe political backlash in the form of extreme redistribution of the kind the Labour Party wants to implement in the UK? And here my answer is that it can get a lot worse. The chart above is an abridged version of a chart from a new paper of Gabriel Zucman in the Annual Review of Economics and is reproduced in its full glory (or horror, depending on your point of view) below.

Share of total assets owned by Top 1% wealth owners

Source: Zucman (2019).

In the early part of the 20th century, wealth inequality in the US, the UK, and France was far greater than today. In particular, the colonial powers were able to provide their landed gentry with untold fortunes and suffered from tremendous inequality. Of course, in Czarist Russia, this inequality led to civil uprising and the rise of Communism, but in Western Europe and the US, nothing of that sort happened. The decline in inequality in the US was driven by the Great Depression, the break-up of trusts under President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the introduction of an improved social safety net as part of the New Deal. In France and the UK, the decline in inequality was driven by two devastating world wars and the loss of Empire.

In his book The Great Leveller, Stanford Professor Walter Scheidel meticulously tracks income inequality from the Roman Empire to today and tries to identify the triggers for a decline in income inequality. Unfortunately, he can only come up with four types of events that reliably reduced inequality:

War: This has been a major driving force behind the reduction of inequality in Europe in the middle of the 20th century.

Revolution: See Russia in 1917 and France in 1789.

Systems collapse, for example due to natural catastrophes like earthquakes or volcanic eruptions.

Plagues, like the Black Death in the Middle Ages.

Peaceful social reform or increasing educational attainment have almost never been able to provide a lasting decline in inequality.

Thus, going back to my ten rules of forecasting, I am inclined to predict that inequality will continue to rise for some time in the future. In the early parts of the 20th century when inequality was driven by owning both capital and land (much of the wealth of the nobility was the land they owned both at home and overseas). Today, wealth creation happens mostly by investing capital into businesses (either directly or through the stock market) and in fixed income investments. Unfortunately, though, stocks are disproportionately held by the wealthy, while poorer households disproportionately invest in fixed income investments like money market funds and bonds.

Since the 1980s, the real rate of return on capital has been significantly higher than the real risk-free rate of return – a key driver of the recent increase in wealth inequality. And while the real return on capital has declined somewhat since the Global Financial Crisis, the gap remains exceptionally large. As long as the gap between the real return of risky and risk-free investments remains that large, we have to expect inequality to rise. Until we hit a breaking point, that is, and I am afraid, history tells us that at that breaking point, things will become very ugly indeed. Luckily, history also indicates tat this breaking point may well be decades away.

Real return on capital in the US and UK and real risk-free rate in the US

Source: AMACO database.