How the Fed rotation changes monetary policy

It’s another Fed Day, and the seven Federal Reserve Governors and the five voting regional FRB Presidents have to make up their minds on whether to cut interest rates or not. And then there are the other seven regional FRB Presidents who sit in the meetings but have no votes. And, as you might guess, who votes and who does not matters.

The Federal Reserve is made up of 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks. Together with the Federal Reserve Governors, they form the Fed Open Market Committee (FOMC). To keep things manageable, who votes for rate cuts (or hikes) is restricted to the seven Fed Governors, the President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and an annual rotation of the other regional FRB Presidents. This makes an awful lot of sense because it (i) ensures every region of the country has a voice, and (ii) keeps the size of the meeting and deliberations manageable and prevents it from descending into a debate club.

However, Vyacheslav Fos and Nancy Xu from Boston College noticed something important. Inflation and unemployment are not constant across the United States, and regional FRB Presidents are naturally more influenced by the economic conditions in their area of the country than others. That means that if by accident, the voting members of the FOMC are all from a low inflation area of the country while the non-voting members are from higher-inflation areas, the Fed decision is likely to be tilted in favour of a rate cut, even though that rate cut may not be optimal from a national perspective.

When I came across their paper, my initial reaction was: So what? The regional members rotate, so while this may temporarily shift Fed Funds Rates higher or lower, in the long run, the bias should be relatively small. Alas, that is decidedly not the case because regional members are not always presented with the same choice.

In general, the choice for voting members is between a rate cut and a hold, or a rate hike and a hold, not between a cut, a hold, and a hike. Hence, the resulting Fed Funds Rate depends on which regional voting member is rotated in or out during a rate hike cycle and a cut cycle. If in a rate-hiking cycle, regional members are rotated in that come from a low-inflation region, the Fed Funds Rate will rise less than optimally. And that subsequently limits the possibilities of the voting members during the rate cut cycle.

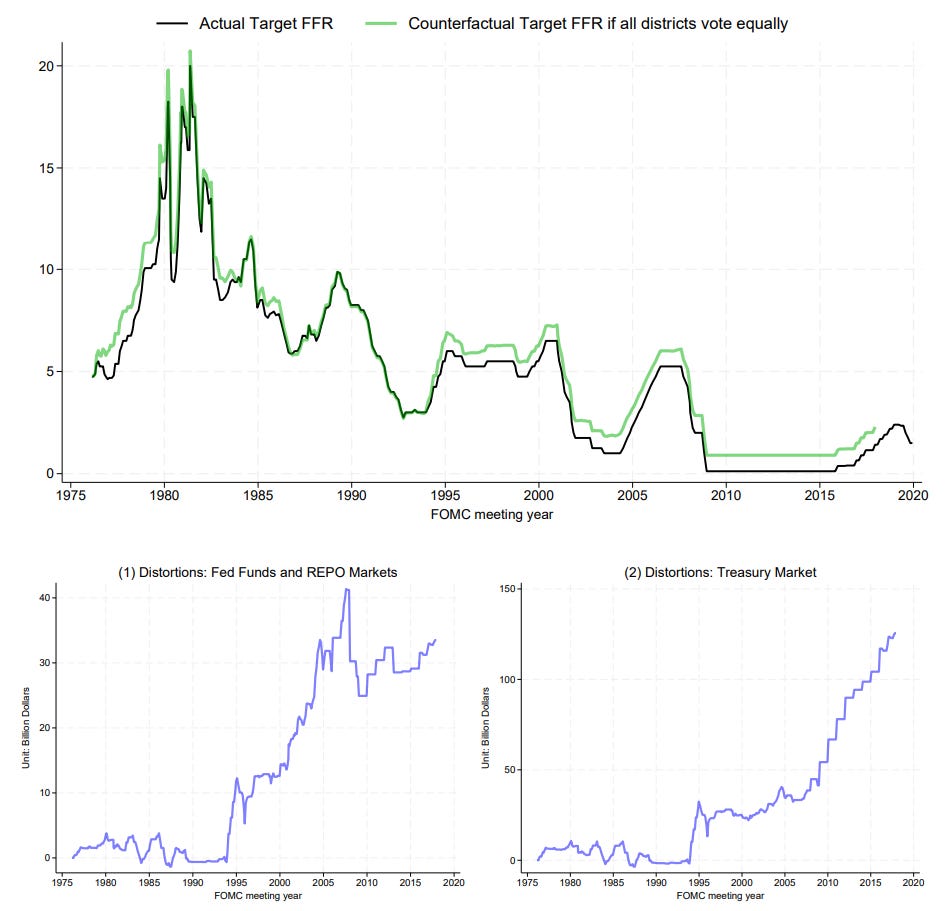

To give you an idea, the following are the three key charts from the paper. The top chart calculates the Fed Funds Rate if all regional members were allowed to vote at all meetings and compares it with the actual Fed Funds Rate.

As you can see, the rotation system led, on average, to a lower Fed Funds Rate than if all regional members could vote all the time. This happened by accident as the rotation overlapped with different stages of the business cycle, but the result is that if all regional members were always allowed to vote, the Fed Funds Rate would be an estimated 100 basis points higher today. We would still be talking about Fed Funds Rates of 5% today, rather than 4%.

And banks and the US Treasury better thank the Fed that this is not the case. The charts on the bottom show that if all regional members determined the Fed Funds Rate, the Repo market would be $30bn larger and the US national debt would be some $130bn larger as well to cover the larger interest cost.

Fed Funds Rate if all regional members could vote all the time

Source: Fos and Xu (2025)

This is fascinating! Thanks.