In the UK, valuations of companies (in particular small- and mid-cap companies) have been so low for years that we have seen a boom in takeovers from international companies and private equity firms. Between 2022 and 2024, the average premium paid for a takeover in the UK was 38% over the last share price. If you get such a sweet deal, why shouldn’t you say yes if you are approached by a potential buyer?

Because a database compiled by Morgan Ricks and Da Lin tells us that the chances of getting the same or a better deal are about 94%. Their database covers more than 5,000 mergers and acquisitions targeted at US listed companies between 1996 and 2020. The results maybe different in the UK and other countries, but since this is the only database of M&A success rates I know of, we have to take what we get.

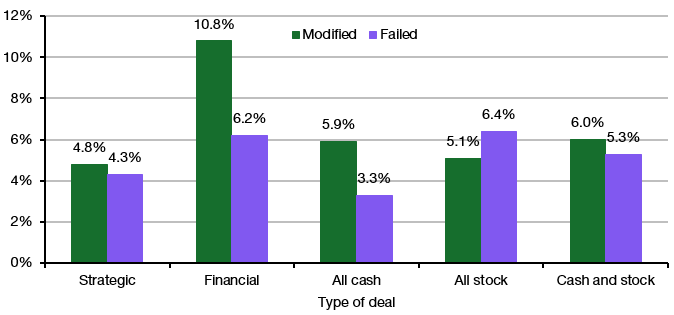

Interestingly, about 90% of all deals are accepted on the original terms, no matter whether it is paid for by cash or stock. Purely financial deals have a somewhat higher modification rate than strategic deals, but not a lot higher failure rate. Indeed, the share of deals that fail altogether is astonishingly low, independent of deal type, and typically hovers between 4 % and 6%. Only one in every 20 deals fails.

Modification and failure rate of M&A deals

Source: Ricks and Lin (2024)

If we look at how deals are modified, we can see that they typically get modified to the advantage of the target, not the acquirer.

Who gets a better deal if the deal is modified?

Source: Ricks and Lin (2024)

If we look at the relative frequency, conditional of the deal being modified, we can see that targets get a better deal in about four out of five cases.

Who gets a better deal if the deal is modified?

Source: Ricks and Lin (2024)

In short, if you are a company that is approached with a takeover bid, rule number one is to fight for a better deal. The chance of the bidder walking away is very low indeed and if the deal is modified, there is an 80% chance you get more money for the business. Put it all together and you have a 90% chance of getting the same deal plus a 4% chance of getting a better deal for a total chance of 94% to get at least the initial deal if you play coy and don’t just roll over at a seemingly attractive offer. Typically, even if the initial offer looks great, there is some reserve that the acquirer is willing to pay and targeted businesses should fight for it.

Whilst the gist of the research is accurate, and good negotiations can improve an initial offer for a buyer, there are still many pitfalls between initial offer and the price ultimately paid. For smaller entities, two things tend to happen;

1. Shortly before the altar, the buyer significantly reduces their offer in a surprise move. This is made on a 'take it or leave it' basis, at which point the exclusive due diligence phase has left other prospective acquirers behind. It takes some nerve to walk away from the wedding. It would be very interesting to see if the researchers found out what proportion of deals were 'knocked' at the last minute.

2. Most unlisted transactions will contain performance clauses, so the buyer can be certain that promises and warranties will be made good. Inevitably sales or other financial forecasts were over-optimistic, a client cancels a project, or a key employee misses their autonomy and moves (is lured) away before their earn out period. This will reduce the overall transaction payment.