In praise of the (good) middle manager

Half a year ago, I wrote about the drive for flat hierarchies and how it destroys productivity. It created a lot of discussions, and I got some interesting responses from readers, so let’s see how you react to today’s post.

If I would ask you how important middle managers are in a company, most of us would intuitively say they are not very important. After all, their job is to push paper, manage people and run meetings that often feel unnecessary. Scott Adams has built a career out of the imaginary software engineer Dilbert’s struggle with his incompetent managers. And I agree, that incompetent middle managers are horrible and destroy motivation and productivity. But has anyone thought that that also means that competent middle managers could potentially boost productivity a lot?

A decade ago, Ethan Mollick from Wharton examined the influence game developers and middle managers have on the productivity and success of video games. Video game companies are knowledge companies just like most tech companies and indeed most companies across industries today. So, naturally, a firm tries to hire the best developers they can find in the hope that these whizz-kids will create innovative new games and implement their ideas in the most efficient way possible. Often, little thought is given to the middle managers and their role in the process.

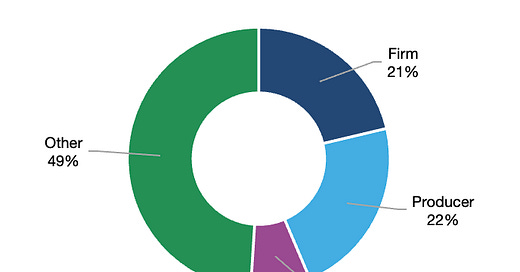

But as the results of Mollick’s research show, middle managers have about three times higher influence on the outcome than individual game designers or software engineers. The variation in video game success explained by middle managers is about 22% compared to about 8% for game developers. In other words, replacing a poor middle manager with a good one can increase game revenues by a quarter. That should be motivation enough for executives to look at the quality of their middle managers. And it should be incentive enough for equity analysts to ask more probing questions about the management culture of the companies they cover. And by management culture, I mean mostly the on-the-ground management culture of middle managers, not just the executives.

Variation in video game success explained by different factors

Source: Mollick (2011)

A new study has looked into the automotive industry and found a smaller influence of middle management on the productivity of car companies. Yet, the variation of outcome explained by middle management was still substantial. Given that the automotive industry is less of a knowledge industry and more automatised and standardised than software development that is not too surprising. If you deal with standardised processes and value chains there is less room for managers to screw things up, but also less room to improve productivity.

Yet, that new study gives us another hint of what to do and what not to do in a company. The study found that middle managers who are in their jobs for longer tend to have more productive teams. And when models change, the drop in productivity is smaller for managers that have been working for a longer time in their plants and their current role than for managers who are new in that plant or that role.

This of course means that one shouldn’t move middle managers around too much. The trend in large corporations to move middle managers from one job to another every two or three years is one of the practices that destroy productivity because with every new middle manager this guy (or girl) has to learn the processes from scratch again and is tempted to fiddle with the team and the processes, thus creating a larger drop in productivity.

In the end, what seems to be a key determinant to increasing productivity is to hire good middle managers, get rid of the poor ones, and don’t rotate the good middle managers in and out of jobs or give them new responsibilities. Let them do their job and let them do it for a long time.