Last Monday, I wrote about the research on collective intelligence which shows that team performance is not driven by the intelligence of the team members but by their ability to work together in a cooperative and constructive way – the collective intelligence of the team. As I discussed there, three factors can increase collective intelligence: (i) the emotional intelligence of the team members, (ii) the speaking behaviour of the team, and (iii) the share of women in the team. But more recent research has supplied some fascinating nuance on that picture.

Since the original research more than a decade ago, the world has moved on and today, the focus in understanding collective intelligence is very much on ‘collective attention’. Collective attention, aka ‘shared attention’ or ‘group attention’, describes the degree to which team members focus on team tasks rather than their personal goals and how ‘involved’ team members are with the team.

For example, a team with high levels of collective attention is one where team members put a high priority on the shared goals and coordinate their actions while low levels of collective attention are characterised by team members emphasising their own goals and tasks over the team goals.

Collective attention is increased if team members work on a task simultaneously or share more of the information among the team. Or it is increased if all team members have similar speaking times in meetings and are encouraged to contribute equitably to the team task. This is why people with high emotional intelligence are needed to make a team successful. They are able to pick up on nonverbal cues from other team members and use them to bring out dissent or make people feel comfortable in a team, encourage introverts, rein in the overpowering extroverts, etc.

The problem is that in the business world, teams don’t exist in a vacuum. Teams are built within an existing hierarchy and where there is a hierarchy, there are people who are more senior than others, and that can lead to more senior people dominating the conversation, thus reducing collective attention and collective intelligence.

In one of her latest research papers, Anita Woolley and her collaborators addressed this problem and tried to figure out if a hierarchical or a non-hierarchical team structure leads to higher collective attention.

Intuitively, I would have thought that a flat hierarchy may be beneficial to increasing collective attention, but it seems that quite the opposite is true in most cases.

The chart below shows how synchronised team members were in team tasks and what impact that had on collective intelligence and the performance of the team overall. Note that these results are based on lab experiments with teams of four people. For almost all cases, higher synchrony between team members leads to higher collective attention and finally higher collective intelligence. The benefits increase, the more women are on the team. Essentially, this chart shows that in a mixed-gender team, increasing synchrony leads to better outcomes for the team.

Impact of synchrony and gender composition on collective intelligence

Source: Woolley et al. (2023)

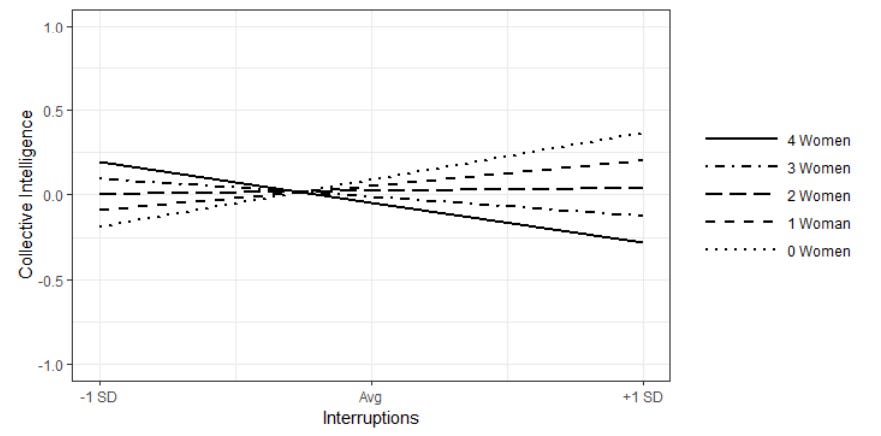

You can turn the measure around and look at how many times people in the team were interrupted by other team members. Here you see the opposite effect. The more interruptions there were in the team discussion, the lower the collective intelligence.

Impact of interruptions and gender composition on collective intelligence

Source: Woolley et al. (2023)

Yet, notice how this trend holds for all but one case. When a team has zero women in it, the link between collective attention and collective intelligence flips. More interruptions lead to higher collective intelligence in all-male teams.

What the research shows is that men thrive in an environment where they try to overpower their team members, while mixed-gender teams and all-female teams thrive in an environment that is more respectful to the individual and allows every team member to freely and uninterruptedly express their views. And let’s face it, as long as you live outside of Afghanistan, chances are you will work in mixed-gender teams, not the all-male, testosterone-saturated clubs of the Victorian age. I know some people may wish we could ban women from the workplace, but even the military now allows women to join, so get used to it.

Where was I? Ah, yes, hierarchies and collective intelligence. What seems like a tangent explains why hierarchical teams are more effective than teams with no hierarchy or unstable and changing hierarchies.

If you work in a flat hierarchy or a team without any clear and stable hierarchy, what happens is that all the team members constantly have to assert their status in the team. The result is that team members try to outdo each other with their contributions, constantly interrupting other team members in discussions and focusing on their contribution to the team task to ensure they look good to other team members rather than prioritising the team task.

If people were asked to work in a team with a given hierarchy and clearly defined team leadership, the individual team members had no incentive to outdo their team members. There is no point in jockeying for position if the hierarchy in the team isn’t going to change. The result was that teams with clear hierarchies had better conversations, worked together more productively and cooperatively, and showed altogether higher collective intelligence which led to better team performance.

Two years ago, I wrote a post on why I think flat hierarchies are bad for productivity in the workplace and that there is a reason why the military insists on hierarchies. I got criticised by some readers saying that while the hierarchy may be needed in the military, more creative tasks are better solved in a flat hierarchy. Well, here is empirical evidence that flat hierarchies are also bad for more creative tasks that require high degrees of collective intelligence.

I find in creative industries (or just creative discussions) you need hierarchy, someone to stir the conversation but you can't have a military type of hierarchy where people execute orders. On the other hand, anyone can suggest ideas. So it's not about hierachy Vs flat it's about hierachy (structure) in the process and flat (all can contribute equally) when it comes to ideas

Fascinating stuff.

Random thoughts: "Collective attention": this brought to mind how much the Japanese value ostentative attention. In fact, attention is considered one of the prime virtues, and the basis of politeness.

And yet... in so many Japanese workplaces, you won't hear many female voices upping the discourse level, because there're still not many around.