Many people expect this century to be the Chinese century with China becoming the dominant economy of the world. This is likely to be the case in the next decade or two, but if we look further into the future, the answer could be very different.

Seth Benzell and his colleagues ran a long-term forecasting model for the global economy. Intuitively, these forecasts should be easier than forecasts for the next one to three years, because they can ignore the messy world of business cycles. Instead, they rely essentially on three key factors: demographics, investments, and productivity.

Demographics are the easiest variable to forecast since people live quite a long time and fertility rates are generally relatively stable. So, the researchers took the projections from the UN Population Division and plugged these into their model.

Investment activity is harder to forecast because it requires us to project savings rates. Remember from university classes that I=S. We can only invest what we don’t consume today, so investments are fuelled by savings. But estimating savings means we need to make assumptions about wages, tax rates, etc. That sounds daunting but luckily it can be done with reasonable precision.

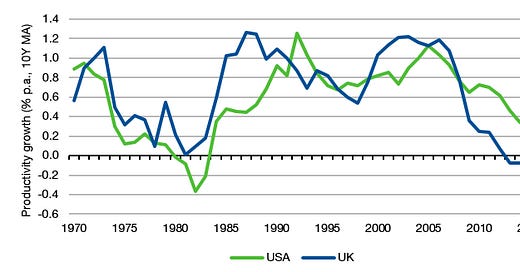

This brings us to the third component, productivity. This is where our ability to forecast almost completely breaks down. We really don’t know what drives productivity (or rather total factor productivity in a Solow growth model, to be precise). 20 or 30 years ago, people expected the internet and computer technology to increase productivity growth significantly in developed countries. Yet, all that happened was a short-lived increase in productivity growth in the early 2000s from c0.8% per year to 1.2% per year. And since the financial crisis, productivity growth has essentially slowed down to zero. This is despite all the technical revolutions that have been touted as life-changing, from personal computers to the internet, mobile phones to robotics and AI. If these technologies are such a boost to productivity, why can nobody see their impact on productivity data?

10-year average productivity growth in the US and UK

Source: Penn World Tables

The fact is, we live in a world with low productivity growth, and we don’t know if, when and how that will change. But this is also what makes long-term forecasts nigh impossible.

Benzell and his colleagues try to get a handle on this productivity problem by running three different forecasts:

A univariate model, where the productivity in each country or region is modelled independently without influence from other countries.

A multivariate model in which productivity in one country influences productivity in other countries through technology transfer and where in the long run, productivity growth across the world approaches the average of the most developed countries.

A model that uses productivity growth trends from 1997 to 2017 as the ones that will persist for the rest of this century.

The chart below shows the resulting share of global GDP for several major regions in the year 2100.

In the univariate model, China will be the largest economy in the world in 2100, producing some 27% of global output. India will be the second largest economy accounting for 16.2% of global output and the US will be third with 12.3% of global output. So, it’s the century of China then.

But if you look at the output of the multivariate model, China in 2100 will be much smaller than both the US and India. The US economy in this model would account for 18.1% of global output, India for 8.0% and China for 7.8%. Sub-Saharan Africa, meanwhile, would grow to a massive 17.5% of global output as Africa finally catches up with Western productivity rates. So, it would be the century of Africa then.

Not so fast, because if productivity trends of the last 20 years can be sustained, India will become the world’s largest economy at 33.8% of global GDP, while China would account for 22.2% and the US for 10.0%.

In short, it is a mess and people can make the case for any future they like. We simply don’t know which countries will become the dominant economies in a future that is more than 20 to 30 years away.

Projected share of global GDP in the year 2100

Source: Benzell et al. (2022)

Great post! Knowing who will be number one in 80 years is clearly a hard thing to do, but nevertheless I think we can agree that US, India, China and Africa together will represent a very large part of economic output in any case and in this regard, being invested in each looks like a good thing to do if we keep the time horizon for the investment the same as the analysis.