Maybe you have asked yourself in the past why the momentum factor is defined as 12-1 month returns where the return of the last 12 months is reduced by the return in the previous month. Ok, if you have asked yourself that you are officially a finance nerd and need to get a life, but really, why do we not simply use the return of the last 12 months as a measure of price momentum?

The answer, my friend, is not blowing in the wind, but rather reversing in the wind. The short-term reversal effect, which was first described in 1985, states that stocks that had particularly strong price momentum in the previous month experience particularly weak returns in the current month and vice versa.

There are different theories on why stocks should experience short-term reversal, but the most intuitive is one where investors overreact to recent news. Positive news leads to more people buying the shares, pushing the price up. But after a couple of days or weeks this buying pressure declines, and the share price drops as investors correct their overly optimistic beliefs.

There is just one problem with the short-term reversal effect. It has been missing in action for the last 20 to 30 years.

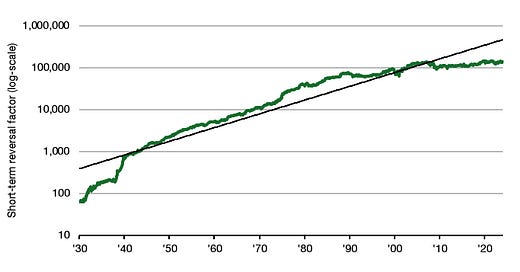

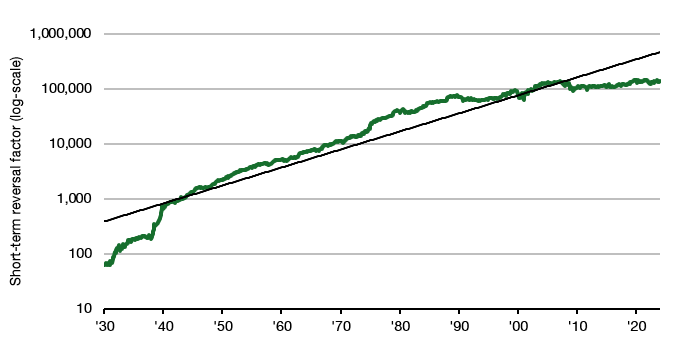

I have taken the data from Ken French’s database for the short-term reversal effect in US stocks since 1926. The chart below shows the performance of that factor together with the best fit of an exponential growth of constant returns (nerd alert: the y-axis is a logarithmic axis which is why an exponential curve looks like a straight line). As you can see, since the 1990s there has been hardly any return on the strategy.

The short-term reversal effect has not delivered returns since the 1990s

Source: Liberum, Ken French Database

The great team around David Blitz at Robeco has shown that that this is not just a US phenomenon but also happened in Europe. Only in the Pacific region is the short-term reversal effect still alive.

What this means is simple: For all practical purposes just taking the return of the last 12 months as a measure of momentum is likely to give you very similar results as the more academically correct 12-1 month momentum. Did I mention that these posts are about what works in real life rather than what works in some theory? This is one of these examples.

To resurrect the short-term reversal effect from the dead, the team at Robeco makes different suggestions and tweaks the data in different ways, but I wanted to focus on a different paper that I find intriguing in its simplicity. Though admittedly, one can argue about the quality of the arguments made in the paper, I find the intuition behind it rather intriguing.

The paper starts with the, in my view correct, assumption that stocks are not treated equally by investors, but instead, some stocks are more ‘salient’ to investors than others. And they claim that stocks that have particularly strong deviations from recent price trends are more salient than others.

For example, consider two stocks that both have rallied by 11% from 12 months ago to one month ago. If we apply the academic definition of price momentum, both stocks have identical momentum. Then, in the previous month, one stock rises another 1% while the other stock drops by 1%. The authors argue that the stock that rose another 1% last month after rising pretty much 1% per month for the previous 11 months will be less salient to investors than the stock that first rose 11% and then suddenly dropped 1%. The contrast between last month’s performance and previous performance is what makes a stock salient and the bigger the contrast, the more salient the stock will be in investors’ minds.

But if a stock is more salient investors are more likely to react to more recent performance. In our example, the stock that dropped last month will attract more attention from investors and more of them will sell the stock to lock in previous gains and prevent further losses. The result is that selling pressure for that stock persists in the very short term, but the bounce back afterward should be stronger. If the most recent drop was just a fluke and the company continues to provide positive fundamental news, the stock that sold off in the short term should rally more in the coming month than the stock that just moved higher in an orderly and rather boring fashion. The bigger the zig, the more aggressive the zag.

Note that the prediction of this theory is not the same as the short-term reversal effect. The short-term reversal effect would anticipate both stocks to drop in the next month because of their strong past performance, but this salience-driven explanation implies that both stocks bounce next month, creating no short-term reversal effect at all.

The researchers test whether their effect is the same as the short-term reversal effect and they find that it isn’t. However, they do find that their effect leads to significant outperformance, much unlike the short-term reversal effect.

They test their theory in the US stock market between 1965 and 2019 and in 38 international stock markets from 1991 to 2019. In each market, they test the performance of the stocks with the strongest positive short-term salience effect (i.e. stocks with the strongest contrast between positive returns twelve months to one month ago and negative returns last month) vs. the stocks with the strongest negative short-term salience effect (i.e. stocks with the strongest contrast between negative returns twelve months to one month ago and positive returns last month).

The chart below shows that in most markets this long-short strategy has significant monthly outperformance (before costs). To me, this looks like something that needs to be explored more, in particular concerning transaction costs and if this outperformance persists in the real world as well where there are all kinds of costs involved.

Monthly outperformance of a long-short salience momentum strategy

Source: Guo et al. (2024)

This might fall into the category of old saws about the press: "If it bleeds it leads", or "man bites dog stories are a lot more interesting than dog bites man stories". I've always chuckled to myself how amongst finance professionals and investors, stocks "go up" or "go down", perhaps with a modifier "a lot" depending on the severity, but in the press, stocks only ever "plunge" or "soar". I've also noticed something that's crept into press coverage of stocks over the last few years that was never used in my early days in the business: "Stock XYZ was -5% in yesterday's trading, the most in 14 months." I have never been able to figure out why, having been unremarkable for decades, this is suddenly worthy of comment, especially because that historic volatility is never de-constructed to back out the impact of a sector or market pull-back. I think they only do it only because that statistic is now more accessable.

When I was a young analyst, I once had a buy rating on a stock which was bid for and the stock was +25% in one day. An older salesperson said to me "you can't take credit for that outperformance, because that's M&A!" I replied "so in your eyes, only if it've ground up +1% a month for two years would I have been a hero?" People are weird.

There may also be bias caused by computer program trading. We've all heard of "stop losses", but I've never heard of "stop gains". I always found this asymmetry interesting, as I'm convinced top-slicing winners and back-filling high-conviction laggards is a winning strategy, as opposed to just letting winning positions ride until they eventually have a down day which turns everyone into panic sellers. Perhaps "FOMO" is a stronger emotion than "patiently harvest your gains".

Excellent!

And having only skimmed the research, one wonders where the national differences in the importance of salience comes from. Is the Gamestop phenomenon dependent on Crameresque figures, preaching from the pulpit of the Church of What's Happening Now? Financial social media? Bank advisors?

In any case, it's no surprise that recent gains beget short-term future gains. We live in a shooting star economy, where every company (potentially) has its 15 minutes of fame.