Is this the reason why US profit margins remain so high?

One of the eternal frustrations of long-term investors with the US stock markets is that the profit margins of US companies seem to have a case of Alzheimer’s: they forget that profit margins are supposed to be mean-reverting. In theory, and in fact for many decades also in practice, profit margins were a main driver for the cyclicality of equity returns. In boom times, companies sell more stuff and can increase prices on their products. This increases their profit margins. Unfortunately, if an industry has persistently high profit margins, it attracts new entrants which increases competition and – eventually – lowers profit margins. Conversely, if an industry has persistently low profit margins, some businesses will exit the industry, either through bankruptcy or changing their business model. The result is less competition between the remaining companies and rising profit margins.

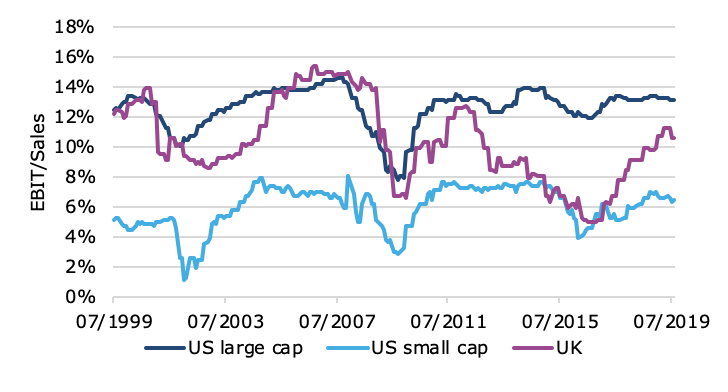

But as the chart below shows, US large cap stocks have seen virtually no cyclical variation in profit margins since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008. While both UK stocks and US small cap stocks have experienced significant swings in profit margins sine the GFC, US large caps have moved along steadily. Over the last ten years, the monthly variation in profit margins for UK stocks is almost twice as high as for US large cap stocks and for US small caps it is about one fifth higher than for US large caps.

Profit margins of US and UK stocks

Source: Bloomberg.

One possible explanation for this phenomenon has now been put forward by Gustavo Grullon, Yelena Larkin and Roni Michaely: Less competition and increased concentration of market power.

They looked at the market share of US businesses in 99 industry subgroups and calculated different measures of industry concentration. The Herfindahl Index is the most common measure of industry concentration. It is calculated in such a way that higher levels of the index indicate higher degrees of industry concentration and lower competition and in a monopoly, it reaches one. The chart below (taken from their research) shows that over the (almost) two decades from 1997 to 2014, three quarter of all US industries saw an increase in industry concentration. In some industries the increase in concentration was so big that the average increase in the Herfindahl Index reached 90%.

Herfindahl Index of industry concentration. Change 1997 to 2014 in the US

Source: Grullon et al. (2019).

Their study found that this increase in industry concentration led to two effects. Companies were able to charge systematically higher markups on their products which led to higher profit margins. At the same time, asset utilization and operational inefficiency declined.

This is the typical pattern observed in industries that move from being competitive to becoming a monopoly or oligopoly and it is both good and bad news. On the positive side, investors in stocks that enjoy a more dominant market position usually enjoy higher returns because these companies have systematically higher profitability which translates into higher stock returns. This is something that the authors of the study also observed in their sample. On the negative side, a more dominant market position leads to lower innovation and less productivity growth, which in the long run is not only bad for consumers, but also for shareholders if necessary investments are delayed or avoided leading to higher costs that eventually may lead to systematically lower investment returns.

One can speculate what caused this increase in market concentration in the US and there are two major candidates. First, the rise of technology means that larger forms could potentially reap higher rewards from digitizing their production and their services. However, in this case one would also expect to see higher operational efficiency of these companies, something that is missing in the data. Second, the lax enforcement of antitrust laws amongst both Democratic and Republican administrations may have led to a slow increase in industry concentration over time that triggered the observed effects. The recent antitrust investigations in Facebook, Amazon, Apple and Google seem to indicate that at least politicians are waking up to that possibility. If this is really the case, though, is unclear so far.