It’s a little bit more complicated than that

When it comes to making a point, there is a fine line between being nuanced and accurate and oversimplifying things to emphasise a conclusion. While I try to be subtle in these missives, I sometimes cross the line and become overly simplistic. Every time that happens, I get several emails from readers complaining about my being overly simplistic. So, thank you all for providing me with checks and balances. I mean it. To give you an example, I would like to focus on a country I have seen discussed more often than usual in recent months, which is close to my heart: Hungary.

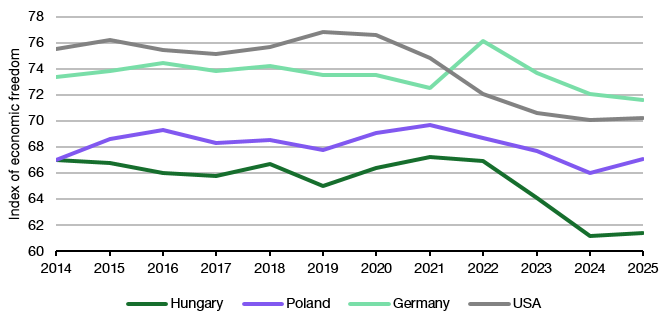

In the current US political climate, Hungary and Poland act as case studies for the effects that democratic backsliding can have. Commentators on the left of centre in the US point to Hungary as an example of how an illiberal democracy can ruin a country both economically and socially. They point to the decline in Hungary’s ratings in the Index of Economic Freedom, calculated by the right-wing think tank Heritage Foundation. There, Hungary ranks as the second-lowest country in the EU.

Meanwhile, commentators to the right of centre point to Poland and Hungary as examples of countries in Europe that have seen strong GDP growth and attribute this economic success to the leadership of the Law and Justice Party in Poland and Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz in Hungary.

Full disclosure, both my parents are from Hungary, and my father was a refugee after the civil uprising against the communists in 1956, so I have a somewhat emotional connection to Hungary. I don’t like either of the stories about Hungary (and Poland, for that matter).

So, let’s dive into the different arguments and check if Hungary and Poland are the authoritarian hellholes people on the left say they are or the economic paradise, people on the right say they are.

Let’s look at the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom, which shows a decline in Hungary in recent years. However, under Biden, other countries like Germany and the US have also seen a decrease in their scores, while more authoritarian Poland has seen stable ratings. If Hungary’s decline is due to the policies of Viktor Orbán, why do we not see a similar decline under the previous government in Poland? And why do we see a decrease in Germany under a consistently democratic and liberal government? It just doesn’t add up.

Index of Economic Freedom

Source: Heritage Foundation

Similarly, you are missing a big part of the story if you consider Hungary and Poland economic powerhouses. In the table below, I have examined the changes in key economic indicators over the last 10 years in Hungary and Poland and compared them to the EU overall. More importantly, I rank Hungary and Poland within the 27 EU member countries.

Hungary and Poland’s economic scorecard among EU countries

Source: Eurostat

Looking at the first two lines in the table, you see that Hungary and Poland are economic powerhouses if you measure GDP growth and GDP/capita growth. Poland ranks fourth in the EU, while Hungary is in the top 10. That is impressive.

But I am unsure if that results from local government policies. Hungary, in particular, benefited in the 2010s from significant investments in the country, particularly by European car manufacturers. These investments have stalled since the pandemic and dropped materially, so on a ten-year basis, Hungary is only slightly above average and losing ground.

Poland shows a similar, though less pronounced, picture in investment activity. Because investments are a key driver for economic growth in these countries (both lack a strong domestic consumer base, but more on that in a minute), it is entirely conceivable that the growth miracle in Hungary and Poland will soon end, and their economic growth will become more average.

If we look at inflation in the following line, we see that not all is well in these countries. While economic growth has been strong, Hungary has had the highest average inflation in the EU over the last ten years, and Poland has had very high inflation as well. This can become a significant problem if wages don’t keep up with this kind of inflation. Unfortunately, regarding real wage growth, Hungary is well below average, and Poland is roughly average for EU standards. Particularly in Hungary, that may become a significant problem because if investment growth declines, the country can only maintain high GDP growth if domestic consumption can replace investments. However, if real wage growth is sub-par, this is unlikely to happen, and the probable outcome is slowing economic growth.

Another major problem for Hungary (and to a lesser extent, Poland) is that its workers are unproductive. Labour productivity in Hungary is 26.7% below the EU average, while in Poland it is 17.3% below the EU average. At least in Poland, we see decent labour productivity growth, so the country is catching up. Nothing like that happens in Hungary, where labour productivity has stagnated for ten years under Viktor Orbán.

Finally, if we look at indicators of socioeconomic difficulty, Hungary and Poland don’t look good. The EU provides statistics for the percentage of households close to financial distress, something we call ‘just about managing’ or JAM people in the UK. Hungary and Poland rank in the top 10 countries in the EU, with the highest share of people who are just about managing.

If you take these statistics as a whole, the picture I get is that Hungary and Poland are indeed countries with strong growth, but that also have rising inequality and rising numbers of households left behind and struggling economically. The benefits of economic growth and growing wealth in the country seem to accrue to relatively few rich people and do not lift all boats. And that is the same as in many other European countries, some of which remain very liberal, some less so.