Risk aversion and loss aversion are clearly two of the most fundamental concepts in investing. People who are more loss averse and/or more risk averse tend to invest less in risky assets like equities and thus have lower retirement nest eggs later in life. Risk aversion depends on all kinds of factors like gender, income, personality, etc. but one factor has an outsized influence, yet is often ignored by practitioners: age.

I am not talking about incorporating age into an investment strategy the old-fashioned way: The older you are, the less you should invest in risky assets. I am talking about individuals’ attitudes to risk in general and losses in particular.

David Blake from City University London and his colleagues surveyed 4,000 UK citizens of all ages to identify their risk aversion and their loss aversion. To measure loss aversion, they used the old experiment of asking people about a coin flip. Heads, they lose $500, tails they win a certain amount. The amount at which individuals were willing to accept the coin toss determined the loss aversion. Going back to the famous experiments by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in the late 1970s, we know that on average, the ratio of required gains vs. losses in such a coin toss is somewhere between 2 and 3. And indeed, the average of the 4,000 British people surveyed for David Blake’s project showed a loss aversion of 2.4. All good then. Nothing to report here.

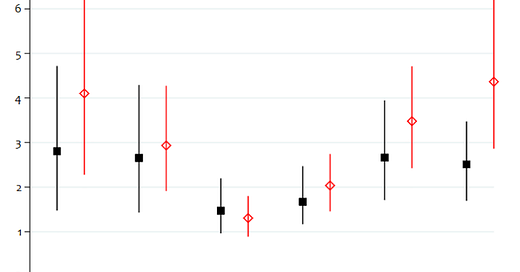

But look at the change in this loss aversion factor relative to the age of the participants. Younger people aged 18 to 24 exhibit a loss aversion coefficient somewhere between 3 and 4 as do people aged 65 and over. But people in the midst of their working lives (aged 35 to 54) tend to have much lower loss aversion, somewhere between 1 and 2.

Loss aversion coefficient across different age groups

Source: Blake et al. (2021)

Common advice for investors is to invest heavily in risk assets when they are young and then gradually reduce their risk as they grow older. But that advice goes directly against the intuition of investors. Instead, the natural inclination of younger investors is to invest more defensively, mostly because they have lower incomes and fewer savings and even small losses can have a significant impact on their financial safety. Meanwhile, as we grow older and accumulate more assets, we tend to become more risk-seeking and more willing to accept losses. It is only as we approach retirement age that we are becoming more loss averse.

I am not saying that this change in loss aversion across ages is something that advisers need to follow in their advice. The client isn’t always right, no matter what Harry Gordon Selfridge said. But advisers need to be aware when their advice goes against the natural inclination of private investors because it requires more education to get clients to accept a riskier portfolio than they would normally choose themselves. In fact, one of the great things about the study mentioned above is that it shows which traits can help reduce excessive loss aversion. Many of these traits are impossible for an adviser to influence like income, savings, or employment status. But education and financial knowledge can be influenced. And that is what advisers need to focus on to help their clients become better investors.

The concept of becoming less risky with age is in itself a flawed concept. A couple in their 60's have a 1:2 to 1:3 chance of making the mid 90's. That's 30 years away!

Making a portfolio conservative with a 30 year timeframe is a flawed thought process. No geared share investments I grant you but a 70/30 portfolio may well be needed if you want more than bread and water, especially in a low interest rate and rising inflation environment, by the time you are 90 or 95. When would such an environment happen anyway....pffff.

Of course when the client runs out of money the adviser will be well retired, I pity any clients if that's the opinion of their adviser.

FIFO: in a typical three-decade retirement, a fixed income (laden-portfolio) is a fixed outcome: penury!