2023 has been the year when people got scared about AI. Well, both enthusiastic and scared. Enthusiastic because of the endless opportunities that large language models open up to increase productivity and remove tedious work from our lives. And scared because of the possibility of AI becoming so advanced that it might soon reach the state of generalised intelligence. Generalised intelligence is not consciousness but a level of intelligence that allows the AI to analyse all kinds of complex situations autonomously and act accordingly (instead of being able to only analyse text or specific problems the AI was programmed for). In essence, reaching a state of generalised intelligence is what creates the horror scenario of the Terminator movies.

I will have more to say about a new study that tried to estimate by when AI might reach generalised intelligence next week (I don’t want to depress readers too much in one week) and focus today on the AI we already have.

In January, a study by the Brookings Institution focused on one form AI that is already in widespread use but also has significant social consequences: Surveillance technology.

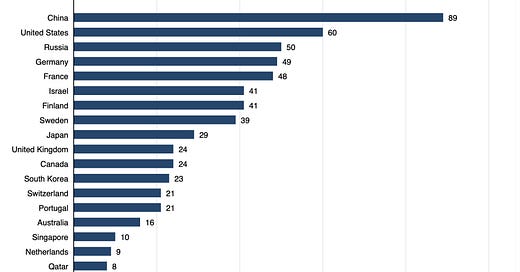

Most surveillance technology uses AI for facial recognition, predictions about the potential movements of tracked individuals and other things. The leading exporters of such surveillance technology are the United States and China, followed by Germany, Israel, and Russia. But the export patterns for countries like the United States and China differ significantly. The chart below shows in how many countries surveillance AI is exported for each country of origin. Note how China exports its surveillance technology into 89 different countries, while the US exports its tech to 60 countries.

Number of trade partners of surveillance AI for major exporters

Source: Beraja et al. (2023)

In general, democracies are exporting their technology to fewer countries than China or Russia. I think you can guess why. Most democracies know that surveillance AI is sensitive technology, and they have strict export controls that prohibit sale into authoritarian countries or countries considered ‘risky’. China doesn’t have such qualms and is willing to export its technology to anyone who is able to pay.

The study by the Brookings Institution showed that for almost all modern technologies, there is no difference in the likelihood to import Chinese tech between democracies and autocracies. The chart below shows the difference in the likelihood for a series of technologies. Negative bars indicate that well-developed democracies are slightly more likely to import this technology from China than weak democracies or autocracies. Positive bars indicate that autocracies are more likely to import the technology from China than strong democracies.

Political bias in frontier technology imports from China

Source: Beraja et al. (2023)

The only two bars that are statistically significant are the import of radioactive materials, where well-developed democracies are more likely to import from China than autocracies. Well-developed democracies have civil nuclear power programmes while most autocracies and weak democracies are subject to non-proliferation constraints and cannot legally buy radioactive material, which explains this result. The other significant result is that autocracies and weak democracies are more likely to import AI from China than well-established democracies.

Further analysis shows that autocratic regimes are more likely to purchase surveillance AI from China in the two years after an episode of civil unrest. That means that by exporting surveillance AI, China is making money. By exporting it to autocracies it is able to make more money than companies in the US can. And by exporting it to autocracies, China increases the likelihood that these autocratic regimes can remain in power and purchase more surveillance AI in the future. It’s a triple bottom line for China. They make money, ensure that the countries they sell their technology to are not being democratised and hence remain distanced from the US and other democracies politically, and they create captive buyers that will likely purchase more tech from China in the future.