Fund managers face a constant battle between two competing goals. On the one hand, we know that they generate alpha mostly with their highest conviction bets, which means that ideally, they should hold very concentrated portfolios. On the other hand, in a world of investment consultants and risk-averse investors, running highly active, highly concentrated portfolios leads to higher volatility and higher tracking error. To attract these risk-averse investors and make it past the screens of investment consultants, fund managers must hold more diversified portfolios that have fewer downside risks. Interestingly, there is one group of investment managers that is often overlooked in an analysis of the best tradeoff between generating alpha and diversifying risks: private equity managers.

Gregory Brown and his collaborators have analysed the portfolios of a large number of private equity funds and their allocation to different investments. Because private equity funds have less need to diversify their portfolios since they are not measured against a broad market benchmark, one would think that managers of private equity funds tend to hold highly concentrated portfolios where their highest conviction investments have the largest allocation. And if the fund managers have skill, then the highest conviction investments should also generate the highest returns, on average.

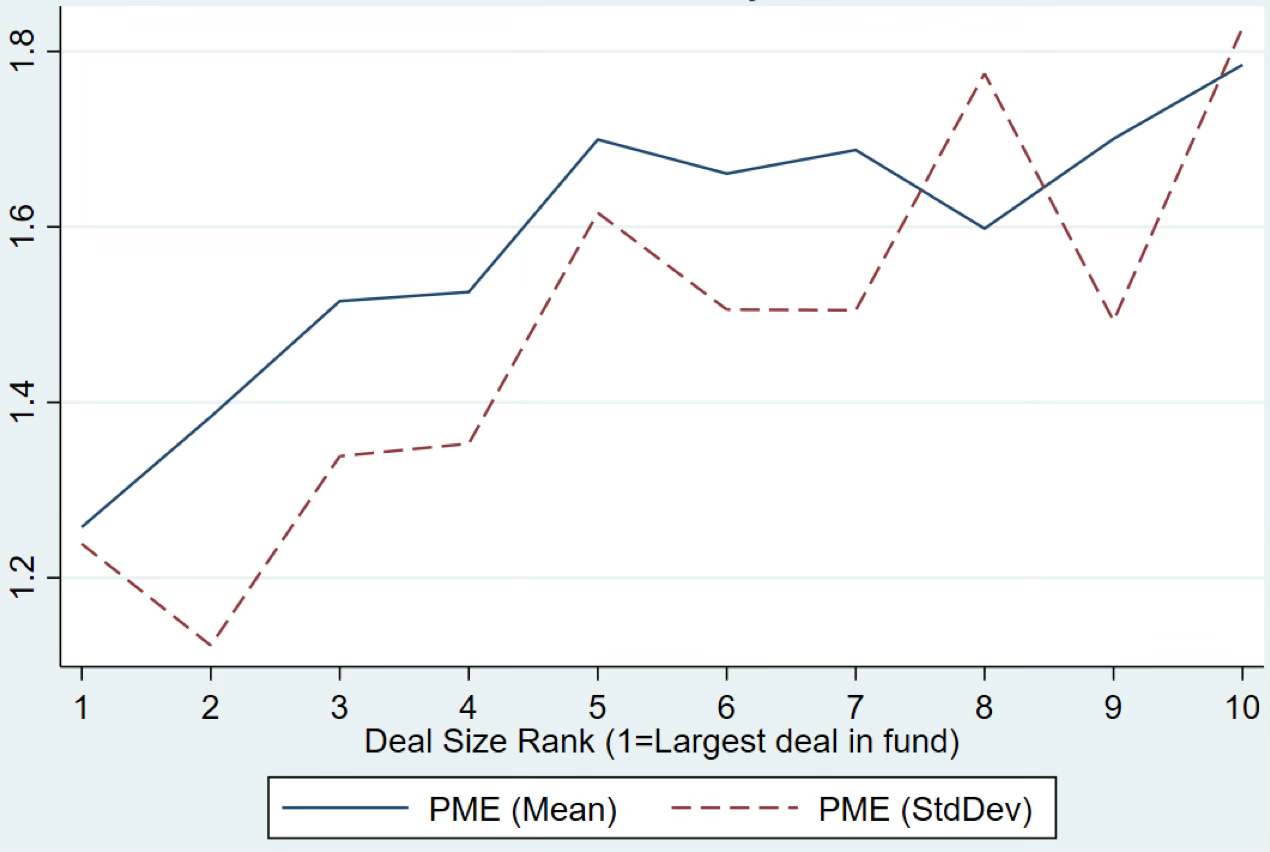

Yet, it seems the portfolios of private equity funds have very different characteristics than the portfolios of listed equity funds. For one, the largest holdings in private equity portfolios tend to be the least profitable ones while smaller holdings tend to generate most of the alpha. At the same time, the largest holdings also tend to be the least volatile ones while the alpha-generating smaller holdings tend to be the more volatile, riskier holdings.

Return and volatility of portfolio holdings by size

Source: Brown et al. (2023). Note: PME = Public market equivalent

If one looks at the order of investments made by new private equity funds it becomes clearer that the smaller holdings are likely to be the highest conviction investments since newly established private equity funds tend to invest in these high alpha, high volatility assets first and only later a dd the low-risk low alpha positions to the portfolio.

Return and volatility of portfolio holdings by order of investment

Source: Brown et al. (2023). Note: PME = Public market equivalent

I can only speculate about the motives behind this pattern, but I think two things are in play here.

First, private equity managers typically face significant size constraints in their investments. Hence, even if they have high conviction in certain assets, they simply cannot invest enough to turn these assets into their largest holdings.

Second, even though private equity funds are not measured against a broad benchmark, their performance is typically evaluated against their peers. This means that smaller, highly concentrated funds may be too risky compared to a peer group. To ensure that private equity funds can continue to raise money in the future, they have to make sure they have an acceptable risk profile, which means that in the long run, they have to add larger positions in safer, but lower-return assets.

These two drivers would also explain three important findings in the study:

Smaller, more concentrated private equity funds tend to have better performance than larger, more diversified funds. Yet, this better performance comes with a higher risk of failure and significant losses.

The skill of private equity fund managers is not expressed in the deals they invest in. The study found that only 4% of the variation in deal performance is due to manager skill while most of the variation is due to luck. In other words, looking at past deals the manager has made (e.g. being an early investor in Facebook, etc.) is a very poor indicator of skill.

The skill of private equity fund managers is more clearly expressed in their portfolio construction. While only 4% of the return of individual deals is driven by manager skill, about 40% of the return of the entire portfolio is driven by the skill of the fund manager while about 50% of the variation in portfolio returns is based on luck. This is because fund managers may have some big hits in their portfolios but if they cannot size their holdings appropriately, the losers will easily outweigh the winners and destroy the performance of the entire portfolio.

Interesting! It sounds like as if the intention of the private equity folks was to construct a kind of barbell, i.e. 80% boring yet safe stuff, and 20% high-risk and sexy investments.

Could this be a product of marketing? I mean, isn't it just another way of saying, "I won't put your equity at risk, and at the same time I am so well informed that I will make a lof of money by discovering the next big thing"?

I was also thinking about a sort of “illiquidity premium” that private equity managers could earn.