Niche consumption

Do you know what the difference between GDP and GDI is? Do you know how financial services are treated in the calculation of GDP and how this differs from other services or manufacturing? Do you know what the rental equivalent component of inflation is? Or hedonic adjustments and how they impact inflation?

If you are a professional investor and these questions baffle you, you need to learn more about the calculation of the two most influential macroeconomic variables in the world: Gross Domestic Product and Consumer Price Inflation. I am always surprised how much these two variables can move markets, yet how little they are understood by most investors.

Luckily, there is a fix for this problem. All you have to do is read Diane Coyle’s highly entertaining book “GDP – A Brief but Affectionate History”, in which she explains not only the history and details behind GDP but also the GDP deflator and inflation. The good thing is, her book is highly accessible and short, so that you can easily read it on a rainy Sunday afternoon (if your children allow you to do so).

Once you have read that, you will also understand why I get concerned when I read the new paper by Brent Neiman and Joseph Vavra on the rise of niche consumption. In it they show that over the last decade or so, households in the US have developed increasingly different consumption habits. They show how the increase in product diversity has led to different households buying more and more focused niche products. As a result, the official inflation rate as determined based on a uniform basket of products and services is becoming less and less relevant for individual households. While official inflation may be below the target of the central bank, citizens may experience everything from deflation to high inflation, depending on their consumption patterns. And as a result, monetary policy may become increasingly ineffective to manage price stability.

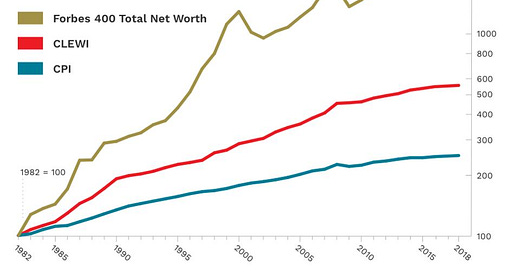

Back in the days when I worked in wealth management, we always warned wealthy individuals that their personal inflation rate can easily be half a percentage point higher than the official inflation rate. Because wealthy people buy lots of luxury goods, send their children to the best schools and universities and have access to the best health care in the world if needed, their consumption basket is geared far more towards goods and services with higher than average inflation rates. Forbes has tracked the cost of living extremely well (CLEWI) since 1976 and it shows a systematically higher inflation rate than the official numbers suggest (see chart). Luckily, that didn’t matter for most rich people too much since their wealth outpaced even this luxury inflation by a wide margin.

However, if the variation in inflation between households increases, policy makers and economists risk making the same mistake they made for many years in terms of wage inflation. Assuming that the average wage inflation was ok, they ignored differences in wage inflation between regions and households with different educational attainment for too long and thus contributed to the increase in inequality observed throughout the industrialised world. And this increase in inequality has contributed to the rise in populism and nationalism and the backlash against globalisation we have witnessed in recent years.

With the rise of niche consumption, we are now facing the risk that, as we focus more and more on different rates of wage growth for different households, we still miss an important driver of inequality. Wage growth is almost always compared to consumer price inflation to gauge if a certain group manages to improve their income or not. But if inflation rates between different groups of households start to differ widely as well, then a simple comparison of wage growth with inflation will give you a false picture. In fact, what we need is a consumer price inflation measure for the same parts of society that we measure in terms of wage growth. This would give policy makers a much better and more detailed picture of the health of the economy. In particular, it would allow to target inflation and deflationary trends not from a product perspective but from a consumer perspective, which would be incredibly helpful to create tax policies and other fiscal measures that are more effective than just a simple income tax increase or decrease. Unfortunately, none of these measures of individual inflation exist today, so we continue to steer the economy based on just one beacon of light in the middle of the ocean.

Cost of living extremely well (CLEWI) vs. consumer price inflation (CPI)

Source: Forbes.