The US election is over and it is time for me to post a rant on a topic that I have addressed with professional investors for several months now. But I didn’t want to broadcast my views before the US election was over in this forum since some readers who receive these missives might have construed them as unwelcome ‘interference’ by a foreigner. Hopefully, the temperature has cooled off now and we can talk about it with a more open mind.

In the past months, I have been in several conversations about the importance of the US Presidential election on corporate tax rates in the US. After all, if Kamala Harris is elected, that likely means that the Trump tax cuts of 2017 will not be extended and corporate tax rates revert from 21% today to the pre-2017 level of 28%.

The consensus view on this issue is that an increase in corporate tax rates will be bad for business because it reduces corporate profits. And why not? Taxes are a line item in the PnL of every company so higher taxes mean lower profits.

Alas, that is rather short-sighted, in my view. Higher taxes may be bad for some companies but good for others and on the aggregate market/index level, changing corporate tax rates is simply a redistribution of corporate profits from one group of companies to another. If that surprises you, this is the post you should read…

But before I dive into my rant today, please be aware that I am only talking about corporate tax rates, not individual tax rates like income taxes or capital gains taxes. I think their impact on economic growth and corporate profits is also commonly overestimated by investors and pundits, but I will leave that for another time.

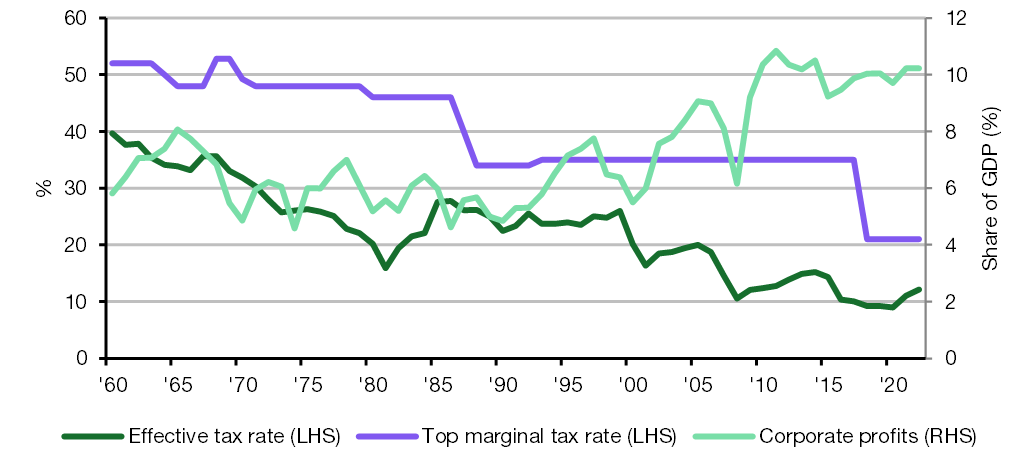

While it has become widely known that tax cuts do not create enough economic growth to compensate for the loss of revenue (and conversely, tax hikes do not cut growth enough to eliminate the increase in revenue), many investors still operate under the assumption that corporate tax cuts boost corporate profits while tax hikes reduce them. But as the chart below for the US shows, there is hardly any correlation between changes in corporate tax rates and corporate profits. Going back to the 1960s, the chart shows that corporate profits have increased predominantly during periods of stable corporate tax rates.

The correlation between changes in the top marginal corporate tax rate and corporate profits over the subsequent one to three years varies between -0.16 and -0.06. On average, a one percentage point drop in the top marginal tax rate for businesses increases corporate profits by 0.01% to 0.02% in the next one to three years.

Hardly any correlation between tax rates and corporate profits

Source: Panmure Liberum, Tax Foundation, St. Louis Fed

This non-correlation between changes in tax rates and corporate profits is surprising at first, given that taxes are a line item in the calculation of corporate profits. Reducing the tax burden directly reduces this line item and hence increases after-tax profits.

To understand why this is not the whole story, we need to dive into the Kalecki-Levy decomposition of corporate profits.

It starts with the well-known accounting identity that businesses and households can only invest what they save:

Investment = Saving

Savings can be split into the savings of the four major actors in an economy:

Saving = Corporate saving + Household Saving + Government Saving + Rest of the World (ROW) Saving

Meanwhile, corporate saving simply reflects corporate profits less dividend paid:

Corporate saving = Corporate profit – Dividends

Putting these three equations together provides the Kalecki-Levy decomposition of corporate profits:

Corporate profit = Investment + Dividends – Household saving – Government saving – ROW saving

Unfortunately, we only have the data necessary to calculate this equation in the case of the US, where the Federal Reserve’s Flow of Fund data provides all the necessary details. No such detail exists in the national accounts of the UK or other European countries.

Yet, the chart below shows that this accounting identity for corporate profits has held since the 1960s. The chart also shows some major tax cuts and two episodes of rising corporate tax rates in the last 50 years.

Kalecki-Levy decomposition of US corporate profits

Source: Panmure Liberum, Bloomberg

The Kalecki-Levy decomposition of corporate profits allows us to understand why there is no visible trend towards lower corporate profits after tax hikes or a general trend toward higher corporate profits after tax cuts (with the Bush tax cuts of 2001 the only tax cut followed by higher corporate profits).

The graphic below analyses the impact of a tax hike (e.g., expiring tax cuts from the TCJA) on corporate profits.

The mechanics of corporate tax hikes in a Kalecki-Levy framework

Source: Panmure Liberum

In a first step, higher corporate tax rates imply a direct reduction in corporate after-tax profits. However, the additional revenue generated by the government through higher taxes will be used in one of three possible ways:

The government uses part or all of the additional revenue to invest (e.g., in infrastructure). In this case, the additional tax revenues flow directly back into the economy increasing the profits of companies hired by the government (e.g., construction companies building new infrastructure).

The government uses part or all of the additional revenue to redistribute wealth. In this case, household income increases via tax credits or government support:

If this additional household income is saved, it increases the supply of capital thus reducing interest rates and allowing companies to borrow at lower costs. This, in turn, increases business investment and the profits of companies that receive these private investments.

If the additional household income is spent, consumer companies directly benefit in the form of higher profits.

If the government uses part or all of the additional revenue to reduce the deficit this reduces the supply of government debt and directly reduces the interest paid on government debt. This, in turn, means that businesses and households can borrow at lower rates and increase investment. As above, this increases corporate profits of companies that receive these investments.

What this analysis shows is that changing corporate tax rates is essentially a means to redistribute corporate profits from one group of companies to another. The net impact on corporate profits across an economy tends to be essentially zero.

This analysis also explains why there is such a significant impact on government tax revenues while the impact on economic growth is relatively small. The net impact on GDP growth from the redistribution of corporate profits depends on whether corporate profits are redirected from less efficient to more efficient areas of the economy. Shifting profits from one company to another company with the same productivity and the same utility for society leads to no change in economic growth from the changing taxation. However, if corporate profits are shifted from less productive segments of the economy to more productive ones, economic output will increase. If corporate profits are shifted from more productive segments of the economy to less productive ones, economic growth will decline.

And of course, in the process of shifting profits via government taxation, there is significant slippage that reduces the impact on GDP growth. The more direct the redistribution of corporate profits from one group of companies to another, the less slippage there will be.

Finally, before I conclude this post, I need to pre-empt a common criticism of this analysis. Of course, this analysis is only valid for moderate levels of taxation and moderate changes in corporate tax rates.

In the extreme case of a 100% corporate tax rate, all corporate profits are confiscated by the government and these effects break down, killing any incentive to invest. This is essentially what happens in communist countries.

But the analysis also breaks down at the other extreme of 0% corporate taxes. In this case, companies can keep all their profits no matter how unproductive their business ventures are. Thus, in a tax-free economy, companies are incentivised to invest in any project as long as it makes a profit, no matter how small. The result is a large-scale misallocation of capital that leads to weaker growth and higher inequality (and higher inequality leads to weaker economic growth).

I repeated the above analysis between 1947-2024 for the top marginal tax rate and corporate profit/GDP ratio, and the correlation coefficient is significantly lower.

corr(profit_gdp, taxrate) = -0,52925050

Under the null hypothesis of no correlation:

t(75) = -5,40204, with two-tailed p-value 0,0000

data source: https://tradingeconomics.com/united-states/corporate-tax-rate

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1Pik

There are poor allocations of capital at corporations and poor allocations in the government. As an investor, I can recognize poor (or good) in corporations a lot more effectively than government spending. There are certainty necessary government expenses covered by tax receipts. (how do you measure return on defense spending?) Thank you for an interesting post!