There are so many areas in life where we know we can reduce losses and avoid harm by taking preventive action, yet we wait and wait until it is too late. Think of disability insurance which costs relatively little when compared to the potential loss of income if we become temporarily or permanently disabled. Or think of medical health checks that can detect illnesses like diabetes or heart failure well before they become a serious problem yet so many people never get one of these inexpensive check-ups. Or think of investments in our portfolio that continue to underperform yet we stick with them until the losses have become so big that we cannot ignore them anymore.

When do we go to a health check or sell underperforming stocks in our portfolio? And when do we prefer to wait and hope for a turnaround or for things to not become worse than they already are?

Lijia Tan and Rob Basten have done an interesting experiment to see what drives people to take preventive measures to avoid larger losses. In their experiment, they give people the task of looking after a machine or a piece of equipment. This machine has a certain probability of failure and when it fails, the machine has to be replaced or repaired at significant costs. To avoid failure of the machine, people can take preventive measures like a refurbishment of parts of the machine which costs much less and extends the life of the machine.

In theory, the decision whether to take preventive action solely depends on two factors: how likely it is that the machine will break down in the next year and how much damage it will create once it breaks down. If you translate this into the investment world and think of underperforming assets this is the same as saying you can decide to sell an underperforming asset today and avoid further losses (plus potentially make more money by investing the money into another asset that may perform better). Or you can hold on to the underperforming asset at the risk that it keeps underperforming and you sink into an even bigger hole.

Of course, there is the possibility that performance will improve, and you get out of the hole and recover your losses, but as I discussed yesterday, sequence risk means that by holding on to an underperforming asset for a long time you are most likely never going to make up the return difference to a situation where you had sold the asset and invested it into any randomly chosen asset available at the time.

But let’s go back to the experiment I mentioned above. Assume that you have a machine where the best course of action is to take preventive measures once every four years to refurbish the machine and give it a new lease of life. In probability terms, this is as if you have a 25% probability of taking preventive measures in any given year.

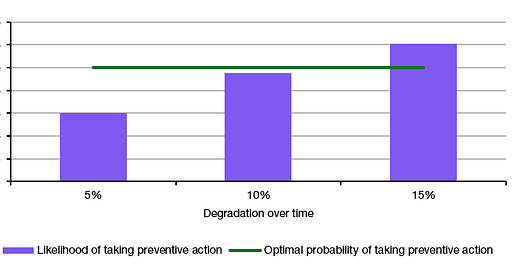

But what do people really do? The chart below shows the likelihood of people taking preventive measures as a function of how fast the machine degrades each year. Note that in theory, how fast the machine degrades should not play a role in taking preventive measures. A degrading machine can still do its job and is no more or less likely to fail than a brand new one. Instead, the degradation may influence the time it takes for the machine to produce its output or the quality of the output, etc. However, a degrading machine does not create additional costs in the form of lost revenue in this experiment.

Probability of acting on a degrading machine

Source: Tan and Basten (2023)

Yet, people react strongly to the speed of degradation of the machine rather than how likely it is to suffer a breakdown or how expensive it will be to replace a broken machine. The problem is that we cannot see, feel, or otherwise experience the probability of breaking down or the costs of repairing a broken machine. But we can directly experience the change in the machine’s look and feel, i.e. how fast it degrades. If the machine degrades only slowly each year, we don’t notice the difference and are unlikely to act. After all, the machine is as good as new after the first year and as good as last year in every year after. Of course, one day it will break down but because we acted like the proverbial frog in a slowly heated pan, we don’t jump out and boil to death.

On the other hand, if the machine degrades fast, we are much more likely to take preventive action and even do so more frequently than we need to. If we can see the degradation with our own eyes we act, if not, we do nothing.

And in my view, the same happens with underperforming assets in a portfolio. If the asset underperforms a little bit every month, quarter, or year, we are much more likely to give it another chance than if it drops 20% in one day. But by not taking preventive action on assets that underperform slowly we often rack up 20% underperformance by waiting.

Couldn't agree more. This is so true not only in investment but in other aspects of life ..our health, relationship etc.

interesting analogies and good heads-up to the referred study. That said, for retail investors, the danger of overtrading might be bigger than that of ignoring losses?