A month ago, I discussed the results of a paper that showed that the main way to reduce debt/GDP-ratios in advanced countries was not budget surpluses but a real rate of interest (r) below the real rate of growth (g), or in technical terms r-g < 0. Today, I want to dive a little deeper into that r-g component and show that without financial repression and wholesale manipulation of interest rates, we would not have the ‘low’ debt ratios we have today.

Julien Acalin and Laurence Ball looked at the US debt/GDP-ratio in the three decades after World War II from 1946 to 1975 when the country’s debt/GDP-ratio dropped from 106% to just 23%. Today, the US debt/GDP-ratio is at 102% and thus similar to the levels we have seen at the end of World War II.

As I have discussed previously, much of the debt reduction after World War II was driven by real interest rates remaining below real growth rates thanks to financial repression in the form of higher-than-expected inflation while nominal interest rates were capped, thus creating artificially low real rates.

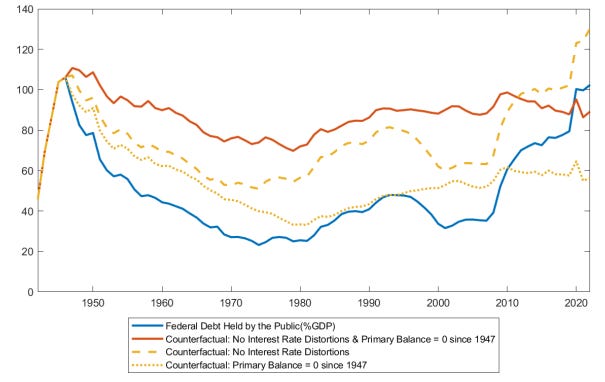

The interesting insight provided by Acalin and Ball is that they simulate the US debt/GDP-ratio under different scenarios. In one scenario, they assume that the budget is always balanced after 1947, so no deficit spending. Another scenario is one where deficits are allowed to vary as they have done historically, but interest rates are not distorted by government-imposed caps or other measures like Quantitative Easing. Finally, they simulate how US debt/GDP would have evolved had both interest rates allowed to move freely and budgets always been balanced. The chart below shows the results of these different scenarios.

US debt/GDP-ratio under different scenarios

Source: Acalin and Ball (2023)

First, let us discuss the orange line of a prudent government that follows free market doctrine, always balances its budget, and does not intervene in interest rate markets to allow bond prices to adjust freely.

Note that in this counterfactual case, the US would not have seen the same debt destruction after World War II as it really did. Instead, the US debt/GDP-ratio would have dropped only to 74%, not 23%, and then continued to increase to a level that is roughly 10% below the current debt/GDP-ratio.

If we look at the two yellow lines of counterfactual scenarios, we can understand what happened.

First, in the immediate years after World War II, much of the decline in debt was indeed driven by large budget surpluses of the government. But once you reach the 1960s, the real driver of the reduction of government debt was interest rate manipulation. From 1970 onward, the gap between the two yellow lines increases, indicating that since then, the main driver of rising debt levels has been successively larger deficits.

Without the deficits incurred by both parties in government, the US debt/GDP-ratio would be at roughly 60% today. That is great, but as I have said before, I doubt we have a realistic chance of ever getting to a world of no deficit spending.

So rather than engage in handwringing about how politicians spend money they don’t have, let’s look at the difference between the current debt level and the counterfactual without interest rate distortions (yellow dashed line). As one can see, without the Federal Reserve engaging in interest rate manipulation in the form of QE and other measures that kept long-term nominal bond yields below inflation the US debt/GDP-ratio would be somewhere around 130% right now, or roughly the same as Italy’s debt/GDP-ratio.

Financial repression by central banks since the financial crisis has reduced US debt/GDP-ratios by about a quarter! This tells you that if there is one way to reduce our large debt load, it is financial repression and artificially low long-term bond yields. If we don’t do that, our debt/GDP-ratios will simply grow too big too fast, and we end up in a global debt crisis that is much larger than anything we have seen in 2008. We need financial repression in order to survive, or as I have said in my previous article: Our future is Japan.

Excellent article which neatly avoids the question of whether governments should be allowed to spend the amounts of money which lead to levels of debt which force financial repression and favour inflation - basically robbing people to pay it down. Look no further for why house prices have grown to the point where young people cannot afford them - and that is only one of the long-term harms to the economy and quality of life

An interesting follow-up post could be on how to invest in such a world.

e.g. longer dated US TIPS with real yields of 2-3%?