On the importance of long-term earnings forecasts

I started my career in finance during the tech bubble of the late 1990s and the subsequent bust in the early 2000s. Back then, one of the hard lessons I learned was that a lot of shenanigans can be justified by assuming high long-term earnings growth. But when that earnings growth doesn’t materialise, share prices can come down a long way even though the immediate outlook for next years earnings remains the same.

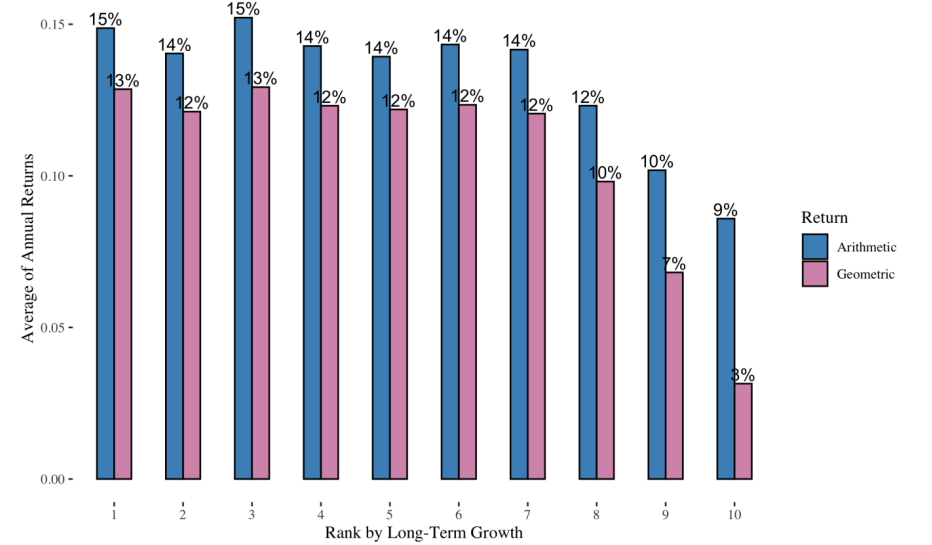

It seems in 2022 and 2023, many investors are once again learning this lesson about excessive long-term earnings assumptions the hard way. Back in 2019, I said that analysts on average price in long-term earnings growth for the company of 37.6% and explained that at this kind of expected growth would make the market cap of Amazon exceed the GDP of the US by 2050. Back then, I provided a simple way to spot companies with share prices that price in too much optimism. In essence, I said, that if you end up with a company with extremely high implied long-term growth rates you are in for disappointing returns. And if you want to know how disappointing, here is the performance of US stocks between 1981 and 2018 based on long-term growth assumptions.

Higher long-term growth assumptions lead to underperformance

Source: Hameed et al. (2022)

But by now, Amazon and other high-flying tech stocks have come down to earth in 2022, but beneath the significant decline in share prices, not all is the same. Amazon’s long-term growth expectations have declined dramatically to 3.5%. Meta’s long-term growth expectations have declined from around 20% per year in 2019 to 0.9% today. These expectations put both stocks in the bottom 30% of S&P 500 companies by growth expectations.

And then there are Tesla and Netflix. Tesla’s implied long-term earnings growth is 25% per year and for Netflix it is 23%. Both stocks are in the top 30% companies with highest earnings growth expectations despite all the bad news about competitors catching up with their business and a lack of growth opportunities in established markets. They can still outperform the market, but it is much harder for these stocks to outperform than for stocks with more pessimism priced in.

And then there is a special kind of company that (luckily, I would say) has been heading towards extinction: the conglomerate. The classic conglomerate is a company with segments operating in different segments. In a sense, the largest conglomerate in existence today is amazon, with one leg in retail and another leg in cloud computing, plus smaller training wheels in all kinds of industries. But overall, conglomerates are a thing of the past, with companies like General Electric or Danaher the exception rather than the rule.

There are all kinds of problems with conglomerates, but as a new study points out, these conglomerates are particularly prone to underperformance on the back of high long-term growth expectations.

One of the key reasons for this stronger underperformance of high growth conglomerates compared to single segment businesses is that conglomerates have the ability to manage earnings and create the illusion of stable growth, even if there is none. While different segments of a conglomerate have different cycles and thus different revenue growth over time, management can smooth earnings for each division by allocating costs away from underperforming segments and towards high-performing segments. By shifting costs from one segment to another, company management can create the illusion of a stable business that is growing steadily. This illusion, in turn can (and does as the study finds) influence analysts and the wider investor community. Stable earnings create the illusion of less uncertainty and thus warrants a higher valuation multiple. Hence, conglomerates that shift costs to smooth earnings become more overvalued and in the long run underperform more. And if I look through the S&P 500 these days, I can find among the top 20% companies with highest long-term earnings growth such conglomerates as General Electric, Danaher, and Disney.

Conglomerates are particularly vulnerable to overstated earnings growth

Source: Hameed et al. (2022)