Pay transparency done right (and wrong)

The gender pay gap is a common bugbear. Essentially, in most countries, women earn less than men even if they are doing the same or largely similar jobs. This adds to the challenge that women have when saving for retirement or trying to secure their financial future. After all, many women also work fewer years before retirement than men because they give birth to children and tend to stay home for a while to take care of them. This reduces lifetime income and sometimes career chances so career progression is also slower for women. The result is that women enter retirement typically with a 20-30% smaller nest egg than men with comparable career paths.

To reduce this gap, many developed countries have introduced laws and regulations about pay transparency. Most of these laws tend to focus on ‘horizontal pay gaps’, i.e. they create transparency about the income people in the same company at a similar level of occupation have.

This horizontal transparency is enforced in the US through salary benchmarking rules and workers’ right to talk to peers about their salaries. In most European countries, companies must report gender pay gaps by occupational group or wage ranges per occupational group.

The UK goes a step further by requiring companies to disclose not only wage gap information for employees in a firm, but also wage gaps between employees and management, so-called ‘vertical pay gaps’.

And before you complain about overregulation in the UK, let me stress that this additional transparency in the UK is a good thing.

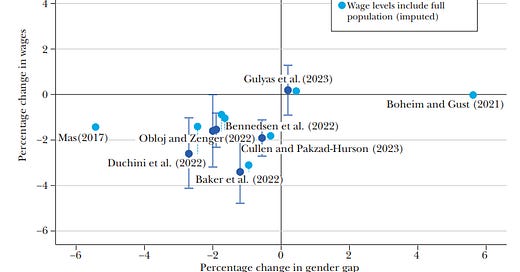

First, let’s look at the impact of horizontal wage gap transparency measures on workers’ wages. Zoe Cullen has written a wonderful overview article in the Journal of Economic Perspectives that shows that transparency on wage gaps among workers has unintended negative consequences. The chart below shows the shift in gender pay gaps and absolute wages in the aftermath of pay transparency regulation.

Impact of pay gap transparency on wages and gender pay gap

Source: Cullen (2024)

The good news is that the gender pay gap declined once it became transparent how much less women are paid in a company for doing the same job as men. Most studies find that the gender pay gap declines by about 2%.

But the unintended consequence is that wages are not levelling up but levelling down. In the aftermath of pay transparency laws, average wages in companies tend to drop by about 2%. What happens is that pay transparency among workers provides employers with added bargaining power to refuse salary increases or promotions and to hire new employees at lower wages than they otherwise would.

But there is a way to overcome these unintended consequences, and that is by introducing vertical pay gap transparency. If workers not only know how much the average co-worker at the same level makes, but also how much the average manager at every level above them, it reduces the negative effect on wages.

Sounds weird but what happens is that workers who know how much more their bosses earn become more productive. Studies show that for every 10% upward shift in the perception of the salaries of their bosses, workers worked 1.5% longer hours and increased sales revenue by 1.1%. The aspiration to get a higher income through a promotion makes people work harder and, in the end, creates additional revenue for the company that allows the firm to pay higher wages overall.

Indeed, it seems that the ultimate gold standard in terms of pay transparency is the Scandinavian system. In countries like Norway, Sweden, or Finland, some or most salaries are public, e.g. through public tax records. And studies show that this not only reduces gender pay gaps but also increases happiness in the population and improves productivity across the country. People know what their work is worth and what a fair wage is and neither they nor their employers can game the system through a lack of transparency.