Pessimists have it better

We live in a world that is awash in self-help and motivation books. You know, the kind of book that tells you that flying is easy. All you have to do is fall and miss the ground (with apologies to Douglas Adams). Personally, I blame it on the Americans with their frontier mentality and their belief that everyone can make their own luck if they just believe in it and work hard. This kind of optimism is clearly at the root of all the problems we have in the world, whether it is Brexit, climate change or Microsoft Office.

But let us take a step back and consider the two kinds of people in this world. First, there are the optimists who think the glass is half full even if there is no reason to be optimistic. For example, most people think that they are going to live longer than the average person and are going to be healthier than the average person. This is true even for the 400-pound obese person with high blood pressure and diabetes. This optimism bias is so ingrained that it has its own area of research and can be traced to specific brain regions that create this optimism bias. If you belong to this group of people, you are likely to be American, married to me or simply: normal.

And then there are the pessimists. If you are part of this tribe then congratulations, you have a realistic sense of our world and you are likely to be German, me or mildly depressed. In short, you are a superior human being.

I recently listened to an interesting episode of the BBC podcast CrowdScience on motivation. And while they made the mistake of interviewing American motivational guru Daniel Pink, it nevertheless is recommended listening since it explains a lot of the mechanisms that are at play when we try to set goals (and then regularly fail to achieve them) and evaluate our successes and failures.

One of the insights mentioned in the podcast is the fact that humans evaluate events based on a theory of relativity. Albert Einstein once apparently said:

When you sit with a pretty girl for two hours you think it’s only a minute, but when you sit on a hot stove for a minute you think it’s two hours. That’s relativity.

And this is indeed how we evaluate events in our lives as I will explain to the normal people amongst my readers now (the pessimists amongst my readers don’t need that explanation because they already know that this is true).

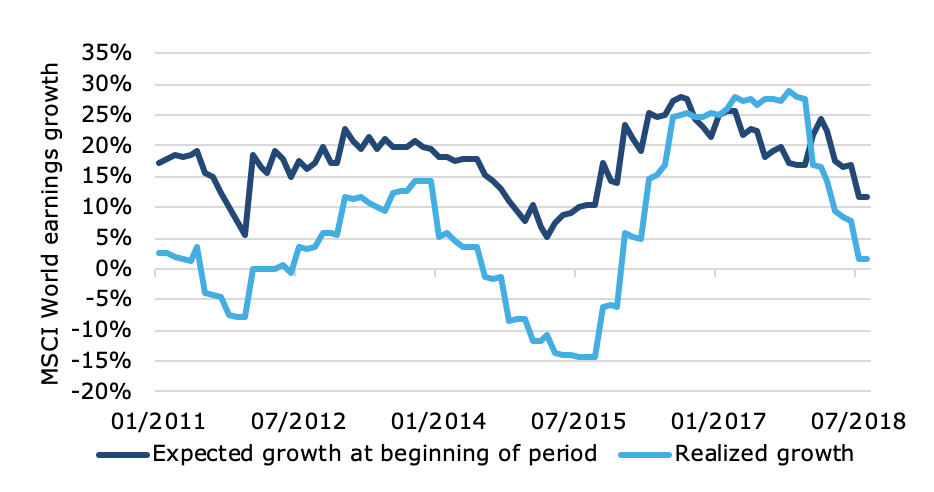

In behavioural finance, prospect theory states that we evaluate financial outcomes relative to a reference point and we suffer losses more than we value gains. As a result, stock prices react more strongly if earnings miss analyst estimates than when they beat earnings estimates. And that despite the fact that analyst earnings estimates are chronically optimistic to begin with (see chart).

MSCI World earnings growth: forecasts vs. reality

Source: Bloomberg.

Similarly, in life, pessimists have a distinct advantage due to what I call active pessimism and passive pessimism.

Active pessimism is when a pessimistic person is cautious about her own ability to achieve a specific goal. For example, you may want to lose 10 pounds, but you think you will have a hard time staying away from chocolate, cheese and other fattening food items. I would say good chocolate and good cheese are definitely worth 10 pounds body weight but let’s assume you disagree with me (in which case you’d simply be wrong). If you think you will have a hard time following the discipline of your weight-loss exercise you might put a goal of losing 5 pounds in one month and 10 pounds in six months instead of someone who is more optimistic and thinks he can lose 10 pounds in one month.

Because the pessimist set himself lower goals and split his goal into two, he now has a higher likelihood of achieving his first goal. And bang, he just got himself an achievement and a positive experience in life. This in turn is likely to motivate him to continue with his diet, which in turn enhances his chances of meeting or exceeding his final goal. And if he does, he gets a second positive experience. The optimistic person, on the other hand, tries to lose 10 pounds in one month. If he then misses this goal, he not only experiences a massive disappointment, but is likely to eat even more chocolate and cheese to drown his sorrows. In summary, the actively pessimistic person is more likely to be successful in life and has many more happy days than the optimist. Besides, the pessimist is thin and healthy, while the optimist is overweight.

In investing, the same thing happens. The pessimist tries to save 3% of his annual salary for retirement. That may be less than what most financial planners recommend, but it is a start and because the hurdle is lower, it is more likely that the pessimistic investor will be able to meet and exceed this goal. Which in turn will make it more likely that the pessimistic investor will save more for retirement in the future. This is at the heart of the very successful “save more tomorrow” concept developed by Richard Thaler and Shlomo Benartzi. Thus, the pessimistic investor not only will be healthier and happier, but also better prepared for retirement.

Then there is passive pessimism or the attitude to believe in the best of people but expect the worst. Chronic pessimists tend to think that the world is going down the drain. Passive pessimists think the world is going down the drain tomorrow. The difference is that passive pessimists expect bad things to happen, but there is still enough time to prepare oneself for it.

Think of Brexit. Passive pessimists think that a no deal Brexit can happen and that there are circumstances under which a no deal Brexit simply cannot be avoided. It is beyond one’s control. But because there is time to Brexit, passive pessimists will engage in extensive preparation for this worst-case scenario with the result that when a no deal Brexit happens, the damage is limited. Optimists, on the other hand, think that a worst-case outcome like a no deal Brexit will somehow be avoided (though they don’t quite know how) and consequently, preparations are a distraction or even worse, make this worst-case scenario more likely. If this worst-case scenario then materialises because the Conservative Party has elected a chronically overconfident and overly optimistic Prime Minister, then chaos ensues, and the fallout will be even worse.

Optimists failed to plan for the eventuality of a nationwide house price decline in the US and caused the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. Optimists think that new technologies will revolutionise the world and caused the 1990s tech bubble. Optimists think that trade wars are easy to win, and the US economy won’t enter a recession and optimists think that after Brexit, the UK will have an easy time striking trade deals with other nations.

Passive pessimists, on the other hand, know that bad things can happen from time to time. But unlike chronic pessimists they don’t expect them to be inevitable. So instead of selling all their stocks in expectation of a global trade war and depression, the passive pessimist prepares his portfolio for the possibility of a recession by selling high growth stocks in favour of more moderately priced stocks or quality stocks of companies with more reasonable growth expectations. They also invest in sectors that tend to benefit from declining long-term rates like utilities and regulated infrastructure.

If a recession comes, the passive pessimist is prepared and doesn’t have to sell things in a panic. And if things turn out better than expected, then one has another positive surprise. I for one, have never had a client who complained of getting 10% returns when they expected 5%, but I know of many investors who complained of getting 10% returns when they expected 15%.

In short, pessimists are more satisfied with their lives and their portfolios and thus more likely to stick with their investment strategy through the ups and downs of a market cycle. And this means that pessimists are going to be the better investors and will end up richer than optimists.

As I said in the title of this article, pessimists have it better.