Normally, I try to abstain from writing overly divisive notes and focus on what is going on in the world. But I suspect the series that I am embarking on will cause some people to vehemently disagree with me while others will nod their heads in agreement. So let me explain this little project first.

Coming out of a series of conversations with my wife (who is a trained philosopher though now a garden designer, but that is beyond the point) I have been thinking about the state of capitalism and economics today. Add to that a brilliant article by Paul Tucker at Engelsberg Ideas (hat tip to Simon Nixon from Wealth of Nations for pointing that out) I decided to write a series of articles on the weaknesses of modern-day capitalism and economics. While philosophical, I will try to substantiate my thoughts with data presented in previous posts or new data, I haven’t written about before.

To clear things up (and I guess I will have to repeat this disclaimer every instalment) I am a fan of capitalism, free markets, and liberal democracy. Yet, I think capitalism, free markets, and liberal democracy have their weaknesses. To make them better, we need to be able to criticise them and debate the pros and cons. Yet, every time I write something critical of free markets unbridled by any kind of government regulation or the downsides of capitalism, I get cancelled by some readers (ironically usually the same people who complain about cancel culture). If you are one of the people who thinks that all government regulation is bad no matter what or that people like Elon Musk are universal geniuses because they are successful businessmen, then you may want to skip these posts. I will put it to you that not all regulation is bad and indeed some regulation is necessary and that being successful in business doesn’t make you a genius and vice versa.

Ok, now for the real thing: Status anxiety

I have written two posts in the past inspired by Alain de Botton’s Status Anxiety. One focused on personal finance and how retail investors reduce their investment returns by comparing their investments with those of other people. The other one was broader and showed that if you tell a person that they are below average wealth compared to a peer group of similar people, they increase investment risk to ‘catch up’ with their peers. Notably, people who think they are worse off than their peers but also believe that investment outcomes are not in their own hands (i.e. they are unable to control their fate) increased risk even more.

Technology has supercharged both the feeling of being worse off than your peers and the notion of being powerless in the face of this relative decline as explained so well in Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation.

In the past, the relatively worse off tended to organise to reduce inequality and increase their welfare. The traditional form of organisation was to grab the pitchfork and march on the palaces of monarchs and the aristocracy. This kind of ‘agency’ of the disenfranchised was at least a minimal check on the power of the ruling class (rulers tended to provide famine relief and other measures to keep the masses ‘happy enough’ to prevent their heads from being pierced by a piece of metal).

In the 20th century, the pitchforks tended to be replaced by collective labour action as unions negotiated with the ruling business elite for better work conditions (which vastly increased the expected lifespan of the ruling elites, so it was a win-win).

But with the demise of the labour movement under Reagan in the US and Thatcher in the UK, the less well off have increasingly been disenfranchised. For a while that worked out ok because growth was good and people’s living standards improved thanks to the deflationary impact of globalisation and the boost to wealth from a roaring stock market and rising house prices, both fuelled in large parts by declining interest rates and globalisation.

But in 2008 that deal started to unravel. Since then we had a whole concoction of adverse trends. The financial crisis forced banks and governments to delever, creating a decline in capital available for investments and a general reduction in investments to improve productivity. Most importantly, governments increased austerity measures to reduce debt, only to find that if you stop investing in infrastructure you curb future growth. This slowdown in trend growth has been compounded by the retiring baby boomer generation which means that the labour force started to top out and eventually shrink, so growth declined even more as a larger share of the population became ‘idle’.

And as growth slowed down, governments were forced to increase tax rates to fund even the basic spending they left in place. In the UK, much of the debate about taxes in the last two years was about how the last Conservative government increased taxes to the highest level since 1948 just to be followed by a budget from the Labour government that increased taxes even more. I put it to you that if the UK had not engaged in austerity and not voluntarily abandoned free access to its largest trading partner (you know the one, if you go to the white cliffs of Dover on a clear day you can see it on the horizon) taxes would not have had to rise as much as they did.

Indeed, the Brexit vote, just like the election of Donald Trump in the US, can be understood as an act of rebellion by masses of people who are suffering from status anxiety. They saw their economic fortunes decline while the wealth of the ‘elites’ increased as they reaped the benefits from globalisation and government bailouts.

And what do people do, when they feel status anxiety and – even worse – feel like they have no control over the outcome of their actions? They increase risk. In this case, that means trying to tear the whole system down or at least give it a massive shock. They try to disrupt the status quo in the hope that what comes next will be better than what they have today.

I cannot count how many articles have been written about Donald Trump’s re-election trying to frame it as an effort to disrupt government and the status quo using the expertise of Silicon Valley tech-bros in disrupting the economy. We will see how successful that is going to be, but for now, let me state that the two major experiments with disruption in the US and UK have not been successful.

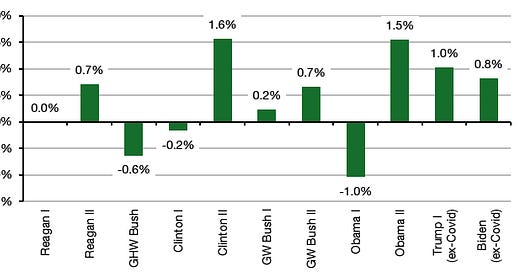

In Trump’s first term in office, the annual real wage growth for the American worker was 1.0% per year if you exclude the Covid effects and only count the results until the end of 2019. That is a strong reading but still quite a bit lower than during Obama’s second term in office. During Joe Biden’s term, annual real wage growth has been almost the same as under Trump despite the massive shock from high inflation which reduced real wages in 2022.

Real wage growth during Presidential terms

Source: Panmure Liberum, Bloomberg

More importantly, the ultimate expression of status anxiety, also known as Brexit, has been an economic failure. Before the Brexit referendum, economists warned that it would cost about 4% of UK GDP in the long run. In February of 2024 Goldman Sachs – not an organisation you would think of as in the pockets of Big Remain – estimated that in the first eight years of Brexit, the cost to the UK economy was 5% of GDP. The drivers of this economic shortfall: reduced trade, fewer investments and reduced immigration. But an increase in status for the native population and the UK as a nation. Just ask Jacob Rees-Mogg. He will tell you.

Over the next four years, the US may embark on its own experiment to counter status anxiety with the help of tariffs (to create jobs domestically and undermine Chinese competitors), reduce taxes to spur growth, and remove the threat to the status of native-born Americans by deporting illegal immigrants and reducing immigration in general. We will see how that works out but just like with Brexit, the economic ‘elites’ are warning that this will backfire.

To conclude this first instalment, let me give you an idea about how tariffs worked in the US in the past (after all, Trump likes to argue that under President McKinley tariffs were high but US growth was strong). Take a look at a new study by Alexander Klein and Christopher Meissner on the impact of tariffs during the high time of protectionism from 1870 to 1909.

They find that with higher tariffs, labour productivity on average declined in US manufacturing and more generally (quoted from their working paper):

“Our baseline results are consistent with several explanations which are not mutually incompatible. One is the idea that tariffs weakened international competition. In so doing, tariffs allowed smaller, less efficient firms to operate. Second, firms in a less competitive environment may have been less likely to invest in new products and processes.

Finally, firms and industries may have lobbied to obtain protection which could have led to an economic mis-allocation of resources.”

Change in labour productivity, value added and employment in three industries in the US during the high tariff era in the late 19th century

Source: Klein and Meissner (2024).

Imposing tariffs in 19th or early 20th century is very different from imposing it in 21st century, as american manufacturing was still in development so it is arguable that protecting the nascent industry, even if for consumers it would be bad first but good over the long run, was understandable, as this was the strategy that got england to lead the first industrial revolution and was copied by the rest of europe, and they also industrialised that way. Now that usa is the dominant force, it is bad to impose tariff because fair and open trade is great for those that already developed their industry and positioning on the global trade.

I am not nodding my head JK, I am shouting here, here. Capitalism is a wild animal. Powerful, agile, capable of great feats, but in need of a strong chain around its neck. Leave it alone and it will eat you alive without the slightest pity. Look how it was in the age of slavery. Organisation and improvements in education have reduced the exploitation of the poorer classes and now it is the turn of the unorganised, servile, middle class. Pulling its forelock before its masters is not saving it.