Looking at the ever-increasing amount of government debt across developed economies, one could be forgiven for thinking that politicians don’t care about debt sustainability, fiscal deficits, or any of that stuff. On average, they seem to prefer kicking the can down the road and running deficits today, even if that could potentially turn into a debt problem in the future. But who cares about a future when elected politicians may be out of office again?

A team from the University of Lisbon and the central bank of Latvia performed an interesting study on the responsiveness of fiscal deficits to government debt of different maturities. After all, if debt levels rise, budget deficits should decline to ensure debt remains on a trajectory where it can eventually be paid back. Debt becomes unsustainable if investors think that deficits are not going to shrink (and possibly rise) in response to an increase in debt levels. In that case, debt levels would grow exponentially at a faster and faster pace.

Looking at the debt and deficits of the 19 largest developed economies between 1995 and 2020 they found that indeed, politicians react to rising debt levels. On average a 10-percentage point increase in debt/GDP-levels leads to a reduction in the primary budget deficit of 0.3% of GDP. I know it’s not much, but it’s something. If maintained, the increase in debt would be paid back within some 30 to 40 years depending on the interest paid on the debt. The increase in debt/GDP-levels explains about one third of the change in budget deficits so clearly, politicians are paying attention to rising debt levels.

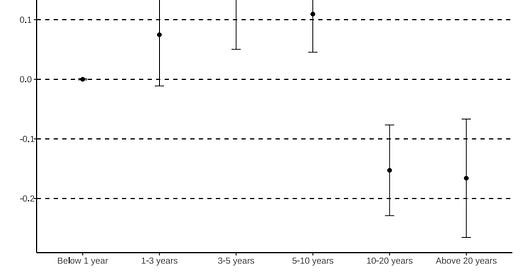

However, the responsiveness of politicians depends very much on the maturity of the debt. The chart below shows the reaction of deficits to an increase in debt levels of different maturities. Positive numbers indicate that deficits decline in response to higher debt levels while negative numbers indicate that deficits rise even if debt levels increase.

Impact of the share of debt on fiscal responsiveness

Source: Afonso et al. (2024)

Note how the responsiveness of the budget deficit peaks for debt maturities of 3 to 5 years, or roughly the length of an election cycle. If debt is rising that may come due just before the next election when you may want to increase the deficit to improve your chances of re-election, then politicians pay attention to it.

However, once the debt maturity surpasses 10 years, the reaction changes. Then higher debt levels no longer trigger declining deficits. Such long-term debt becomes a case of ‘après moi, le deluge’.

This result creates some scary numbers. If the share of government debt with a maturity of more than 10 years reaches 50%, the authors calculate that fiscal responsiveness would drop to zero for the average country. Hence, debt would become unsustainable if politicians decided to run large, unfunded deficits. For the average country in the sample, this is equivalent to an average maturity of government debt of 14 years.

Between 2000 and 2020, the average maturity of government debt increased from 5 years to 8 years, and it keeps rising. Only in the UK is the average debt maturity above this level but it has been at this level for a long time and this long maturity is sustainable in the UK due to structural differences in our bond (and pension fund) market compared to all other major economies. As long as politicians don’t blow up liability-matching strategies of pension funds with unfunded deficits, the UK government debt pile remains sustainable. Oh wait…

Share of long-term debt (left) and average maturity (right)

Source: De Graeve and Mazzolini (2023)

Well elucidated . Good read

Surely the notion that one day the debt of the US and the UK will one day be repaid is for the birds. Even I, not an economist, has realised that. It is a myth sustained by the lenders, and the borrowers only pretend to believe it because it suits them very well. In any case, even if the reckoning comes one day, it will be in the distant future, long after they have gone (to the bosom of Abraham, I hope .