This post may a bit nit-picky, but it shows how even when saving money by switching from actively managed to passive funds and ETFs, retail investors still pay too much in fees due to poor advice from brokers and wealth managers.

About a decade ago when I lived in Switzerland, I was invited by a now defunct private bank to meet a client adviser who wanted to convince me to become a client of theirs. His main sales pitch was that they just launched a portfolio mandate option that consisted only of ETFs and index funds. They said that the fee for the mandate is a mere 0.7% per year. Ok, I said, can you show me the funds you invest in? The list of ETFs were almost entirely in-house ETFs run by the company’s own portfolio management team. Fair enough. So I asked if the fees of the ETFs are included in the 0.7% fee for the mandate? It turns out they weren’t. The 0.7% fee was just for advisory and regular rebalancing of the funds. The funds themselves charged an extra 0.7% in fees.

So, I was supposed to pay 1.4% in fees for a portfolio of ETFs that were rebalanced once in a while? No thank you. I don’t pay active fees for passive performance.

That was admittedly a stark example of overpaying for something that can be bought very cheaply at other places, but a study by Ricardo Barahona from the Bank of Spain shows that something like this is still going on today. He looked at thousands of 401(k) and other defined contribution plans in the United States and the ETFs investors used to invest their retirement savings. Then he looked up the fees of the ETFs used in these pension funds for their different share classes.

We know that amongst all the ETFs that track a given index like the S&P 500 the one with the lowest fee will outperform the others. So, if you invest your retirement nest egg and you have made the decision to invest in passive funds or ETFs, just go for the cheapest one. That is what institutional investors do and as part of his study Barahona found that professional investors indeed tend to select the cheapest ETF to track a given index. They may deviate from the cheapest ETF if that one is not a physically replicating ETF and would expose the investor to counterparty risks but other than that, the name of the game is “the cheaper the better”.

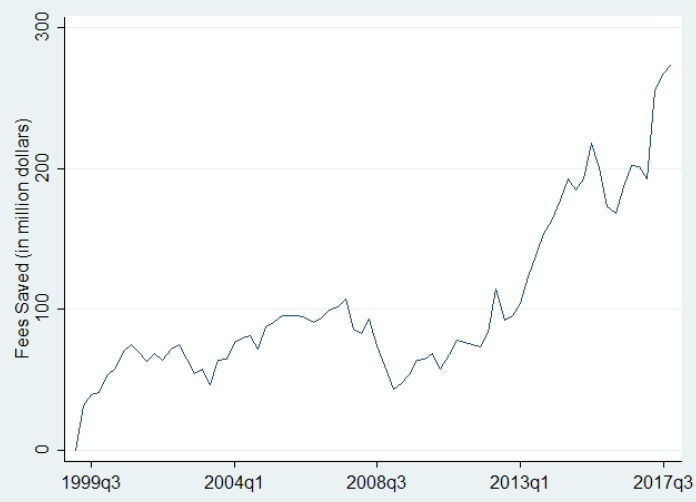

Retail investors, meanwhile, did not do that. They invested either in more expensive retail share classes of ETFs even though the 401(k) allowed them to invest in the cheaper institutional share classes. Or they invested in more expensive ETFs of other providers. The result is that between 2000 and 2017 they could have saved some $250m in fees if they had simply invested in the cheapest 20% of ETFs tracking each index.

Money lost by not investing in the cheapest 20% of ETFs for each index

Source: Barahona (2021)

In the bigger scheme of things that is not a lot of money, but Barahona investigated why retail investors were overpaying for ETFs. And it turns out that it seems largely due to advisers following their incentives and recommending retail share classes of ETFs or ETFs from specific providers (I presume their own in-house ETFs where possible). These incentives helped advisers met their sales targets but cost retail investors unnecessary fees.