Robo-advisors will grow - if they can survive long enough

Robo-advisors were all the rage about five years ago or so when upstarts like Betterment or Wealthfront became large enough competitors to traditional discretionary portfolio managers in the US. With their fully automated, low-cost offerings they were significantly cheaper than traditional bank offerings, but they also offered little to no personal advice or human interaction.

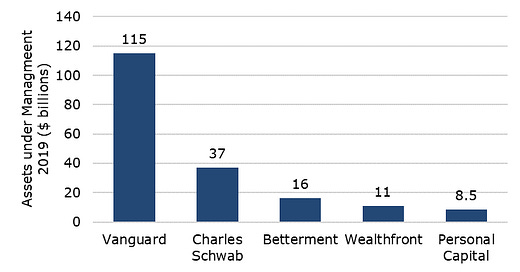

Thus, many traditional wealth managers tried to dismiss robo-advisors as a “black box” that may get some inflows from a small group of cost-sensitive investors but may not be able to grow substantially or retain clients in a downturn. Nevertheless, many banks and low-cost brokers have tried to get ahead of the curve and launched their own robo services. In some cases like UBS’ Smart Wealth this failed miserably, while in other cases it succeeded. In the US, the two largest robo-advisor platforms are the ones launched by Charles Schwab and Vanguard.

Charles Schwab managed to grow its robo-advisor platform “Schwab Intelligent Portfolios” to $37bn in assets under management by taking the fee war to its logical conclusion and offering its portfolios for zero management fee. The only fees the service earns are from the fees of Schwab’s in-house ETFs and the fees the cash holdings of the portfolios earn with Charles Schwab’s bank operations. This turns the offering of Charles Schwab into the cheapest offering overall and managed to beat Wealthfront and Betterment at their own game.

But even Schwab’s offering is dwarfed by Vanguard Personal Advisor Services which has c. $115bn in assets under management. Vanguard addressed the “black box”-argument head on and put a human advisor between the machine and the client. Thus, clients are aware that they invest in a robo-advisor but in their interactions with Vanguard they always talk to a human.

This aversion to algorithms and black boxes is often perceived as the biggest obstacle for robo-advisors but new research by Maximilian Gerber and Christoph Merkle shows that this might not be such a big obstacle after all. In their research, they asked 114 people to participate in a survey about their attitudes on robo-advisors and a laboratory experiment. During the lab experiment the participants could choose to hand their money to a human advisor or a machine. The human or the machine would then invest their money in a bond or a stock for several rounds. After a while, the participants in the experiment could choose to stay with their adviser or switch from human to machine or vice versa. The choices the participants made provided the researchers with insights if they are really averse to investing with a machine or if they lose confidence in the machine quicker than in a human advisor.

Before I summarise the research, let me state one important caveat. In my experience, younger investors are much more open to machine-based investment technologies than older ones. But at the moment, most private assets are held by elder investors (typically aged 50 or above). The laboratory experiments in this study were done with participants that were on average 22.8 years old and thus they may be skewed in favour of robo-advisors.

Nevertheless, the research found that initially, participants were about equally likely to invest with a machine as with a human portfolio manager. When surveyed about their attitudes the participants said they believed that while a human is better at aggregating qualitative information and managing extreme situations, they expected the machine to deliver higher returns than humans. This expectation of higher returns seems to drive the willingness of investors to invest in robo-advisors. Hence, unsurprisingly, investors tended to flock to robo-advisors especially after periods of strong outperformance of the robo-advisor vs. the human advisor (participants in the experiment were chasing past returns just like they do in real life). However – and this is an important warning for human wealth managers who think they will not be replaced by machines – when the robo-advisors underperformed the human advisors the participants were not switching back to human advisors at a higher rate. The rates at which investors switched from robos to humans were no different than the switches in the opposite direction when humans underperformed robos.

In short, the coming generation of investors seems perfectly happy to have their money managed by machines rather than humans. The obvious real-life test will be the next significant bear market, but for now it seems as if robo-advisors are poised to capture a larger and larger share of the private wealth management market. The biggest challenge for upstart robo-advisors does not seem to be to convince investors to fire their human advisors and trust a machine but rather to be able to survive long enough until the next generation of investors will have enough wealth to make the business of robo-advisors profitable.

The five largest robo-advisor services in the US

Source: Robo-Advisor Pros.