Sector neutral or not?

Professional investors have a knack for optimising everything. For example, while most retail investors don’t really care what kind of sector exposure they have in their stock portfolio, professionals debate whether they should be sector-neutral vs. a benchmark or not when selecting value stocks for instance.

If you follow a certain investment style like value investing you want to invest in “cheap” stocks. But what a cheap stock is depends very much on your frame of reference. A tech stock can be cheap relative to other technology stocks but expensive relative to the market overall. The result is that if you simply screen for “cheap” stocks in the market, you tend to get results with a different sector composition than the market has. The chart below, for instance looks at the 25% best stocks in the UK and then compares the resulting sector composition with the sector composition of the UK stock market. For instance, if you are a value investor and look for the 25% cheapest stocks, you will end up with a portfolio that is heavily overweight consumer discretionary, energy, financials, and real estate and underweight basic materials, consumer staples, and healthcare.

Sector deviation of different factors vs. UK equity market

Source: Liberum

That’s great at the moment when energy prices are rising and banks benefit from higher interest rates, but for the longest time over the last decade that kind of sector exposure would have held back the performance of value investors. Which is why fund managers often approach a portfolio with a sector-neutral approach in order to get rid of these sector differences that can significantly contribute to both outperformance and underperformance vs. the market.

To old-fashioned value investors that sounds like heresy because Ben Graham never cared about his sector exposure. If a company was cheap it was cheap, no matter what sector it was in. But the reality is that we live in a world of benchmarking, for better or worse, and that means that fund managers that deviate from the benchmark in unintended ways risk getting fired by their investors simply because they are straying from the benchmark too much.

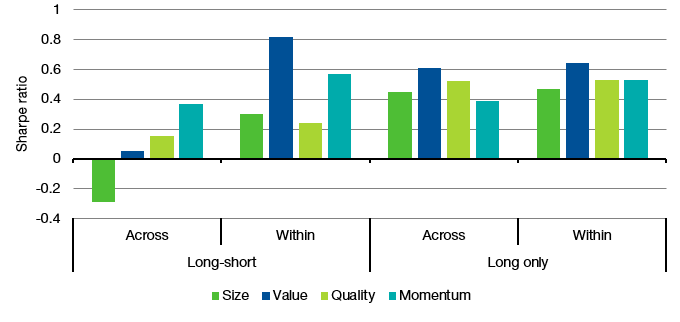

But does being sector-neutral help or hurt a portfolio’s performance? That is the question the always great Campbell Harvey and his colleagues set out to answer. And they chose a very simply and straightforward approach. They simply measured the return and volatility of a given strategy (e.g. value) in each sector and across the long and short side of the trade. Then, they essentially considered a straightforward value strategy as a portfolio of these sector-specific value strategies. Whether the combination of different sector-specific strategies yield better performance across sectors is then a matter of the risk-adjusted returns of each sector-specific strategy and the correlation between these returns.

Using data for US stocks from 1963 to 2020 their research found that in a long-short portfolio it is best to be sector-neutral because the contribution from cross-sector bets on the portfolio is much smaller than the contribution from within-sector bets. But for long only investors – and that is pretty much every traditional fund out there – their research finds that it is highly unlikely that a sector-neutral strategy will perform better than a strategy that incorporate sector bets. The reason is that in a long only environment, the contribution from cross-sector differences in valuation or other metrics is almost as high as from within-sector differences. This means that most fund managers are better off taking active sector bets and not bothering about their benchmark. Of course, that may expose them to criticism from investment consultants, but as most professionals know, these investment consultants are not good at creating returns for investors anyway.

Sharpe ratio across and within sectors for different styles

Source: Ehsani et al. (2022)