Sustainable investors shy away from some risks, especially if they feel like they are not compensated for these risks in the form of higher returns. But if an investor constantly tries to avoid some risks, the possibility arises that they reduce risk in the portfolio overall, thus hurting their long-term returns. Luckily, it seems as if this is not the case, at least not in the laboratory.

Assume you are an undergraduate student at National University in Singapore. Two professors approach you and offer you a little bit of money if you spend your time in a lab making investment decisions. Of course, you participate and when you enter the lab, your task is to allocate an investment of 100,000 tokens between three assets. The first asset (asset A) is a risk-free asset paying the prevailing interest rate (which varies between 1% and 5%). The second asset (asset B) is a risky asset paying a return of 5% above the risk-free rate but with equity-like volatility. The third one (asset C) is another risky asset that pays 5% less than the risk-free return with equity-like volatility.

But: if you invest in asset C in some cases the total return will be bumped up by 10% to reach the same expected return as for asset B. The difference is just that in one case, you the investor receives this additional return, while in two other cases the additional 10% return is donated to the Red Cross or the WWF, respectively. How did the allocation to asset C by the students change in these different payout scenarios?

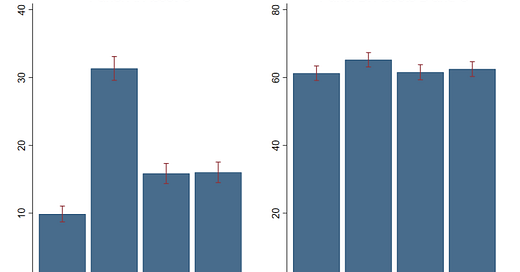

The chart below shows that the additional return in asset C increased the allocation to this asset. If asset C offers a return 5% below the risk-free rate, students on average allocated 10% of their money to it. This is not as irrational as it sounds because asset C is uncorrelated to the other risky asset B and even with the lower return, the diversification benefits can justify a small allocation to such an investment (this is, by the way, one of the reasons why it makes sense to hold commodities like gold in a portfolio even though it has equity like volatility and well-below equity-like returns).

Allocation to risky assets

Source: Chen and Chua (2022)

If asset C offered an additional 10% return, the allocation to it increased significantly. It tripled when this additional return accrued to the investor, but it also increased when the additional return did not end up with the investor but the charities. Meanwhile, the right panel in the chart below shows that the overall allocation to risky assets B and C did not change overall. Hence, given the option of allocating between a risky conventional and a risky sustainable investment, the students were perfectly happy to allocate more money from a conventional risky asset to a sustainable risky asset but overall did not reduce the risk of their portfolio.

Of course, what did happen in the experiment is that by allocating more money to asset C when 10% of the return were donated to charity the return for themselves declined. And because the allocation to asset C increased by about 5% in the case of donation to charities, we can calculate that their return expectation dropped by 0.5%. This, in turn is similar to accepting 0.5% higher management fees for a sustainable portfolio with the same return and risk expectations as a conventional portfolio. Clearly, students at Singapore National University are willing to give up returns in favour of investing sustainably, but they are not changing the riskiness of their portfolio to do so.

The two classes of investors "investors are rational" and profit seeking (think "smart money" institutions), or "investors are emotional, running on greed and fear". This study points out a third school, investors who maximize for other purposes. Charity, ESG, local businesses, etc. Thanks for pointing out this study to that third dimension.