Just before Christmas, I made myself a Christmas present and got my new Polestar 2 electric car. I always liked that car because while it is very similar to a Tesla Model 3 it is essentially a Volvo underneath, which means it has a much better build quality. But more importantly, it is a thoroughly well-designed car. Not only is it good-looking, but everything in it is properly thought through to the point where you start looking at other cars thinking to yourself: Why do they do that?

The last time I can remember having a similar experience as in this car was when I first came across Google more than 20 years ago. For those of us old enough to remember a time before Google, you might remember the interface of search engines like Altavista, Lycos, or Yahoo. Essentially, they were cluttered full of ads and links to individual sub-sections. Below is a comparison of Altavista in 1998 with the Google Beta version from the same year.

The Google revolution to search engine design

The simplicity of Google was a key differentiator. You had one search bar and that was it. And it worked. No fuzz, no distractions.

Ironically, my Polestar 2 does the same thing with the interior of a car. And it does so, by being entirely built around Google’s software platform.

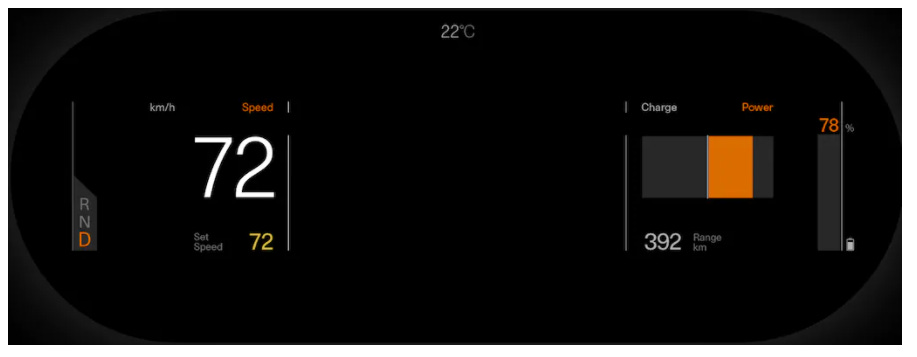

My prime example is the driver dashboard. Every car I have driven in the past had a lot of information on the dashboard. From the fuel gauge to the rev counter to the speed information, etc. And as cars become more and more like computers, more and more warning lights, indicators, and information was displayed on the dashboard.

Not so in my new car. The dashboard contains information about the speed you are going on the left together with the gear you are in (which can vary between R, D, and P, nothing else). And on the right is the battery charge level and the range. That’s it. If you put on the GPS, the middle section is filled with a little pictogram that shows you the next turn. If you really want to have more information you can display the entire Google map on the dashboard and if you set the cruise control the set speed is displayed as well, but otherwise that’s pretty much it.

The Polestar driver display

Source: Polestar

You have no idea how relaxing it is to have this kind of decluttered display. Every time I check my speed or the range while driving, I don’t have to search the info in a sea of data and indicator lights. It is right there. It may sound stupid because the time saved is maybe one or two hundredths of a second, but I can literally feel the difference. I never really noticed how my body and my brain tensed up ever so slightly when looking at the dashboard or the driver display in a car. But now, whenever I get into another car and start to drive it, I can feel how the dashboard and display stress me out – something that doesn’t happen in the Polestar and that makes driving it so much more relaxing and convenient.

Other details are similar in nature. If I turn on the indicators, they make a very different sound than indicators in other cars. It is no longer the high-pitched clack, clack of other cars, but a deeper, warmer sound that caresses your ears. Now I am actively looking forward to every opportunity I have to turn on the indicators. Somehow, the design of that sound has increased the safety of the car because I indicate more to my fellow drivers.

Ok, enough now. This is already too much praise for my new car, but the point I am getting to is that good design is design that works and makes your life easier, not something that shows off the technical prowess of the person who built it. In essence, good design follows Dieter Rams’ principles from the 1970s:

Good design is innovative

Good design makes a product useful

Good design is aesthetic

Good design makes a product understandable

Good design is unobtrusive

Good design is honest

Good design is long-lasting

Good design is thorough down to the last detail

Good design is environmentally-friendly

Good design is as little design as possible

In the financial industry, we are doing exactly the opposite when designing financial products. Actively managed funds increasingly use derivative overlays to “optimise” performance, ETFs get into ever smaller and exotic niches of the market (Millenial Consumer ETF or a Fallen Knives ETF anyone?). And don’t get me started with structured products…

Similarly, in asset allocation, we are pushing towards more and more exotic alternative investments because we expect equity and bond returns to be lower in the future than they were in the past and we are looking to diversify the dreaded risks of a bear market.

There is nothing wrong with adding alternative assets to a portfolio, but why make it more complicated than necessary?

Here is a proposal for a simple and in my view good design for a portfolio:

Decide which asset classes you want to invest in and then put an equal amount of money into each of them. Think of Harry Browne’s Permanent Portfolio which is one quarter in stocks, one quarter in long-term bonds, one quarter in short-term bonds or cash, and one quarter in gold. Personally, I like to have real estate in my portfolio as well, so I would go for 20% each in stocks, short-term bonds, long-term bonds, gold, and REITs, but that is a matter of taste.

Similarly, if you are running an equity fund, so many fund managers try to put different weights on different stocks reflecting the size of the opportunity or the conviction of the manager. Don’t do it. There is ample empirical evidence that a simple equal-weighted stock portfolio outperforms a more complex optimised portfolio in the long run. 15 years ago, Victor deMiguel and his colleagues caused a sensation when they systematically showed how much better equal-weighted portfolios are in real life than optimised portfolios. Since then, thousands of papers have been written trying to debunk or confirm these results., The verdict is still the same: Equal weight works extremely well.

When I manage equity portfolios, I use 20 or 30 stocks that I equal weight and then rebalance regularly. That’s it. And it works. But not only does it work, it removes mental load and stress from me as an investor. I don’t have to think about whether to invest a percentage point more in one stock and take a percentage point out of another stock. And I don’t have regrets if I have a stock that does much better than I thought it would and I hold it with only a small weight in my portfolio. Picking stocks and managing a portfolio is hard enough. But if you design it well, it can be much less stressful and much less work without giving up performance.

Of course, recommending such a simple well-designed portfolio to an investor will probably raise eyebrows. “If it is this simple, why do I pay you a fee in the first place? I can just as well do it myself or pay you less.” Complexity is a simple defence against fee pressure. But it is just a matter of time until your clients become wise to you and your complex gimmicks and will abandon your product for a cheaper, simpler one. Personally, my response to a clients’ question asking why she has to pay a fee for an equal-weighted portfolio is this old parable:

There was once a rich businessman with a broken beloved car. Despite several attempts, he was unable to fix the engine of that car. He called several engineers but no one was able to fix it. Finally there was an old mechanic who visited him. That old guy inspected the engine and asked for a hammer. On front side of the engine, he tapped few times with his hammer and brrroomm…brroom…It started Working! Next day, the old mechanic sent his invoice for $1000. The businessman was shocked.

He said, “ This was merely a $1 job. You just tapped the engine with your hammer. What’s there for $1000 that you are asking?”

The old mechanic said “ Let me give you a detailed invoice.”

The Invoice read:

Tapping the engine with hammer: $1

Knowing where to hit the hammer: $999

Thank you for invoking the spirit of Dieter Rams -and by extension, of his disciple Jony Ive- in connection with the art of portfolio management. Simplicity is the mark of the right stuff.

As an aside that relates more to your new Polestar than to investing: there is a thesis saying that the more complex a system becomes, the more difficult it gets to improve its performance. And the more likely it is that the system’s technology will be replace by a completely new approach.

I love my Polestar 2 as well. You’re so right about the simplicity