The economic impact of populists

Populism has been on the rise for quite a while now. Looking at the 60 largest countries in the world, a study from the Kiel Institute for the World Economy shows that in 2000, only 10% of these countries had been ruled by populist leaders from the left or right. By 2018, populism had hit a high watermark going back to 1900 with 30% of the largest countries in the world ruled by a populist leader. Then this study asked an important question: How does the economy fare under populist leaders vs. mainstream politicians?

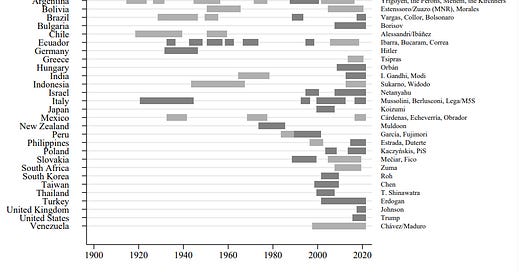

The chart below shows the 53 episodes analysed in the study where countries were ruled by a populist leader from the left or right of the spectrum.

Populist governments analysed in the study

Source: Funke et al. (2023).

Whether a politician is classified as a populist is based on the style of campaigning and the typical classification of populist politicians in political science work: A populist splits society into two artificial groups of ‘elites’ and the ‘people’ (with the dividing line between the elites and the people drawn depending on the individual circumstances in each country) and then claims to speak for ‘the people’ in their fight against ‘the elites’. Then, following the political science definition, one can differentiate between left-wing populists who fight against ‘economic elites’ (i.e. the rich) and right-wing populists who fight against foreigners and minorities and the political elites who protect them.

As the chart above shows, left-wing populists tended to be more common than right-wing populists after the Second World War and into the 1980s. In many Latin American countries (Venezuela, Argentina, Mexico), left-wing populists still hold power today. But over the last decade or so, we have seen a resurgence in right-wing populists, ranging from people like Benjamin Netanyahu in Israel, to Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey and Donald Trump in the US. In 2020, 11 out of 15 countries ruled by a populist were led by right-wing populists.

Being governed by a populist doesn’t bode well for the economy. The chart below shows what happens to GDP growth in the 15 years after a populist takes control over government compared to the growth path of similar countries. GDP growth slows down significantly for countries governed by populists compared to countries governed by mainstream politicians. The difference isn’t just a short-term one. 15 years after populists took control, countries that had populist leaders are on average 10% smaller than countries that withstood the temptation of populist politics. As the chart on the right shows, right-wing populists tend to do more economic damage on average than left-wing populists.

Real GDP path after populist governments enter office

Source: Funke et al. (2023).

To put this in numbers, 10% of lost GDP implies a loss of $2.3 trillion in output for the United States in the fifteen years after a populist took office. For the UK, it implies a loss of output of £250 billion in the fifteen years after populist politicians took control of the country.

The mechanism that drives this loss of economic growth will sound eerily familiar to observers of current affairs. The chart below shows that under populist rule, trade barriers like tariffs are increased on average, with a resulting drop in trade and a drop in financial openness and the free flow of capital.

Populist governments hurt the economy by being less open

Source: Funke et al. (2023).

But where trade declines, job creation and economic output drop as well. The results are larger government deficits and higher government indebtedness because tax receipts drop faster than the populist government is able or willing to cut spending. And because international capital flows and international trade recede, the cost of goods and services rises, creating an increase in inflation.

Populist governments typically lead to higher government indebtedness and higher inflation

Source: Funke et al. (2023).

As we have seen over the past decade or two, electing populist governments isn’t just something that happens in far-flung countries like Venezuela or Argentina. It happens to countries with some of the proudest and longest histories of democratic governance anywhere. While populist leaders claim to fight against the elites and help the people, what happens is that the people tend to suffer more under these populist leaders than under mainstream politicians, at least economically.