Populist policies and the US manufacturing slowdown

Historically, we associated populism with left-wing socialist leaders in Latin America ranging from Lula da Silva and Rousseff in Brazil to the Kirchners in Argentina and the tinpot dictators in Venezuela. They managed to get elected based on promises to help the poor with redistributional policies of their countries’ natural resources. Once elected, they often enacted programs that amounted to government handouts to the poor and the nationalisation or pseudo-nationalisation of important industries. The end result was some alleviation of poverty for a while but a lack of investments in the future that eventually came back to haunt them as revenues from the nationalised industries declined and economic growth stalled. This, in turn, led to massive government deficits and rapidly rising sovereign debt which in many cases led to runaway inflation and debt default.

Over the last five years, however, we have seen populists come to power that don’t fit that socialist paradigm. Instead, the current wave of populists are right-wing conservatives and nationalists like Donald Trump in the United States, Victor Orban in Hungary or Recep Erdogan in Turkey. These guys also promise to help the poor and the disadvantaged, but this time by promoting domestic businesses, reducing international competition or through business-friendly measures.

Donald Trump has promised to revive the manufacturing sector in the United States and enacted sweeping tax cuts for corporations and started a trade war to do so. Recep Erdogan believes that higher interest rates lead to higher inflation, so he pushes the central bank to keep interest rates as low as possible and almost caused a massive currency crisis last year.

But for economists and investors, it doesn’t really make much of a difference if the leader of a country is a left-wing or right-wing populist because their economic policies follow the same playbook and typically have the same outcome. First, you boost growth by enacting expansionary fiscal policies and/or loose monetary policies. Loose fiscal policies imply fast-rising sovereign debt which typically is not spent on investments that would provide future revenues but on increased government handouts. This means that over time, debt accumulates without any revenues to show for it. And as a result, the currency depreciates, and inflation rises. The best the populist regime can hope for is that the downturn comes after the next election or that by the time the election comes along, democratic institutions have been neutered enough so that elections don’t matter anymore.

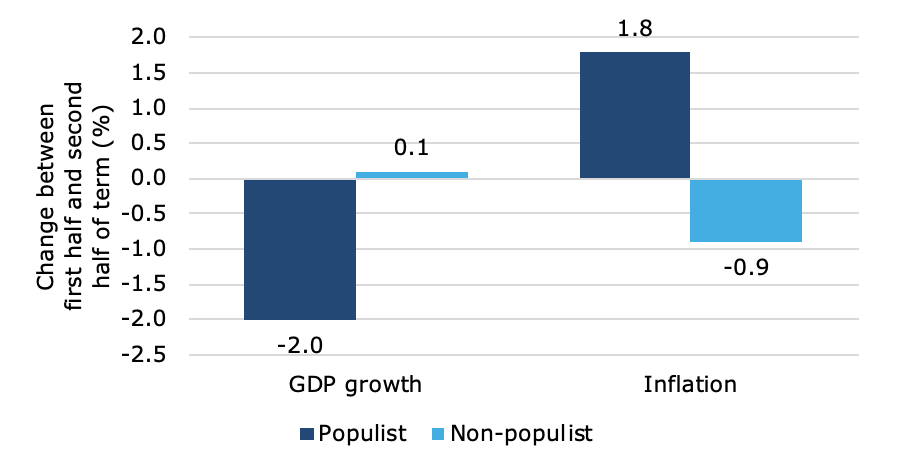

A study by Christopher Ball, Andreas Freytag, and Miriam Kautz showed that the median economic growth between the first half of the term and the second half of the term declines under populist regimes (both left-wing and right-wing) while inflation increases. In non-populist governments, on the other hand, growth remains stable throughout the term and inflation tends to fall as these non-populist governments typically enact sensible fiscal policies that don’t expand the deficit too much.

Change in median growth and inflation between the first and second half of their term in office

Source: Ball et al. (2019).

As we enter the final stretch of the first term in office of Donald Trump, it will be interesting to see if the US economy follows the same trajectory. There have already been signs of weakness in the US economy, particularly in the manufacturing sector. One of the key promises of Donald Trump was to revitalise the manufacturing sector. And thanks to the tax reform of 2018, he managed to expand the recovery of the last decade and turn it into a small boom for manufacturing workers. The number of workers increased, as did the average hours worked per week. Business was good.

But due to the tariff war with China and an overheated economy, we are now witnessing first signs of a slowdown in manufacturing. The average number of hours worked is declining while the number of employees in the manufacturing sector is starting to drop as well. The manufacturing ISM has been hovering below 50 points for several months now and on Friday, the index slipped to 47.2 points, the lowest reading since June 2009. What is worse, the new orders component dropped to a miserable 46.8 points, the lowest since April 2009, the first month after the end of the last equity bear market in the United States. It seems as if the agreement to de-escalate the trade war with China came too late in December to influence the ISM survey, but even with a boost from this agreement, the outlook for the first half of 2020 in the manufacturing sector is dire. In my view, the chart below, showing the number of people employed in the manufacturing sector and the hours worked is one of the key charts to watch this year if we want to assess the possibility of an economic slowdown and a recession in the United States. And it will play a key role in the re-election chances of Donald Trump in November. In fact, the worse the chart below gets, the more likely it will be for Donald Trump and the Republican Party to enact further fiscal stimulus or other populist measures to boost their re-election chances.

Manufacturing employment in the United States

Source: Fred St. Louis Fed.