The experience of pollution

On Friday, I wrote about the impact, pollution had on where working-class and middle-class neighbourhoods are today. As coal-fired heating and power generation increased, wealthier people moved away from the more polluted areas of a city while working-class people had to stay. But pollution has a whole host of other long-term effects.

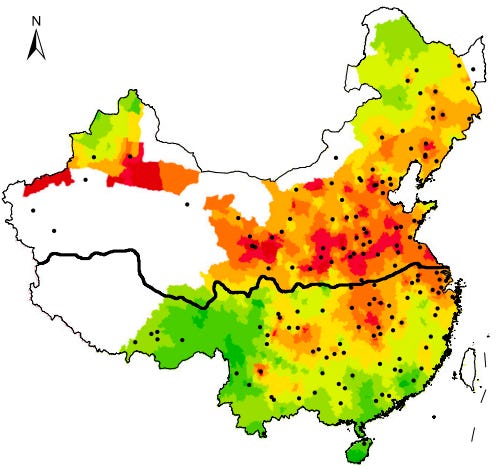

In the 1950s, the Chinese government introduced the Huai River Policy, which serves as a natural experiment on the impact of pollution on people. The goal of the policy was to ensure that people who lived north of the Huai River would have access to cheap or even free coal to heat their homes during cold winters. People who lived south of the river were presumed to have milder winters, so they didn’t get any subsidies. The result of this policy was that homes north of the river installed coal heating while homes south of the river did not. A lot of that coal heating is still active today and the chart below shows how even today, areas north of the river suffer from higher particle pollution caused by burning coal than areas south of the river.

Air pollution north and south of the river Huai

Source: Ebenstein et al. (2017). Note: Black dots indicate Disease Surveillance Points to track life expectancy and health of people.

Of course, this distinction between people north and south of the river is largely artificial, so once one controls for demographic and economic data, this policy provides a testing ground for the impact of pollution on health and other factors. For example, in a 2017 study, Avraham Ebenstein and his collaborators showed that the life expectancy of Chinese living south of the river was some 0.64 years longer than the life expectancy of Chinese living north of it.

But there are also investment implications. In 2019, Jennifer Li and her colleagues showed that Chinese living north of the river had on average a higher disposition effect than Chinese living south of it. The disposition effect is our tendency to sell winners too early and hold on to losers too long. Increased exposure to pollution is related to reduced impulse control and increased mood swings. In essence, people who are exposed to high levels of pollution have a harder time controlling themselves and that means they react more emotionally when dealing with their investments. This emotional reaction to gains and losses increases the disposition effect.

But living in a polluted environment also makes one aware of the negative consequences of emissions and should increase the emphasis on investments in companies that do not pollute the environment. A new study by Milo Bianchi and colleagues showed that first-hand experience with pollution increases investments in green stocks. Using the data from Chinese living north and south of the Huai River, they demonstrated that people living north of the river on average invested more in responsible investments. To be sure, the effect is small. A quarter percent increase in air pollution leads to a 1% increase in responsible investments but it shows that once a problem becomes tangible people change their behaviour. In the US, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was established by notable environmentalist Richard Nixon because rivers in the country were literally on fire and public pressure forced the government to do something about it. In China, the experience of pollution may not force the government to change policy, but people are increasingly voting with their wallets. And in the rest of the world, the rising impact of climate change leads to more and more people voting with their wallets as well.